Worries for residents near the landfill, which was the scene of a huge, weeks-long fire in April and May, include pollution and compensation for their land.

By KYAW YE LYNN | FRONTIER

A FIRE THAT burned for weeks at a massive garbage dump on Yangon’s outskirts and polluted the atmosphere of several townships with foul-smelling smoke has focused attention on worsening air quality in the commercial capital.

The fire at the sprawling Htein Bin landfill in outer northwestern Hlaing Tharyar Township began on April 21 and spread quickly until it was consuming more than half of the dump, which covers 98 hectares (244 acres).

The blaze was fuelled by methane produced by decaying vegetation and other waste. It was not brought under complete control until May 14, said U Aung Myint Maw, deputy head of the Environmental Conservation and Cleaning Department at Yangon City Development Committee.

“The fire was caused by the reaction between oxygen in the air and methane gas produced by the garbage,” he said.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Yangon regional government said 800 personnel from the Myanmar Fire Services Department, YCDC and Yangon Military Command were deployed to fight the fire, which was finally brought under control after it was smothered by 1,850 gallons (about 8,182 litres) of special foam imported from Thailand.

Aung Myint Maw said the fire has been completely extinguished, a classification the Fire Department calls Level 0.

“However, we are still monitoring the site with four fire trucks,” he told Frontier on May 21.

U Aung Myint Maw, deputy head of the Environmental Conservation and Cleaning Department at Yangon City Development Committee (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

Smoke from the nearly month-long fire resulted in a noticeable deterioration in air quality in areas near the landfill and dozens of people, including children, were hospitalised with respiratory problems.

Aung Myint Maw said data from 15 air quality monitoring devices installed throughout the city by his department showed high levels of methane and carbon dioxide near rubbish dumps. The data also showed high levels of carbon dioxide in the downtown area and of sulphur dioxide in industrial zones, he said. Vehicles are a major source of carbon dioxide.

He said that years of people dumping their waste at the site meant it was a challenge for the department to reduce air pollution in the local area, adding that the soil and water had also been contaminated.

“We just have a small budget for waste management,” he said.

“The collection fees cover only about a third of the cost and only about 480,000 out of Yangon’s one million households pay the fees,” Aung Myint Maw said, adding that changing the disposal system would help alleviate some of the pollution problems.

Yangon Mayor U Maung Maung Soe told journalists in April that the regional government was planning to call tenders for a project to generate electricity at rubbish dumps by burning methane.

In 2012, South Korean company Chasson International won a tender to build a methane-burning power plant at Htein Bin, but the project didn’t go ahead because of a disagreement over tariffs. A separate planned project, by local firm Zeyar & Associates, at the Chaung dump in South Dagon Township, also failed to proceed for the same reason. Both tenders were run by YCDC.

“The maximum price the government would pay was K90 a unit, but the companies wanted K150 or K160 a unit,” said Aung Myint Maw.

For business operations, standard electricity rates start at K75 a unit up to 500 units, K100 for 501 to 10,000 units, K125 for 10,001 to 50,000 units and K150 for 50,001 to 300,000. Consumption above 300,001 units is charged at K100 a unit.

According to a statement published by the Ministry of Electricity and Energy last year, the government was spending K333 billion a year on subsidied and supply electricity to 37 percent of the country.

“If those projects had been implemented, such a big fire would not have happened,” said Aung Myint Maw.

For the revived plan, the government has committed to paying subsidies, Aung Myint Maw said.

Changing the garbage fee collection system could also be beneficial, he said.

“Currently, we collect the fees door-to-door during office hours, when people are often at work. If we change the collection system to the way people pay for electricity [which people can pay online], that would work,” he said.

Although the effect of smoke pollution from the Htein Bin fire on nearby communities dominated the headlines for days, former farmers in the area said their suffering also deserved attention.

The farmers at Hlaing Tharyar’s Kalagyi Su village tract said they had not been compensated for 688 acres (278ha) confiscated by the military government in 1996 and 1997 and handed to the YCDC’s Environmental Conservation and Cleaning Department to establish cemeteries and other facilities at Htein Bin.

“The junta demolished the Kyandaw cemetery in Kamaryut Township in 1996 and the remains were moved here,” said Kalagyi Su resident U Myint Swe, as he pointed to one of the cemeteries.

His father, U Aung Myint, had owned 27 acres and his father-in-law, nine acres. They were among 90 farmers whose land was seized in 1996.

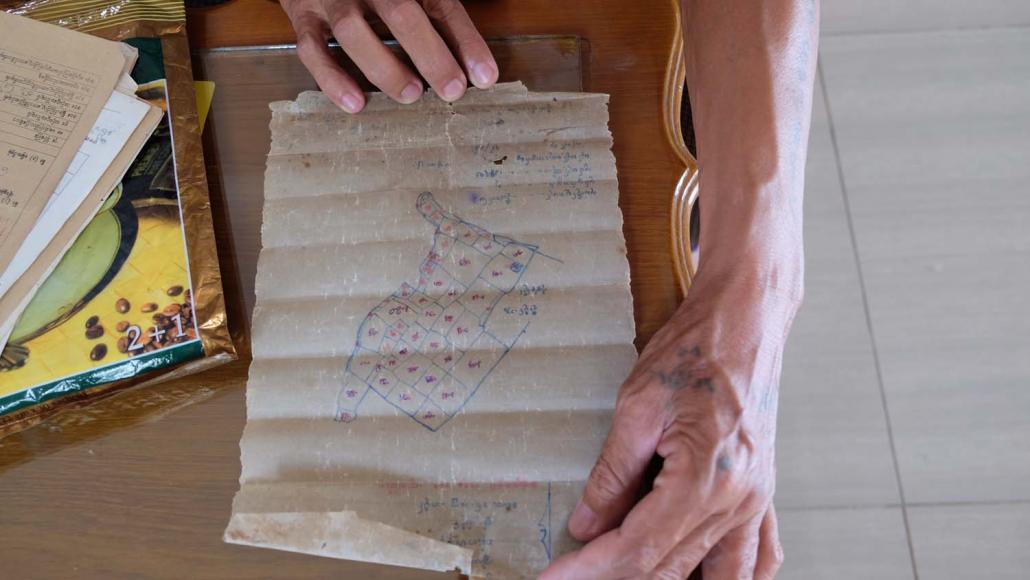

Farmer U Myint Swe holds a map showing plots that were confiscated by YCDC for a cemetery (Kyaw Ye Lynn | Frontier)

“As you know, when a junta leader asked you for something, you had no choice but to follow their plan,” Myint Swe told Frontier on April 17.

The farmers paid rent of up to 20 bags of paddy an acre and continued farming until 2012, when President U Thein Sein’s Union Solidarity and Development Party government enacted the Farmland Law, which promised fair compensation for confiscated land.

“After the law was enacted, YCDC stopped us from farming,” Myint Swe said.

“It is nearly six years since the law [was enacted], but we haven’t received a single kyat from the department as compensation,” he said.

In 2015, the farmers rejected a compensation offer from the previous regional government of K2.5 million an acre for a total of 625 acres because they said it was below the amount paid by YCDC for adjoining land.

“YCDC Revenue Department paid K7.5 million an acre for more than 100 acres next to our land last year,” Aung Myint said, referring to land that has since been developed and includes the Dagon Ayeyar highway bus station.

“How can we accept such kind of discrimination?” he said.

The previous government had claimed land use was the reason for the difference in compensation, said the Yangon Region lawmaker who represents the area. A higher rate had been paid for land that was being used for projects that were profitable.

Yangon Region MP U Myat Min Thu (National League for Democracy, Hlaing Tharyar-2) disputed this.

“YCDC’s Revenue Department earns a lot of money and can pay a high compensation rate. That’s what they said: it’s an unacceptable reason,” he said.

Hlaing Tharyar’s farmland management committee reviewed the case, confirmed the affected area was 688 acres and had recommended the government increase its compensation offer, the MP, who is also a member of the village tract-level committee, told Frontier on April 19.

“They will be compensated next fiscal year,” Myat Min Thu said, but he declined to say what compensation would be paid.

The rate would be decided by the regional government, he said, adding that farmers had demanded compensation as high as K20 million an acre.

“If the rate is not fair, the compensation payment will be delayed again. But they will be compensated anyway,” he said.

Aung Myint Maw confirmed that the farmers will be paid K10 million an acre, more than four times the offer they rejected in 2015.

“The government has agreed to compensate the farmers for their land and they will be paid once the rate has been settled,” he said.

Aung Myint Maw said YCDC had used the confiscated 688 acres to establish five cemeteries, including three for Christians and one each for Muslims and those of Chinese descent, an animal breeding zone and the Htein Bin dump.

Htein Bin cemetery manager U Saw Myo Nyunt Thein said the farmers had caused him no trouble but he was aware they had faced trespassing charges a few years ago.

“It would be better that they receive compensation as soon as possible,” he told Frontier on May 19.

2016_1119_20301700.jpg

U Zaw Lay, son of U Phoe Chaw, a farmer whose land in Hlaing Tharyar Township was confiscated by YCDC (Kyaw Ye Lynn | Frontier)

However, Myat Min Thu told Frontier on May 29 that the apparent compensation had not been included in the regional budget for the 2018-19 financial year.

“We discussed the issue at regional parliament today. We have urged the regional government to include in the [budget for] this financial year, so the farmers receive the compensation next year,” he said.

“The farmers suffered a lot and their land was seized,” he said.

U Zaw Lay is a son of U Phoe Chaw, who lives at Kan Hla village in the Kalagyi Su village tract.

He told Frontier on April 23 that his father and other farmers had received a death threat in 2001 after unseasonal rain destroyed their crops and they were unable to pay rent.

Zaw Lay said a former army captain with the Environmental Conservation and Cleaning Department told the farmers they would be burnt alive unless they paid the rent on time.

“My father is a strong man and I never thought I would see him cry,” he said.

“When my father returned home after that threat was issued he cried like a baby.”