Hundreds of people live as squatters on a sliver of riverside land along the Myanmar-Thai border that is notorious for lawlessness and drug deals.

Words & Photos BRENNAN O’CONNOR | FRONTIER

WEDGED BETWEEN Myawaddy in Kayin State and the Thai town of Mae Sot is a large squatters’ community known as “No Man’s Land” by locals, because neither Thailand nor Myanmar show much interest in exerting control over the area.

Covering about 1.6 hectares along the border with Thailand, No Man’s Land is a narrow strip of territory on the Moei River that is home to several hundred Myanmar people who, due mainly to poverty, have found themselves living on the margins of the two countries.

Residents of nearby villages call the area No Man’s Land in English. In Myanmar it is called yei le kyun, which means “The island on the middle river”. It is one of several such locations along the border where residents, who are mainly from Myanmar, are victims of corruption, exploitation and poverty.

A merchant from “No Man’s Land” sells cigarettes to a Thai man standing on the boundaries of the official Thai border. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Most of the residents of No Man’s Land support themselves as mobile food vendors, selling Myanmar and Chinese cigarettes to Thais and foreign tourists, collecting recyclables and begging.

The other main economic activity are the drug deals that have made No Man’s Land notorious for lawlessness, especially after dark when the Thai soldiers who monitor the area have returned to base.

Some nearby residents say a Myanmar Border Guard Force profits from the illicit activities at No Man’s Land. Others say both Thai and Myanmar police receive bribes to ignore the drug deals and other crime.

Although both Thailand and Myanmar claim jurisdiction over No Man’s Land, it is rare for Thai police to set foot in the area.

Migrant workers from Myanmar queue up to receive travel and work documents on the Thai side of the Friendship Bridge that connects the two countries

Myanmar sends police across the river every dry season to burn back the jungle around the squatting community. Somehow, the squatters know in advance when this will happen and they relocate temporarily and return after the burn-off is finished.

Evidence has emerged recently that the official non-involvement of Thai police in No Man’s Land may be changing.

A migrant worker who requested anonymity has told Frontier of seeing a joint Thai-Myanmar police raid on No Man’s Land in September that lasted several hours.

The worker, who lives in Mae Sot, saw the raid while returning to Thailand at one of the unofficial border crossing points on the river near the squatting community.

He showed Frontier images of the raid taken with his cell phone while moored on the Myanmar side of the river.

Thai soldiers conduct searches on migrant workers entering Thailand at Mae Sot from Myawaddy in Myanmar at one of the unofficial crossing points along the border. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

A recent newcomer to No Man’s Land is 12-year-old Maung Kyaw Lin (not his real name), who moved there to avoid being harassed by Myanmar police in nearby Myawaddy, where he was living on the street.

“They would arrest us and beat us up,” he said.

Kyaw Lin moved from Bago Region to Myawaddy several years ago with his family, but his father eloped to Bangkok with another woman, leaving the boy with his alcoholic mother.

Kyaw Lin started staying out all night with street children in Myawaddy. After his mother died, he moved in with an aunt but returned to life on the street.

He said he was “happy” to be living at No Man’s Land.

“Here I can get sleep, get a meal and make money; I am free. No one checks me,” Kyaw Lin said.

He said he makes between THB400 and THB500 (about K14,600 and K18,270) a day from begging and helping to carry the bags of undocumented migrant workers entering Thailand at one of the unofficial crossings. Kyaw Lin said he gives his earnings to a woman he calls his “stepmother” though they are not related.

The boy claimed to be well fed at his new home, but the morning I met him he was hungry.

In October, the government announced a crackdown on criminal gangs in Yangon and Mandalay that exploit children and the elderly by making them beg, the Irrawaddy reported.

Schoolchildren in Mae Sot watch on as a Thai soldier patrols close to the border. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

U Soe Kyi, spokesperson of the Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement, was quoted as saying a plan was being prepared to arrest the gangs but he did not indicate if the crackdown would be extended to border areas where the exploitation of children is common.

Asked if he wanted to go to school, Kyaw Lin, who is illiterate, said he did, but washing clothes, fetching water and earning his daily keep did not leave much time for attending classes.

Some of the children at No Man’s Land had attended classes at the Agape Orphanage and Boarding School, a migrant education school in Mae Sot. But that changed in 2013, when a headmaster fled to Myanmar after being accused of raping some female students.

The new school management introduced a stricter registration process and the students from No Man’s Land missed a deadline. They never returned to classes, said Daw Thinzar Oo, the school’s head boarding instructor.

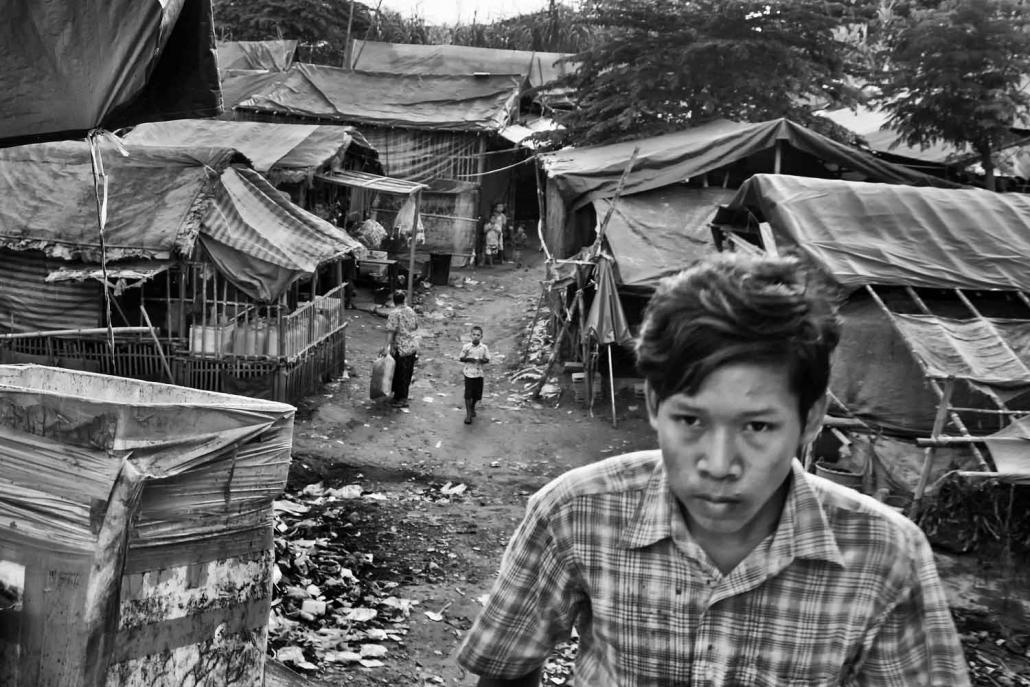

_dsf4369_1.jpg

A collection of makeshift homes in ‘No Man’s Land’. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

She said the former headmaster had badly wanted No Man’s Land children to have the opportunity to learn and would pick them up from the border in his bus and return them at the end of the day.

Thinzar Oo said it was sometimes difficult to convince parents that their children needed to attend school because the priority of poor families was making enough money to survive.

“The parents don’t care about an education for their children because if they go to school they can’t help support the family,” she said.

Sometimes parents send the youngest child to school because they typically generate the least income for the family.

“They are different from the other children,” Thinzar Oo said, adding that they were more likely to get into fights. But some were quite “clever” and they were usually better at mathematics than other students, she said, alluding to their experience in buying and selling.

Thai soldiers conduct searches on migrant workers entering Thailand at Mae Sot from Myawaddy in Myanmar at one of the unofficial crossing points along the border. (Brennan O’Connor / Frontier)

Thinzar Oo said children as young as 11 from No Man’s Land had come to school under the influence of drugs such as ya ba (methamphetamine). She suspected some of them had consumed drugs given to them by their parents to sell.

In 2013, members of the Kaw Moo Ra Karen Youth Group launched a drug raid on No Man’s Land. A Karen News report quoted the group’s chairperson, Saw Moses, as saying the raid was sanctioned by the Border Guard Force and Myawaddy Township police and was for the good of Kayin youth, many of whom had become addicts.

The group detained three suspects who were reportedly in possession of 5,000 ya ba tablets, 2.4 kilograms of marijuana, an M-16 assault rifle, three other guns, ammunition, and a home-made grenade. The suspects were handed over to Myawaddy police.

After night falls in No Man’s Land, Kyaw Lin dares not venture outside his new home.

“Every night there is shouting and fighting,” he said, adding that his stepmother told him to ignore the violence outside the house.

“I can’t sleep well; it’s very noisy,” Kyaw Lin said.