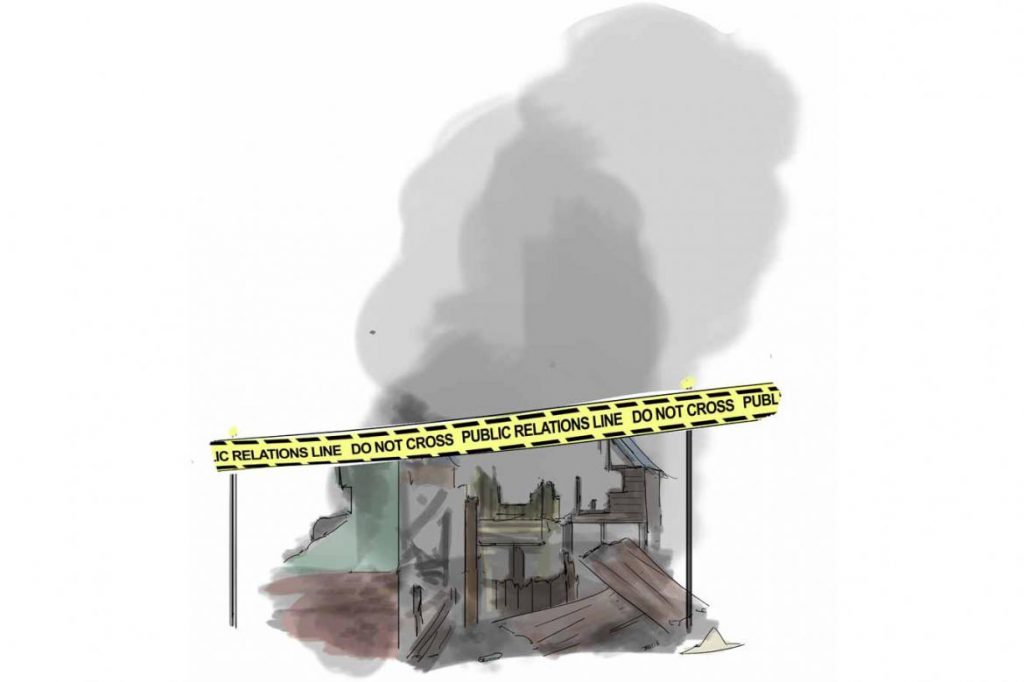

When it comes to recent events in Rakhine State, nobody has a monopoly on the truth.

ON NOVEMBER 16, the government called a press conference to respond to allegations that hundreds buildings in Muslim villages had been burned in northern Rakhine State. Spokesman U Zaw Htay then proceeded to present evidence in an effort to refute allegations made recently by Human Rights Watch. Not only were the allegations inaccurate, he said, the New York-based rights group had “lost touch with reality”.

Using satellite imagery, Human Rights Watch had estimated that 430 buildings had been destroyed in three villages. Zaw Htay said that after checking with helicopters and ground-based teams, the government had found that only 155 houses had been burned.

With this, Zaw Htay insisted the matter was settled. The government had presented the “real situation” and “wrong accusations” had been refuted. This found a receptive audience online, where it was held up as just more evidence of “biased” foreign media and NGOs.

But let’s imagine for a minute the allegations were instead that homes had been burned in Kachin State, Shan State or Kayin State. Would this rebuttal have been accepted so swiftly and easily? It seems very unlikely.

One also hopes that in those regions of the country reports of rape would also not be laughed off as impossible (on the grounds that the alleged victims are “very dirty”, no less) by the head of a parliament-appointed investigation team.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

No doubt U Aung Win, the Arakan National Party MP leading the investigation who made the comments to the BBC, was just reflecting the views of many of his constituents.

Because the real bias here seems to be not so much among international media, but a confirmation bias on the part of many people in Myanmar. Government or military denials of rights abuses tend to be viewed with suspicion – and rightly so, given the military’s long history of disinformation and propaganda.

But when those denials are made in the context of Rakhine State, they are held up as the incontrovertible truth. People, it seems, will believe what they want to believe.

That’s not to say that Frontier believes every allegation of human rights abuses in Rakhine State that is being levelled. Quite the contrary, in fact: Unless we can verify the allegation, we consider it just that – and certainly not a fact.

But at the same time, we are unable to verify that what Zaw Htay said on November 16 on behalf of the government is accurate. As a result, we will treat his comments with the scepticism that they deserve. This is a basic tenet of responsible journalism.

It’s unfortunate that the new State Counsellor’s Office information committee, of which Zaw Htay is secretary, didn’t read the Human Rights Watch report more closely, though.

For example, at no point did Human Rights Watch accuse the military of burning the buildings. But the Global New Light of Myanmar report said the information committee “refuted a recent report by [Human Rights Watch] that accused Tatmadaw troops of burning down houses in northern Rakhine State”.

While the Human Rights Watch report also made no mention of Dargyizar village, at the press conference Zaw Htay said the rights group had alleged that all 700 buildings in the village had been burned down.

(In a subsequent report, released on November 21, Human Rights Watch said that an analysis of new satellite imagery had found that 265 buildings in Dargyizar had been burned.)

The November 13 Human Rights Watch report noted only that “buildings” appeared to have been burned, while the information committee referred to “houses”.

Forgive us, then, if we don’t take everything this new information committee – or the government, or military, or anyone for that matter – says at face value. No one has a monopoly on the truth.

But this recent focus on details obscures, perhaps deliberately, the real issue here: that an investigation is needed to assess allegations of human rights abuses.

The government itself has admitted that more than 150 homes have been burned in a handful of villages. Additionally, while the military rejected reports it had killed 80 people in Dargyizar village on November 12, it has said that it fired on a crowd of 800 armed attackers from a helicopter, killing at least 25 people.

Even if the lower figures are accurate, this still represents a substantial loss of life and property.

A credible and independent investigation is needed – and that’s something that the government alone cannot deliver.

This editorial originally appeared in the November 24 edition of Frontier.