The recent spike in the number of journalists being arrested has brought attention to the Myanmar Press Council’s inability to mediate in disputes.

By NYAN HLAING LYNN | FRONTIER

WHEN THE interim Myanmar Press Council was formed in September 2012, it was seen as yet another signal that, after decades of heavy censorship, the media industry in the country was opening up. Coming less than a month after the U Thein Sein-led administration had scrapped pre-publication censorship, optimism was high.

Even several years later, in October 2015, when Thein Sein’s administration made the 23-member MPC a permanent fixture of Myanmar’s media landscape, there was a feeling that press freedom was moving in the right direction.

However, just over 18 months later and things aren’t looking quite so rosy. A recent rise in the arrest of journalists has spooked the industry, and few believe that the council, which was established to mediate in disputes involving journalists, can offer much in the way of help.

“I forget that the Myanmar Press Council even exists,” said U Thiha Thway, the Myanmar correspondent for Japanese news agency NHK and who has worked as a journalist in the country for 15 years. His comments came shortly after U Kyaw Min Swe, chief editor of The Voice, was charged under the notorious 66(d) clause of the Telecommunications Act, after the daily published an article deemed defamatory of the military. Weeks later, three journalists were arrested and charged under Article 17(1) of the colonial-era Unlawful Associations Act for entering territory controlled by the Ta’ang National Liberation Army.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

According to the Myanmar Media Law, which was enacted in 2014, journalists operating in the country have the right to “freely criticise, point out or recommend operating procedures of the legislative, the executive and judiciary in conformity within the constitution”. They also have the right to investigate, publish and broadcast information “to which every citizen is entitled”.

Absent from the terminology is the Tatmadaw, which has been the plaintiff in the two most recent cases brought against journalists. However, some recent cases involving reporters – most notably that of Eleven Media CEO U Than Htut Aung and chief editor U Wai Phyo, who are being charged under 66(d) – the complaint was made after a member of the National League for Democracy government was criticised.

“The council is completely different from what I expected,” Thiha Thway told Frontier. “It doesn’t seem to have any influence either on the authorities or the media, and it doesn’t feel like we can rely on it.”

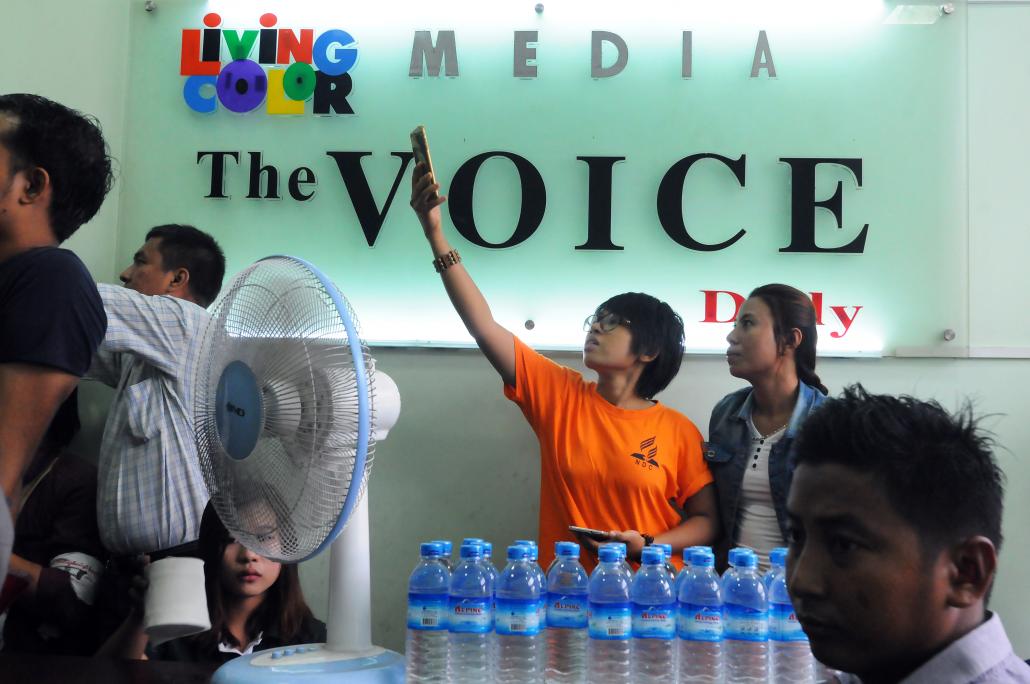

Journalists attend an event shortly after U Kyaw Min Swe, the editor of The Voice, was arrested under section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Thiha Thway is not the only media professional working in Myanmar who has been disappointed by the lack of influence held by the MPC, which is funded by the Ministry of Information but is supposed to operate independently from the government.

“When I say that I want the council to have greater influence is not because I want to attack members of the council, but because I want the mechanisms of the council to operate effectively and help settle the problems the media are facing,” said Daw Aye Tu San, an editor at 7Day newspaper.

According to Section 38 of the media by laws, enacted on June 17, 2015, during any complaint the council is tasked with summoning both the complainant and defendant to coordinate a meeting.

U Aung Soe, a senior editor at The Voice, said that after Kyaw Min Swe was charged, the publication asked the council to arrange a face-to-face meeting with representatives from the Tatmadaw who had opened the case, but to no avail.

The council was also unable to intervene in the case of the journalists arrested in northern Shan State last month. The media law stipulates that journalists have the right to travel to war zones – the TNLA has been in active conflict with the Tatmadaw since November – without being detained by security forces and having their equipment confiscated or destroyed.

On June 27, the council published on its Facebook page a letter it had sent to Commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing calling for the release of the reporters, but did not receive a response.

“Currently, the ability of the council is only to send and receive letters between the complainant and the defendant,” said Aung Soe.

According to the media law, if a journalist is accused of breaking the law, the plaintiff must first make a complaint to the council. The council is then tasked with arranging a meeting between the two parties to try and reach an agreement; under Section 23 of the law, if an agreement cannot be reached only then can the complainant open a case.

As developments in recent weeks have shown, the reality is very different with journalists being detained even before the council is informed. In the case of the three journalists in Shan State, after news of their arrest was posted on the Facebook page of Min Aung Hlaing, information of their whereabouts did not emerge for two days.

Lawi Weng, left, one of the reporters arrested in late June in northern Shan State after attending an event in territory controlled by the TNLA. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

Members of the council interviewed by Frontier admitted to some shortcomings but insisted they were doing the best they could in the circumstances, and were also doing so voluntarily.

According to council member U Myint Kyaw only eight of its 23 members are journalists; the rest include the speakers of the Pyithu and Amyotha hluttaws, as well as publishers, poets, cartoonists and representatives from cultural, legal, scientific and technology organisations.

U Zeya Hlaing, who is also a member of the council and founder and editor of the investigative Mawkun Magazine said that one of the issues it faces is that the non-journalists on the council do not fully understand the job of a journalist.

U San Yu Kyaw, principal of the Mandalay School of Journalism, called on journalists who are members of the MPC to quit and to form a separate council. However, members interviewed said to do so would be counterproductive, as the council would continue to operate. Therefore, they argue, to have some journalists onboard is better than having none.

San Yu Kyaw also said that the council should include members from all 14 states and regions, to make it wholly representative of the country’s media industry, and not only focused on Yangon.

Zeya Hlaing called on all stakeholders within the media industry to come together to work out measures that would make the council more effective, and it’s an approach that its critics agree with.

Thiha Thwe, the NHK correspondent, said a proposal should be submitted to parliament to reorganise the council.

“Everyone should come together to discuss how to organise a council that will be able to protect journalists,” he said.

TOP PHOTO: Protesters attend an event calling on the government to scrap the controversial section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)