The 21st Century Panglong conference is a symbolic step toward peace and national reconciliation, but huge challenges remain.

By OLIVER SLOW | FRONTIER

Photos STEVE TICKNER

IT’S BEEN a long time since the guns of war were silent in Myanmar.

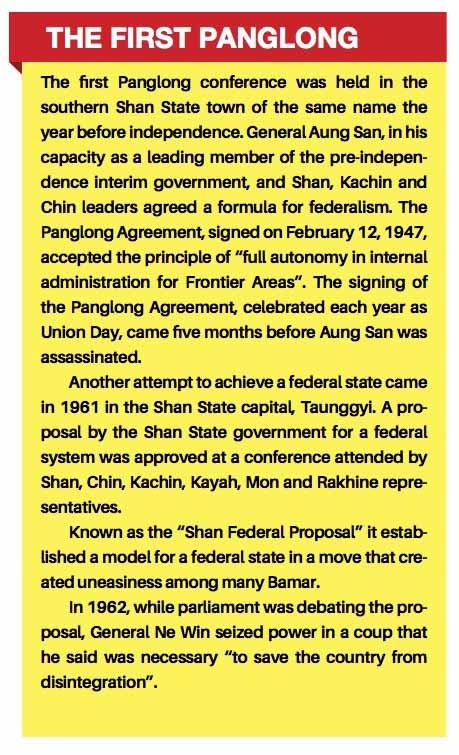

Fighting erupted within months of independence in 1948, when the Communist Party of Burma launched an armed rebellion against the government. Since then, numerous armed groups have formed, allied and splintered, leading to one of the world’s most complex and long-running civil wars.

The military coup in 1988 ushered in a period of respite. The following year, the head of Military Intelligence, Lieutenant-General Khin Nyunt, began negotiating a series of ceasefire agreements. In reality most were “gentlemen’s agreements”; one of the only formal ceasefires was signed with the Kachin Independence Organisation in February 1994.

Many of the groups that signed the agreements were allowed to keep their arms and maintain some form of territorial control. But the lack of a substantive political settlement left the process vulnerable to backsliding into conflict.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The arrival of the Thein Sein-led government in 2011 marked a new and more ambitious phase, in which a multilateral ceasefire and political negotiations were introduced.

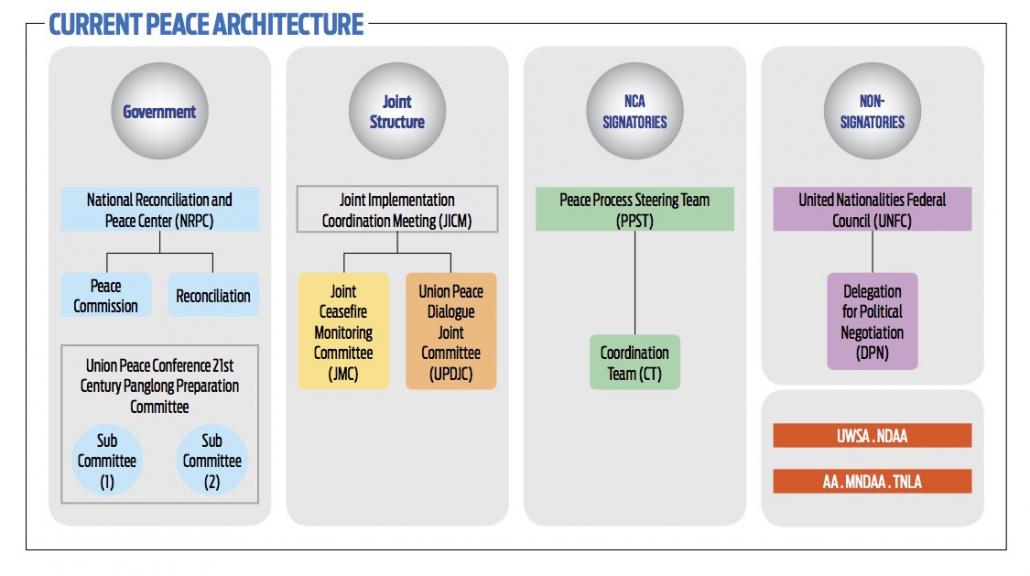

Despite facing substantial obstacles, it has achieved some success, most notably the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement signed last October by eight ethnic armed groups. While its legitimacy has been brought into question by the refusal of most leading armed groups to sign, the NCA has been retained by the National League for Democracy government as the foundation of the peace process.

State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has been a driving force behind the 21st Century Panglong Union Peace Conference, which opened in Nay Pyi Taw on August 31. She said in January that the peace process would be a major priority for her National League for Democracy government after it took office, and it would strive for an all-inclusive agreement.

A TNLA solider on a patrol nnorthern Shan State. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

At the time of going to print, most ethnic armed groups involved in the process, including signatories and non-signatories of the NCA, were expected to attend the Panglong conference. This broad participation – particularly the re-engagement of NCA non-signatories with the political dialogue process – is likely to be the most substantive outcome of the conference, according to observers.

“For a long time this event was being portrayed as the process, but now it’s very clear that it will just be an opening event,” said Mr Richard Horsey, an independent political analyst. “It’s symbolic, but symbolism is very important. There’s the symbolism of do [the groups] sign the NCA or not? That issue has nothing to do with its content, but the political context. The symbolism of [most ethnic armed groups] turning up is very important.”

Some have criticised the UPC, saying they expect it will be a “showy” event with little substance. Each group that attends will be allowed a 10-minute presentation to explain their policy positions. The format does not allow for debate or argument.

U Min Zaw Oo, a member of both the conference preparation committee and the government’s National Reconciliation and Peace Committee, said there had been “a lot of misunderstandings” about the conference’s aims.

“This is not an event, but a process. We are crossing the starting line. We have to start this process and begin negotiations,” he told Frontier.

Most of the key decisions related to the peace process will be made by groups working separately to the conference, said Min Zaw Oo.

“Whatever happens on August 31 is just the start. After that we have a series of negotiation sessions that will determine the future of the country,” he said, adding that a “second Panglong” was planned in about March next year.

Seeking inclusion

The armed groups that did not sign the NCA include two of the biggest and most influential, the KIO and the United Wa State Army. They refused to sign because the former government excluded three allied groups – the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, the Ta’ang National Liberation Army and the Arakan Army – from the peace process over their failed attempt to seize control of the Kokang region last year.

The key issue in the build-up to Panglong has been which groups will attend. The government has regularly stated that the event should be inclusive, but it also set a relatively inflexible August deadline, leaving little time for negotiations.

typeof=

The Tatmadaw has given some ground on the three groups it previously excluded from the process. Instead of requiring them to disarm, it recently said they could join the process if they gave a commitment to surrender their weapons – a seemingly symbolic gesture.

Live conflict remains an issue. The most active conflict in recent years has occurred in Kachin and northern Shan states. Late last year, fighting broke out between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw in Rakhine State, but ended in March.

“We have already agreed to the all-inclusive element and will join the 21st Century Panglong conference. What we can expect from this conference is difficult to say and depends on the decisions made there,” U Khine Tun, the Arakan Army’s head of communications, told Frontier. “We need equal rights and self-determination.”

In an April article for Brookings Institute, Min Zaw Oo outlined several ways in which the three groups could join the peace process. The AA and the Arakan Liberation Army, an NCA signatory, could merge and both work for the rights of Rakhine people; the MNDAA could disarm to join the political process in what would be “a feasible if difficult alternative considering the group’s objective to be recognised as an established armed organisation”; and the TNLA could finalise negotiations with the government that began in 2013 and sign a bilateral ceasefire.

“More generally, established and representative [ethnic armed groups] should support alternative pathways for smaller, less representative, and newer groups in order for them to participate in the peace process,” he wrote.

Min Zaw Oo told Frontier prior to the Panglong conference that he believes all ethnic armed groups now want to be part of the peace process.

But the NCA remains a stumbling block. Under the current framework, which the government is open to amending but not scrapping, only ethnic armed groups that sign the nationwide ceasefire — some non-signatories of the NCA have signed a bilateral ceasefire with the government — can take part in political negotiations, through representation on the Union Peace Joint Dialogue Committee.

Activists pray for peace at Shwedagon Pagoda. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

Those that boycotted the NCA signing last October have not yet confirmed whether they will sign the agreement. Some optimism can be drawn from the fact that nearly all have agreed upon the text of the agreement, which was negotiated over a period of two years.

Min Zaw Oo says signing the NCA will be essential for supporting the political negotiation process. The agreement includes a military code of conduct and provides for the protection of civilians and ceasefire monitoring.

“Signing the NCA will open a lot of privileges. One is the removal from the list of illegal associations and other privileges around national dialogue,” he said.

But Min Zaw Oo also cautioned that the government has to ensure “a level playing field” between armed groups. In particular, those that sign the NCA later should not be granted more privileges than the eight that signed in October 2015.

Daw Suu’s role

One of the biggest differences in the NLD government’s approach to the process has been its commitment to inclusion. The previous government, at the insistence of the Tatmadaw, did not allow the participation of the groups involved in the Kokang conflict. The inclusion of all ethnic armed groups at the 21st Century Panglong would be a step forward, as it was the major reason for the boycott of the NCA.

However, analysts said Aung San Suu Kyi will face challenges maintaining the trust of the armed groups. Additionally, her bold strategy of setting a firm date for Panglong and pushing for the inclusion of all groups could pay off in the short term, but lead to difficulties later in the process.

“By getting them there, it’s great, the process is underway, but there are difficult decisions to come. My worry is that because the groups have been sort of pushed to attend – because they recognise they don’t have any other option – they’re going to turn up, but they might be a bit grumpy about it. It may undermine some of the minimal trust that is already there,” Horsey told Frontier.

“You can’t force these groups to sign things they don’t agree with. So she has to be very careful that using her power and authority doesn’t damage the chance of certain achievements being made,” he said.

“Most of the armed groups, particularly the non-signatories, remain suspicious of her intentions. They see her position as being suspiciously aligned with the military and that worries them. They see her as Bamar first, and national leader second.”

A veteran soldier from an ethnic armed group displays his numerous war injuries. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

The government must balance its overtures to the ethnic armed groups – which are themselves divided on the peace process – with its relationship with the Tatmadaw. Although the State Counsellor is the figurehead at the top of the process, the military has the power to scupper progress if it becomes dissatisfied with the direction it takes. So far the relationship has been on a positive trajectory, but future tensions are likely as negotiations progress.

“The commander-in-chief has been very pragmatic,” said Horsey, referring to Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. “He’s agreed for her to have this symbolic event to kick-start the process.”

While the Tatmadaw’s shift of stance on the three excluded groups indicates that its positions are not set in stone, some “red lines” remain that will be difficult to redraw. They include amending the 2008 Constitution and changing the process under which groups are removed from the list of unlawful associations, a necessary step to participate in the political dialogue.

But the military also stands to gain significantly from a successful peace process.

“The commander-in-chief has always said that he wants the Tatmadaw to be a standard army; one that can stand shoulder-to-shoulder with other militaries in the region. Not only in terms of fancy equipment but in terms of their authority and respect,” Horsey said.

“If the country is going to come to see the military as a nationalistic force that people love, they’re going to need her,” he said, referring to Aung San Suu Kyi.

China and the Wa

The Panglong conference convened 10 days after Aung San Suu Kyi’s visit to China, where the peace process was among the main issues on the agenda. China has played a role in the process and was the only country with an observer at the summit of most ethnic armed groups held in July at Mai Ja Yang, a KIO stronghold. It has also pledged US$3 million to the Joint Monitoring Committee, set up under the NCA.

Although there were accusations in the past that China was preventing the peace process from moving forward, some analysts say this was a mischaracterisation of its role and interests.

“What would China benefit from an unstable Myanmar?” said Ms Yun Sun, a senior associate at the Washington-based Henry L Stimson Centre, a global security think-tank, and former China analyst for the London-based International Crisis Group.

“The business people down in southern China, the small actors, they benefit,” she said, referring to border trade. “But the Chinese government doesn’t see any direct benefits from this. If you look at the situation today, China wants to, and needs to, build a good relationship with Myanmar. So meddling in the peace process would not work in their favour.”

dsc_8118.jpg

Displaced Shan women at an IDP camp outside Wanhai, Shan State in November 2015. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

Sun believes that Beijing has encouraged the UWSA – which is widely thought to wield significant influence over some of the smaller groups operating near the Chinese border – to join the peace process. Historically the Wa have shied away from the peace process; Sun said that because they signed a bilateral ceasefire with the government in 2011 and did not see why they should be party to the NCA.

“The Wa don’t want to be independent. They want to be part of the Union, but they do want to upgrade from self-administered to becoming a recognised ethnic state.”

Accusations have been made that the Wa group has provided support, and possibly arms, to some of the non-state armies operating close to the China border.

“There’s no secret that the Wa supports these groups. They want solidarity with those groups around them, but they also know that if those other groups are eliminated, then they could be next,” Sun said, adding that the UWSA believes it has the capability to defeat the Tatmadaw if hostilities occurred in this context.

The role of the militias

An important issue that has received little attention is the role that militia will play in the process. There are hundreds of militia in Myanmar; most are aligned to the Tatmadaw, but some work with ethnic armed groups.

A July report by the Asia Foundation brought attention to the history and role of militias in Myanmar’s armed conflict.

“They have played a significant role in previous conflicts in Myanmar, and remain important actors in the country’s ongoing armed struggles. Militias themselves are not involved in discussions about key issues regarding their post-conflict role, nor has the issue of the future of militias received much attention,” the report said.

Analysts agree that it is an issue that needs to be discussed, but that now might be too early in the conversation.

“It’s one of those issues that everyone in the process recognises needs to be dealt with, but they don’t have the ability to deal with it right now,” said a specialist working on the process, who spoke to Frontier on condition of anonymity.

“It’s also a thorny topic, because anything to do with the security sector is controversial. It’s also tricky because whatever the solution to it is, whatever needs to be negotiated [involves] so many ethnic groups.”

Federalism

One of the most important demands of ethnic minorities is for the eventual creation of a federal state.

At the Mai Ja Yang summit, ethnic armed groups proposed their visions of how a federal state might look.

typeof=

Colonel Tat Zote Zarr, vice president of the ethnic Palaung TNLA, told Frontier: “We need a federal state in the future. There should be separate states for the Palaung and the Pa-O,” he said.

Resolving the multiple desires for statehood will be one of the major challenges to the entire federalism debate.

“It’s important that people have their views on it,” said Horsey. “But no one is looking at a road map, saying, ‘What are the issues? What do we want to achieve?’ Just achieving federalism isn’t the answer. That is a placemat for what comes later.”

Despite the myriad challenges the country faces to achieving peace, most analysts agree that the current process is moving in the right direction. The final destination, though, remains far from clear.

“This is a long-term process and the most likely outcome is that it won’t end with a comprehensive peace agreement,” said Horsey. “Why should Myanmar, which is so complex? Will conflict in Myanmar end in one comprehensive agreement or will it be a much messier location-specific resolution? That is much more likely, I have to say.”

Hein Ko Soe contributed to this report.