The recent formation of an ethnic affairs committee shows the National League for Democracy plans to compete with ethnic minority parties in next year’s general election.

By YE MON | FRONTIER

THE BATTLE for the ethnic minority vote in next year’s general election is heating up.

Prospects for an alliance between the National League for Democracy and ethnic parties already appear slim. In a first step towards wooing ethnic voters, the NLD established an ethnic affairs committee at a meeting of its central committee on September 21 and 22.

NLD vice chairman Dr Zaw Myint Maung told a news conference after the meeting that the party needed to have a strategic plan to compete against ethnic parties next year.

He said the creation of the ethnic affairs committee, the members of which include the chief ministers of Rakhine and Kayin states, was an example of the attention and care that the NLD devoted to ethnic affairs.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“We formed the ethnic affairs committee to emphasise” ethnic affairs, said Zaw Myint Maung, who also urged members of ethnic nationalities to join the NLD.

The decision to form the committee reflects the perceived strengthening of some ethnic parties since the 2015 election, and disappointment among some ethnic minority voters at the NLD’s performance in government.

A series of mergers is likely to consolidate the ethnic vote in many states, where the aspirations of multiple ethnic parties in 2015 were thwarted in part by split votes.

The NLD has been criticised over the construction in Kachin and Kayah states of statues of independence hero Bogyoke Aung San, the father of State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, and the naming of a bridge after him in Mon State. There is also controversy in Chin State over plans to erect an Aung San statue.

But Myanmar’s demographics and political system mean there are few electoral incentives for the NLD to create formal alliances with ethnic parties.

Around 60 percent of seats are in areas of the country dominated by the majority Bamar. Many constituencies in the seven ethnic minority states – particularly urban areas – have sizeable ethnic Bamar populations.

The first-past-the-post voting system and the manner in which government is formed after the election further diminish the usefulness of an alliance between a strong Bamar party like the NLD and ethnic minority parties.

Given the NLD’s support in Bamar areas, there’s a strong chance that it could once again win enough seats to choose the president without relying on the support of other parties.

If the party does need additional votes, it could cut a deal after the election. For now, it makes more strategic sense for the NLD to double down and focus resources on competing against the ethnic parties.

NLD spokesperson U Aung Shin said that the NLD would not make an alliance with any political party prior to the election.

“Our current position is that we will not work together with the other parties, but that may change after the election,” he said.

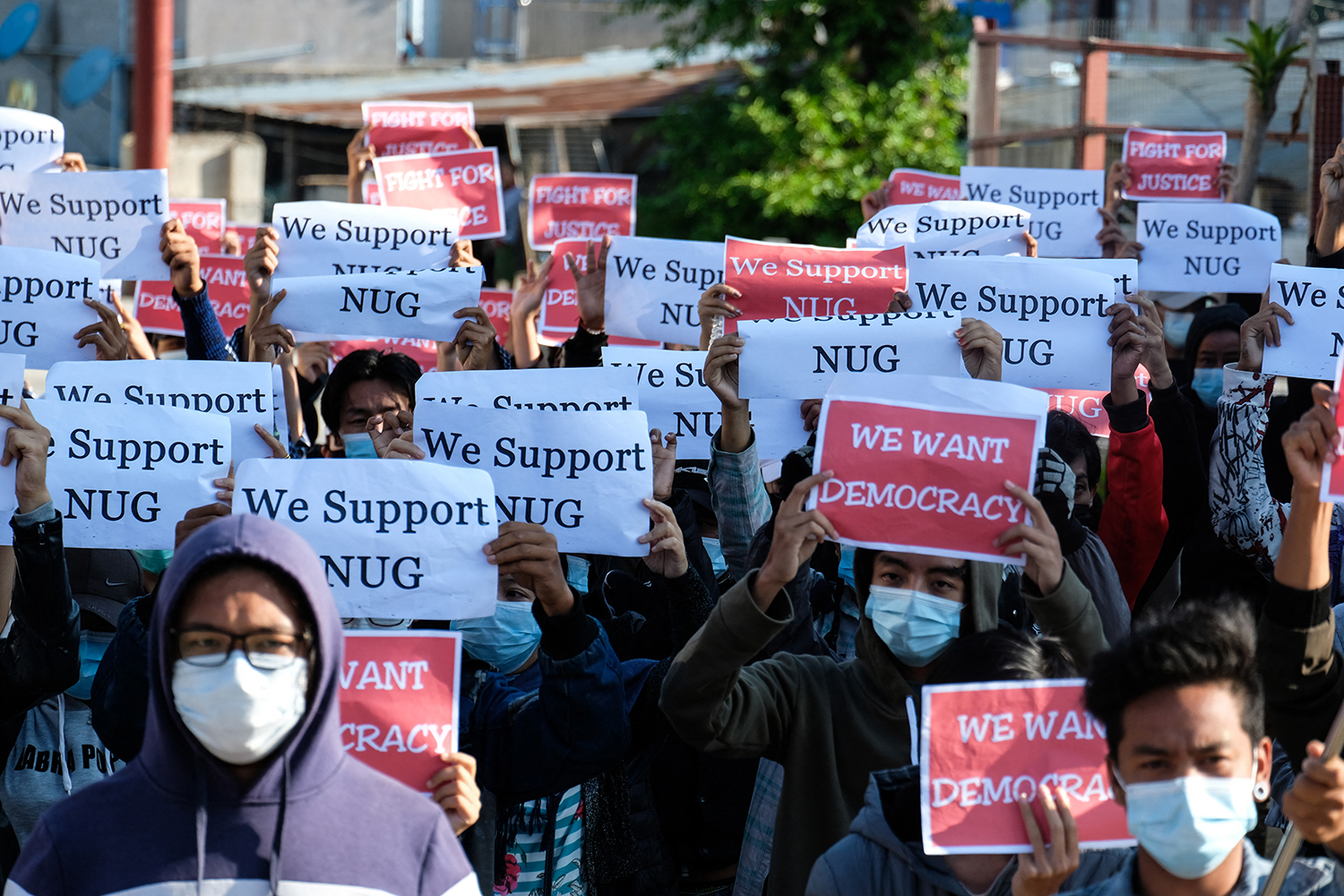

The NLD has already ruled out an alliance with ethnic parties in the 2020 election and will seek to replicate its strong showing in 2015. (AFP)

From allies to rivals

The NLD hasn’t always seen ethnic parties as rivals. Under military rule, it enjoyed a close relationship with some ethnic parties, particularly members of a group known as the United Nationalities Alliance.

Members of the NLD attended some regular meetings and conferences of the UNA, which was formed in 2002 by the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy, Mon National Party, Zomi Congress for Democracy, Kachin National Democracy Congress, Kayan National Party, Shan State Kokang Democratic Party and Kayin National Party.

However, in the 2015 election the NLD competed against UNA members and, after its victory, formed a government on its own. This prompted accusations from some that it had failed to support ethnic nationalities and ignored its relationship with the UNA.

Ethnic parties were disappointed by the NLD’s attitude because they thought it would pay more attention to the interests of ethnic nationalities, U Myo Kyaw, general secretary of the Arakan League for Democracy, told Frontier.

In particular, they were upset that it appointed party members as chief ministers in Shan and Rakhine states, despite not winning a majority of seats there.

“The NLD could have appointed chief ministers from the ethnic party that won the most seats if it wanted to show that it cared for and supported those parties, but it didn’t happen,” Myo Kyaw said, adding that the NLD’s stand on appointing chief ministers was decided before the election.

Ethnic parties are also disappointed that the NLD has shown no interest in changing its policy on the appointment of chief ministers in its push to amend the constitution.

Of the 114 proposed changes that the NLD has submitted to the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw Constitution Review Amendment Committee none concerns section 261, which deals with the appointment by the president of chief ministers of the states and regions.

A Shan Nationalities League for Democracy convoy in Wan Hai in 2017. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Merging of ethnic parties

In recognition that votes split among multiple ethnic parties cost them seats in 2015, there have been moves in Chin, Kachin, Kayin, Kayah and Mon states to merge ethnic parties so that they have a better chance against the NLD and Union Solidarity and Development Party in 2020.

Merger agreements have resulted in the creation of the Kachin State People’s Party, Chin National League for Democracy, Karen National Democratic Party and Kayah State Democratic Party.

While the NLD is not interested in an alliance, other Bamar parties have discussed the possibility with the newly formed ethnic parties.

USDP spokesperson U Nandar Hla Myint said it was prepared to ally with other parties that wanted the people and the nation to be developed. The USDP understood the needs of ethnic people, he said.

“I can’t comment in detail about our negotiations to ally with ethnic parties,” he said. “But we will support and work to deliver ethnic people the things they need.”

KNDP chairman Mahn Aung Pyi Soe said the party, which was formed last year by merging the Kayin Democratic Party, Kayin State Democracy and Development Party and Kayin National Democratic Party, had rejected an approach by the USDP. He added that the KNDP had no intention of approaching a Bamar party to form an alliance before the election. “The USDP has approached us to make an alliance, but we don’t like the USDP,” he said.

The Mon Unity Party was formed on July 11 as a merger between the All Mon Regions Democracy Party and the Mon National Party.

The MUP’s Naing San Tin said the party had been approached by the People’s Party, established by 88 Generation student leaders, and the Union Betterment Party, headed by former Pyithu Hluttaw speaker and leading member of the military junta, U Shwe Mann, but was yet to decide whether to form an alliance with them ahead of the 2020 election.

The Kachin State People’s Party was formed in June by the Kachin Democratic Party, Kachin State Democracy Party and Union and Democracy Party of Kachin State.

KSPP central executive committee member Daw Doi Bu said the party was yet to discuss whether to join forces with other parties and that it had received no offers to ally with the major parties.

“Even if we wanted to ally with major parties, some of them have already announced that they would not form alliances,” she told Frontier.

For the new ethnic parties, Rakhine State provides a cautionary tale of what can happen when mergers go wrong.

The Arakan National Party, formed by a merger agreed in 2013 by the Rakhine Nationalities Development Party and the Arakan League for Democracy, was the most successful of the ethnic parties in the 2015 election, but has since been torn apart by the rivalry between factions headed by members of the RNDP and ALD.

The ALD’s Myo Kyaw acknowledged that party unification was a positive step but it was important all of those involved shared a common vision.

“Policies are very important … unification is not just about the election result,” he said.

Workers clean a statue of Myanmar independence hero General Aung San in Myitkyina, the capital of Kachin State, after it was defaced with paint. (AFP)

Statues and bridges

But ethnic parties may get a boost from the NLD’s handling of the building of statues of Aung San in minority areas, which has angered some activists.

As a stinging result from the 2017 by-election shows, the NLD could struggle to replicate its strong showing in Mon State in 2015. The by-election was affected by vehement opposition to the party’s insistence on naming after Aung San a bridge over the Thanlwin River linking Mawlamyine with Bilu Kyun island.

Thousands of Mon had demonstrated against the decision, which the NLD had pushed through the Union Hluttaw a mere two weeks before the by-election for the Pyithu Hluttaw seat of Chaungzon, which the party lost to the USDP. As Frontier observed in a editorial, the decision “suggests a lack of political judgement that borders on the absurd”.

Naing San Tin, joint secretary of the Mon Unity Party, told Frontier that the NLD’s stand over the bridge and the Aung San statues might prompt those who voted for the party in 2015 to reconsider their support next year.

He said he expects the NLD to avoid any similar controversies until the election.

“I think that the NLD will consider these issues and draw lessons from them,” he said.

In Kayah, the decision to erect the statue in the state capital, Loikaw, generated heated opposition among some sections of the community and resulted in the arrest of six youth activists who had led protests against the project.

The Kayah State government took action against the six under the Citizens Privacy and Security Law over accusations that they had described supporters of the project as traitors of the Karenni people and enemies of ethnic unity. They face up to three years’ imprisonment and have been remanded in custody during the trial, which is continuing.

The controversy could have implications for the NLD in the 2020 election, in which it will face competition from the Kayah State Democratic Party, which was formed in 2017. In the election two years earlier, the NLD won 11 of the 15 contested seats in the 20-member Kayah Hluttaw – in which the other four elected seats went to the USDP – as well of six of the seven Pyithu Hluttaw seats and nine of the 12 Amyotha Hluttaw seats.

However, KSDP vice chairman 1 Sai Naing Naing Htwe said that while the statue issue had created problems for the NLD in ethnic areas, he wasn’t sure whether it would impact the election result. His party did not plan to raise the issue during its election campaign, he said. “We are preparing to compete with and beat the NLD in 2020,” he said.

Aung Shin said the NLD would consider how to overcome the consequences of the bridge and statue controversies and other issues, such as the arrest of ethnic activists. There was no concern in the party that it would lose the 2020 election because of its activities in the ethnic states, he said, and the new ethnic affairs committee would shore up its support.

“One of the main reasons why we formed the ethnic affairs committee was to get the best outcome in the 2020 election,” Aung Shin said.