Kan Htoo Aung has been disabled from birth but an indefatigable spirit has enabled him to overcome his handicap and devote his life to helping others.

By SU MYAT MON | FRONTIER

“‘IMPOSSIBLE’ is not a word I use; I’d rather say ‘not yet’,” a smiling Ko Kan Htoo Aung said as he sat in a wheelchair outside his family home in Upper Kanni village in Mon State’s Kyaikto Township.

Family support, determination and a positive attitude have enabled Kan Htoo Aung, 31, to shrug off the disability he was born with and devote his life to helping others in his role as a provider of medical care to his community.

Kan Htoo Aung finds motivation in the possible and his approach to life is summed up in a saying he likes to recite: “Whether someone is disabled or not, what’s most important is their capability.”

His daily routine begins with administering medication to patients at the clinic in his house before heading out on home visits. To conduct these visits, someone from the community will carry Kan Htoo Aung out of his house on their back, prop him on a motorbike and drive him to the patient’s house.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Kan Htoo Aung is devoted to his work and provides care whenever patients call, regardless of the time of day.

“He was the only one born with a disability, so we named him Kan Htoo Aung,” said his mother, Daw Sein May, 63, who has been a pillar of support for her son. Kan Htoo Aung means “lucky”.

Kan Htoo Aung was born without the ability to use his legs but was a well-spoken, confident boy whose character displayed persistence and determination, Sein Mya said.

She recalled incidents when Kan Htoo Aung wanted to leave the house, but his brothers would not help him, even when he offered them money.

“But as his upper body was good, he could use his hands to pull himself down the staircase by the handrail and get outside,” said Sein Mya.

He attended high school but was unable to complete his studies because of a limited family budget and transport difficulties. The school was 3 miles (4.8 kilometres) from home and getting there involved balancing precariously on bicycles ridden by friends.

“It was not like today; there were no buses or motorbikes to travel to school, otherwise I could have finished high school,” Kan Htoo Aung said.

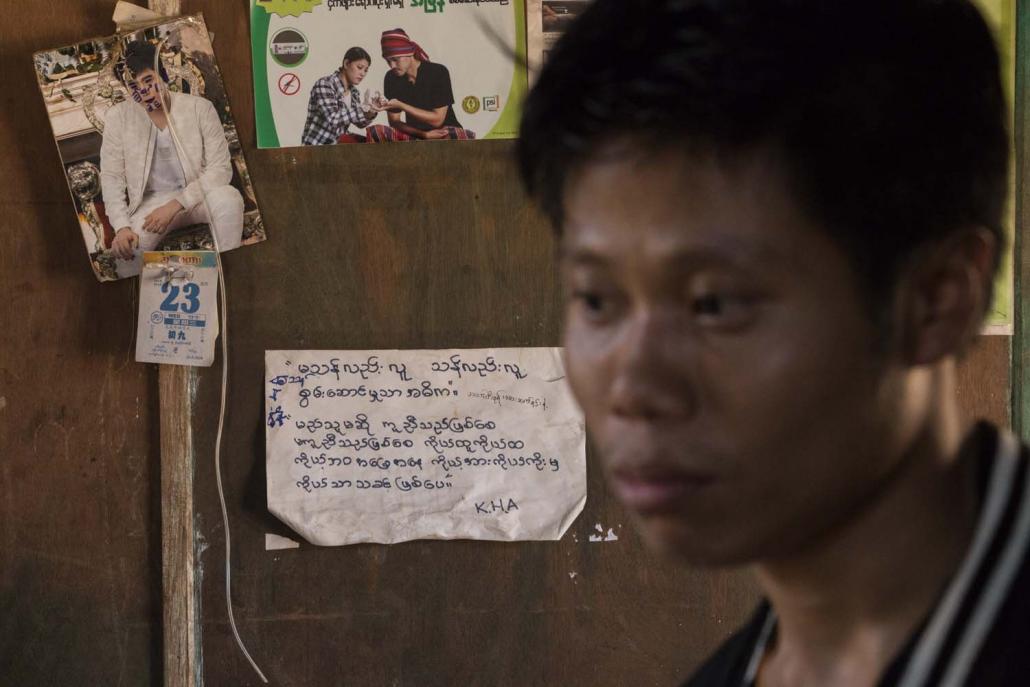

A handwritten note in Ko Kan Htoo Aung’s home says, ‘whether we are disabled or not, we are all human’. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

He said that because of the influence of his father, a Tatmadaw army medic named U Ye Naing, medical care had been his main interest since childhood, followed by using computers.

In 2002, he began helping his father provide treatment to residents in Upper Kanni, which is about 18 miles (30 km) from Kyaikto town, and in 2009 – three years after his father passed away – he began working independently to help the community.

He has undertaken a course in public health in Yangon and also received training from Washington-based health care NGO, Population Services International, after he began working on its malaria eradication project two years ago. He’s one of more than 150 people in Mon State providing artemisinin monotherapy replacement in their communities as part of the project.

Asked why he wanted to become a medical provider, Kan Htoo Aung said: “Instead of sitting in a wheelchair for the rest of my life, I wanted to help others.”

Kan Htoo Aung said he acquired considerable practical knowledge from observing his father treat patients and also helped by maintaining their medical records.

He also helped as an assistant when staff from the township medical department visited the village.

When Kanni village residents fall ill, they often turn to Ko Kan Htoo Aung for treatment. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

But his altruism was not always appreciated. When he was trying to become a medical provider, some people – underestimating his determination and ability – said a person with a disability could not fill the role.

“But now, I am able to save the lives of able-bodied people,” he said proudly.

That doesn’t mean it’s always an easy job for Kan Htoo Aung. One of the main challenges he faces is arranging house visits.

“I have to rely on others and I need someone to take me on a motorbike to the patient’s house,” he said. If no one is available to help it means a delay in providing medication.

“Arranging transportation is the hardest part of my work,” Kan Htoo Aung said. “If a patient is so seriously ill that they cannot come to me and if I am unable to arrange transport to see them, it’s difficult for them to get referred to the hospital.”

A self-powered wheelchair that eliminated the need to rely on others for transport “would be great”, he said.

“I have considered buying one, but I can’t afford it now and will have to wait.”

Many of the rural people Kan Htoo Aung treats are poor and sometimes he provides free care.

“Money is scarce for some patients and if you treat them for free with sincere goodwill, your karma will be good; I believe that as a Buddhist,” he said.

A man carries Ko Kan Htoo Aung to a motorbike so he can visit a patient. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

The main health problems in the area in the past were malaria, dengue fever, seasonal influenza and diarrhoea but the incidence of these ailments has declined, Kan Htoo Aung said, and fatal cases of these diseases are now rare.

“The government comes once a year, but they only spray [insecticide] at the school,” he told Frontier. “Maybe that’s why there’s so many mosquitoes,” he added, laughing.

Kan Htoo Aung said he wished the government would conduct more effective national campaigns to raise public awareness about disease prevention. In particular, he said, medical staff should spend more time visiting communities. “When the government does nothing about public health in rural areas, residents have to rely on people like me.”

Among those in the village who rely on Kan Htoo Aung is Daw San San Maw, 42, who has cancer of the stomach and is in serious pain. He regularly visits her at home to give injections to help reduce her suffering.

“He might be disabled, but he is like a superman for us,” said her sister, Daw San San Aye, 48.

Kan Htoo Aung said he always encourages the disabled people he meets to overcome any shyness they may have about their appearance.

He welcomed changing attitudes towards the disabled, who were once regarded as a burden but have enjoyed increasing acceptance by demonstrating that they can use their ability to contribute to their communities.

More opportunities need to be provided for the disabled so they can acquire the skills needed to be self-sufficient and they also need more support from the government, he added.

Family support is also important. Referring to the encouragement given by his mother, Kan Htoo Aung said, “Without support from their family, it’s difficult for a disabled person to achieve anything.”