When a problem is identified or perceived, all too often the first response is still to draft a new law or regulation.

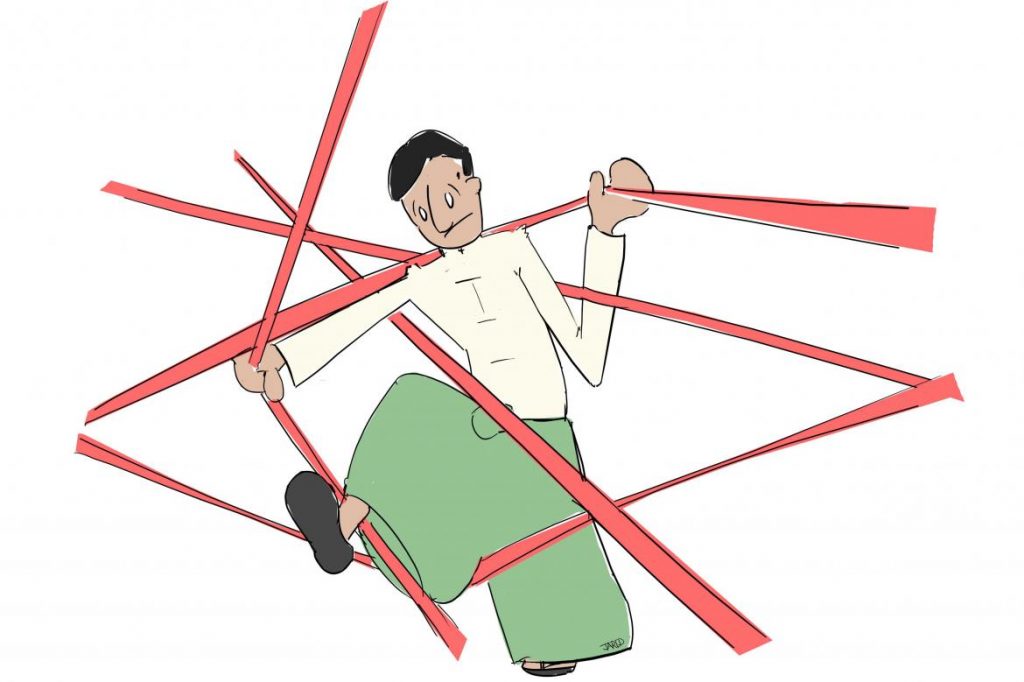

WHEN ECONOMIC reform is discussed in Myanmar, it’s often in terms of new rules, laws and regulations. This is understandable, in its own way: creating something instinctively feels like a positive achievement. But often the most impactful reforms are those that simply remove what is already there – or replace it with something much simpler and more straightforward.

It has probably been said once or twice before, but Myanmar is a maze of bureaucracy and red tape. If anything, the situation has got worse since the transition to democracy; the creation of a new parliament has unleashed a pent-up wave of law making, much of it haphazard and substandard. When a problem is identified or perceived, all too often the first response is still to draft a new law or regulation.

Now, we’re not saying that all tariffs and licences should be removed. Regulation has its place. Trade needs to be controlled to some extent. But each regulation should be subjected to some pretty stringent cost-benefit analysis.

Myanmar’s present trade regime – and the way it has been applied and enforced by various agencies, notably Customs – is clearly holding the country back. The main beneficiaries are the officials who can use the system’s complexity and opaqueness to extract payments, and the agents who know how to navigate it. Even the agents we interviewed were frustrated: not at having to make under-the-table payments, which they viewed as a fact of life and simply passed on to their clients, but at the fact that such payments were no guarantee of efficient service.

Unfortunately, most of us lose from this equation. We lose because inefficiencies and rent seeking add to the cost of imported items, and make Myanmar’s exports less competitive.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Well, here’s an easy reform: abolish export permits. The government could do it tomorrow if it wanted to. And when it’s finished that, review licensing requirements on imports and keep only the most essential.

This isn’t going to solve all of the roadblocks to improving Myanmar’s trade environment, which are also linked to institutional capacity, lack of hard infrastructure and limited access to trade financing. But it’s certainly going to be easiest way to kick-start the liberalisation process.

Unfortunately, the indications are that it’s going in the opposite direction. The Myanmar Times reported last week the Ministry of Commerce had added 3,345 items to its Export Negative List under the 2012 Export and Import Law. Any item on the list requires a permit to be exported.

But this effort to cut the red tape doesn’t need to be limited to trade and Customs. The government could do wonders for the country by simply conducting a methodical, sector-by-sector review of what’s on the books and reviewing whether these rules are still necessary or fit for purpose. If not then they should go.

This editorial first appeared in the March 15 issue of Frontier.