A township in the green, humid centre of Kayah State is a magnet for parties and candidates looking to splurge cash on a tiny electorate in exchange for an easy win.

This article is part of Frontier’s Tale of Five Elections series. We’re following the election through five townships across the country, capturing events and local voices through the campaign, voting and declaration of winners. Stay tuned for updates about Bawlakhe, as well as Mayangone in Yangon Region, Myitkyina in Kachin State, Mrauk-U in Rakhine State and Pyawbwe in Mandalay Region.

By EI EI TOE LWIN | FRONTIER

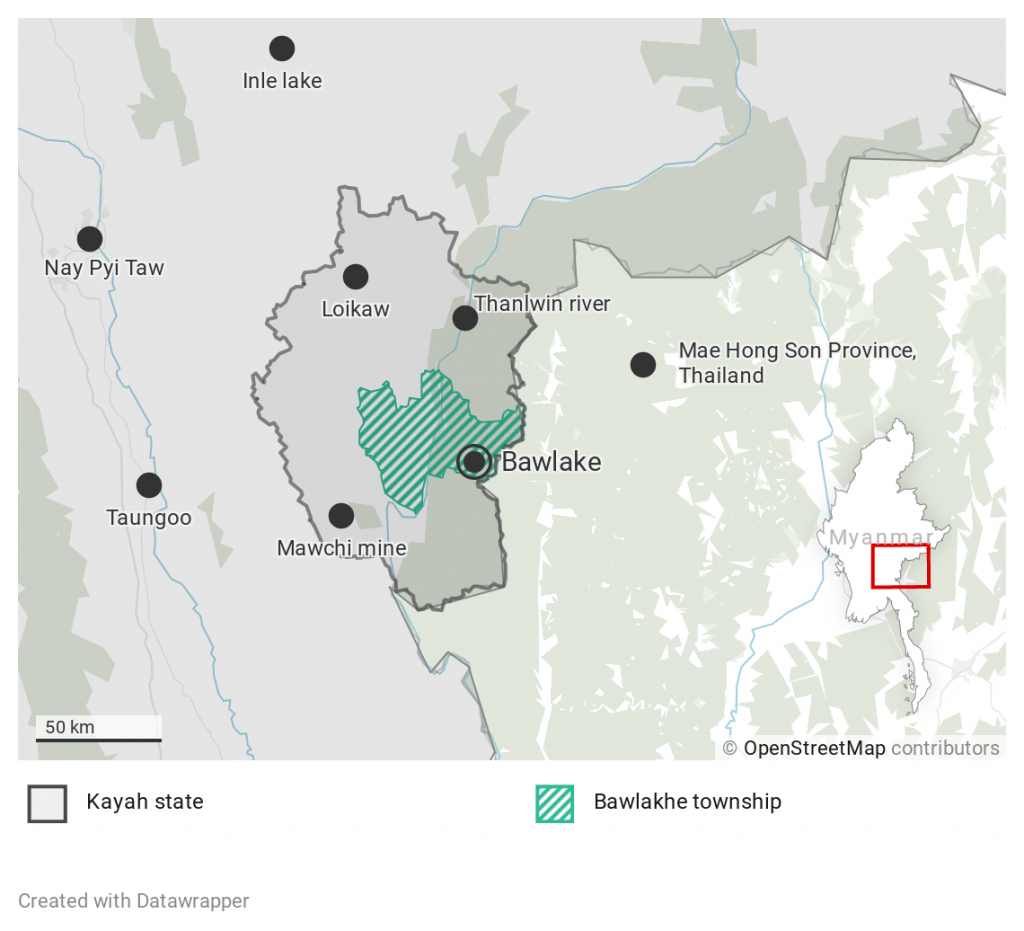

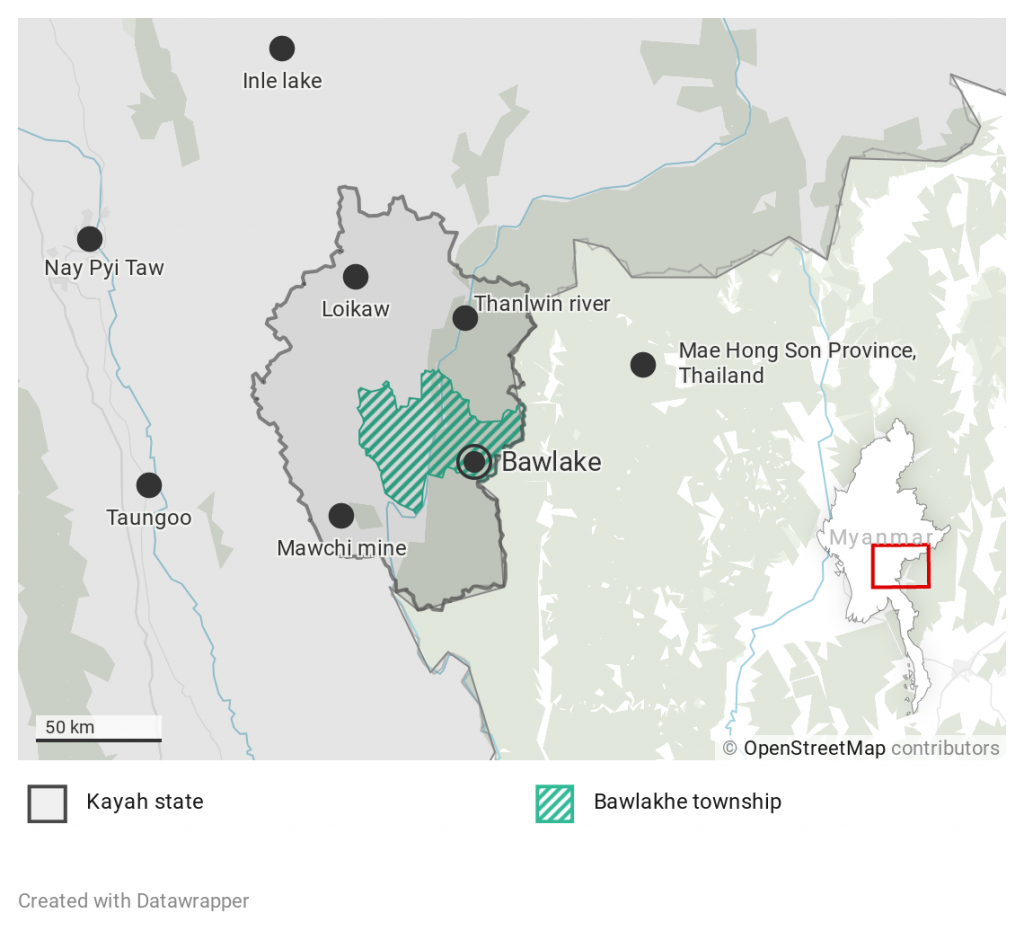

Bawlakhe Township, in a hot, low-lying valley in mountainous Kayah State, generally attracts few visitors. The overwhelmingly rural township at the centre of the state is home to about 10,000 residents, of whom more than half are ethnic Kayah. Shan are the next largest community, with a small number of other households belonging to Karen, Chin, Bamar and Rakhine families.

But as an election nears, a certain class of visitor flocks to the township: politicians.

They are drawn for a simple reason. Votes in Myanmar are not created equal, and while a ballot cast in a densely populated township of Yangon has little weight, in thinly populated Bawlakhe, a ballot is virtually weighted in gold.

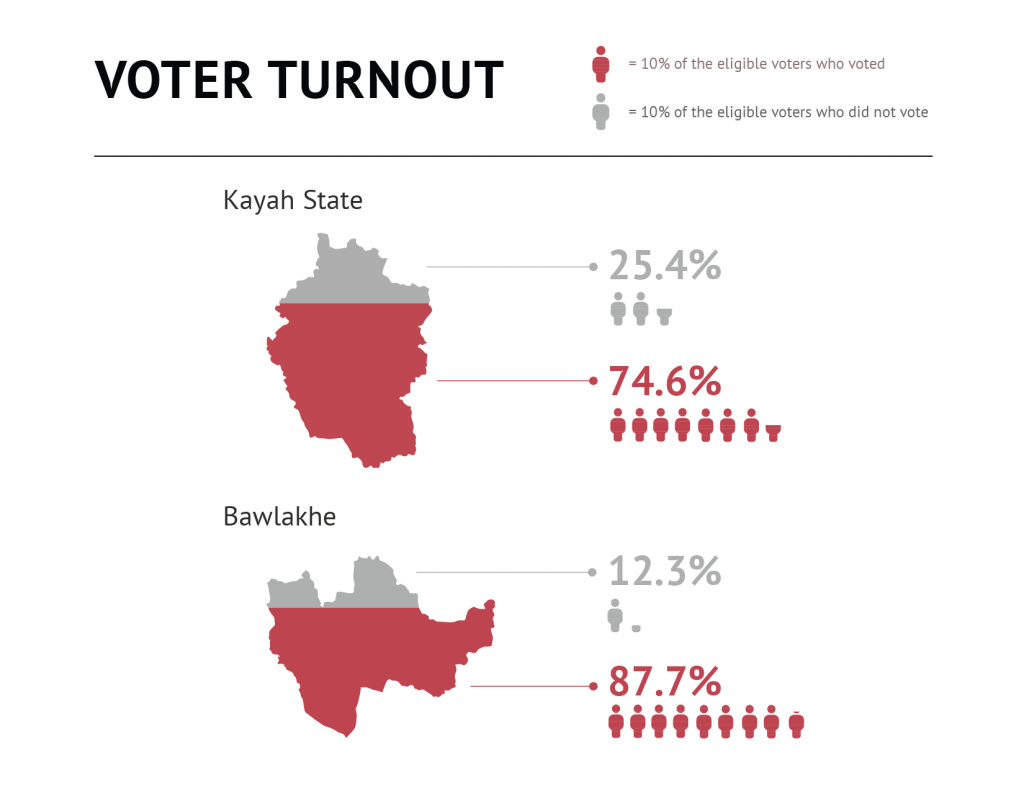

Voter constituencies are based on administrative divisions. There is one Pyithu Hluttaw, or lower house, seat for each township in the country, regardless of its size, and each township is divided into two seats in the relevant state or regional hluttaw. This creates vast discrepancies in the number of voters allocated to different constituencies – a phenomenon that election scholars call malapportionment. In electing a Pyithu Hluttaw MP, a ballot cast by one of Bawlakhe’s 8,107 eligible voters is worth about 30 times that of a voter in Yangon’s Mingaladon Township, which had 262,308 voters in 2015.

The demarcation of constituencies for the Amyotha Hluttaw boosts the influence of a Bawlakhe voter even further. Although they contain hugely varying numbers of townships, each state and region is allotted 12 upper house seats. So, while in Shan State, which has 55 townships, Amyotha Hluttaw constituencies span multiple townships, in Kayah State, which has only seven townships, most upper house constituencies span only half a township – including in Bawlakhe.

With a relatively tiny number of voters to woo, the field is predictably crowded in the run-up to the November election. Forty-one candidates from eight parties plus an independent are vying for the five seats up for grabs in Bawlakhe. This is an increase in competition from the last election in 2015, when six parties competed.

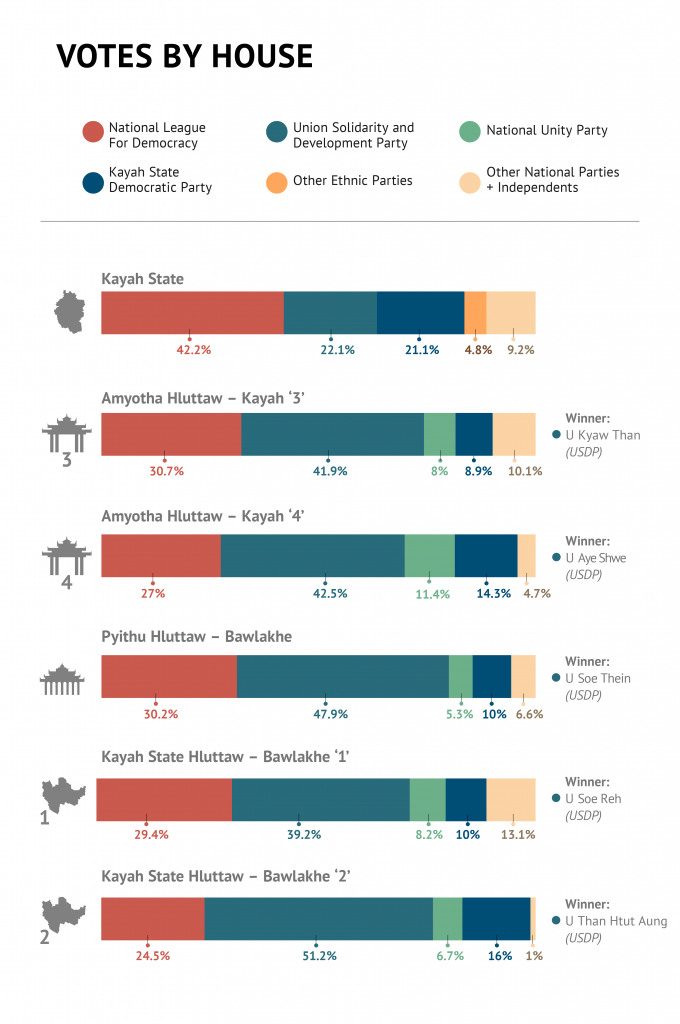

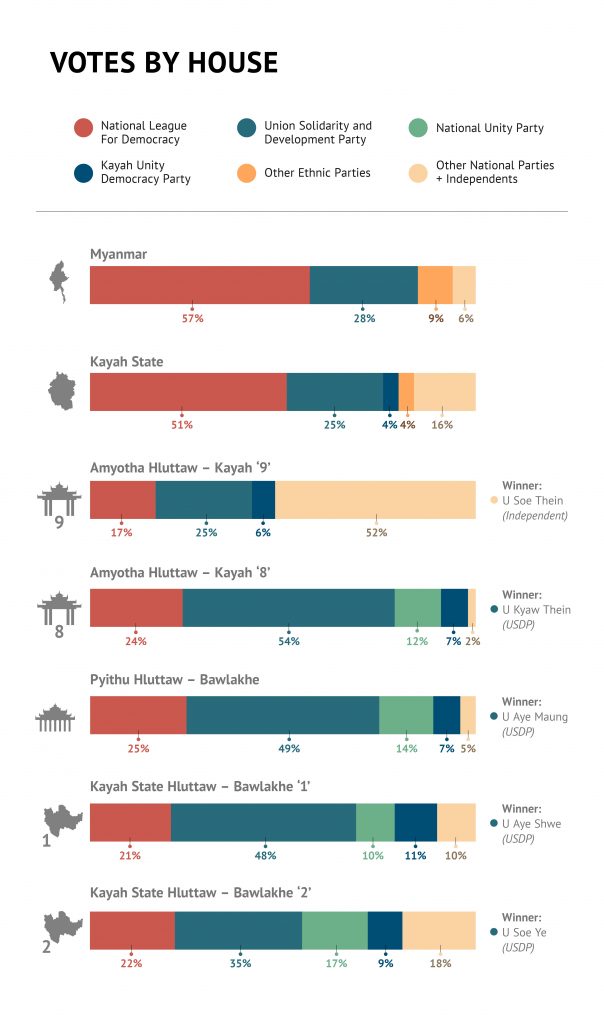

The military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party, which is the incumbent in all but one seat, will contest all races. So will the ruling National League for Democracy, which won the largest haul of seats elsewhere in Kayah in the 2015 election, and the Kayah State Democracy Party, which was formed by the merging of two Kayah-based ethnic parties and is supported by ethnic civil society activists who largely backed the NLD in 2015.

How votes were split between parties in 2015. (Source: UEC; created by Thibi)

“Political parties’ interest in standing in Bawlakhe has not diminished because they can win with a small number of votes,” said U Kyaw Lin, secretary of the election sub-commission for Bawlakhe District, which contains Bawlakhe and the townships of Mese and Hpasawng at the southern end of the state.

An additional draw, he said, is that “the situation is more stable than other areas.” He was referring to the lack of armed conflict in Bawlakhe, where the military retains tight control with three infantry battalions, supplemented by a Border Guard Force, as ethnic armed groups that come under Tatmadaw command are called.

By far the best-known incumbent in Bawlakhe is U Soe Thane, a former naval commander who was a President’s Office minister in the USDP government. Though the retired vice admiral won the Amyotha Hluttaw seat of Kayah-9 in 2015 as an independent, his lack of party affiliation was due to a factional rift within the USDP, in which he got on the wrong side of powerful parliamentary speaker U Shwe Mann. He’s returned to the USDP fold this year to contest the Pyithu Hluttaw seat in Bawlakhe.

Soe Thane is a wealthy man, and to many residents, elections are a question of how his largesse gets doled out. Residents and political parties say Soe Thane handed out mobile phones and other gifts in 2015 ahead of the official campaign period.

In addition, he used his influence as a senior minister in the USDP government to direct government funds to building roads, bridges and schools in Bawlakhe, despite having been elected to represent Kyunsu in Tanintharyi Region in the previous election. He also supported the renovation of Christian and Buddhist religious buildings and donated at least one emergency vehicle.

This patronage has returned ahead of this year’s election. A member of the Forever Hands Social Welfare Association, based in Bawlakhe, confirmed to Frontier that Soe Thane donated an ambulance worth more than K10 million in May.

Sai Lin Lin Oo, 27, is running as an NLD candidate for the USDP-held Pyithu Hluttaw seat. His toughest competition, he said, will be Soe Thane’s wallet.

“When voters hear U Soe Thane’s name, they think they will get money. It’s become a habit,” said the former Kantarawaddy Times journalist, who is a member of a legislative advisory committee to the Kayah State parliament and one of the main architects of the NLD’s social media campaign strategy across the state.

“I can’t afford to spend like him,” he said. “The only way I can [win] is to go into the community and meet as many people as possible, explaining to them that I understand their needs because I am a Bawlakhe resident. I remind them that U Soe Thane has not been here for five years to listen to the people.”

The need to maintain physical distance from voters in order to curb the spread of COVID-19 will make this intimate form of campaigning difficult. But Lin Lin Oo expects strong backing from the NLD in the form of volunteers for his campaign. It helps that his father chairs the party’s township central executive committee, of which he is also a member.

The desire for quick material rewards is heightened this year by the failure of the area’s staple sesame crop, which is planted in June and harvested from September. Locals otherwise eke out a living as daily wage labourers or run small businesses, such as the small grocery shops that line the main town, but many struggle to get by.

However, Lin Lin Oo hopes to persuade voters that well-thought-out policies for economic development will benefit them more in the long run than handouts from opportunistic politicians. “I want to create job opportunities and economic development through regional development projects,” he said. “That’s my first priority.”

Nang May Thin Kyu, who is in her second year at Loikaw University, has the same priorities. But for the 20-year-old student, that means voting in her first ever election this November for the USDP. She said her entire family will too.

“My biggest wish is to get a job after I graduate so I can support my parents. I hope the candidates I vote for create job opportunities for young people,” she said.

But U Win Maung, a 66-year-old furniture shop owner in Ywathit – a village some 40 kilometres by winding mountain road from Bawlakhe town – said most people in the township see only short-term benefits in elections.

One of the short-term benefits come in the form of party signboards. Residents who host them on their property can typically expect a one-off payment of K50,000. These signboards are now visible throughout Bawlakhe Township, including in rural areas – evidence of a pre-election economic stimulus rather than political enthusiasm.

“Most villagers are poor and uneducated,” said Win Maung, whose vote is undecided. “When government officials ask them to attend meetings about village affairs, the first thing they want to know is how much money they’ll get.”

“Most people will vote for the candidate who can give them something.”