More expensive inputs, declining crop prices and a possible dearth of affordable credit could push millions of farmers into destitution and debt.

By FRONTIER

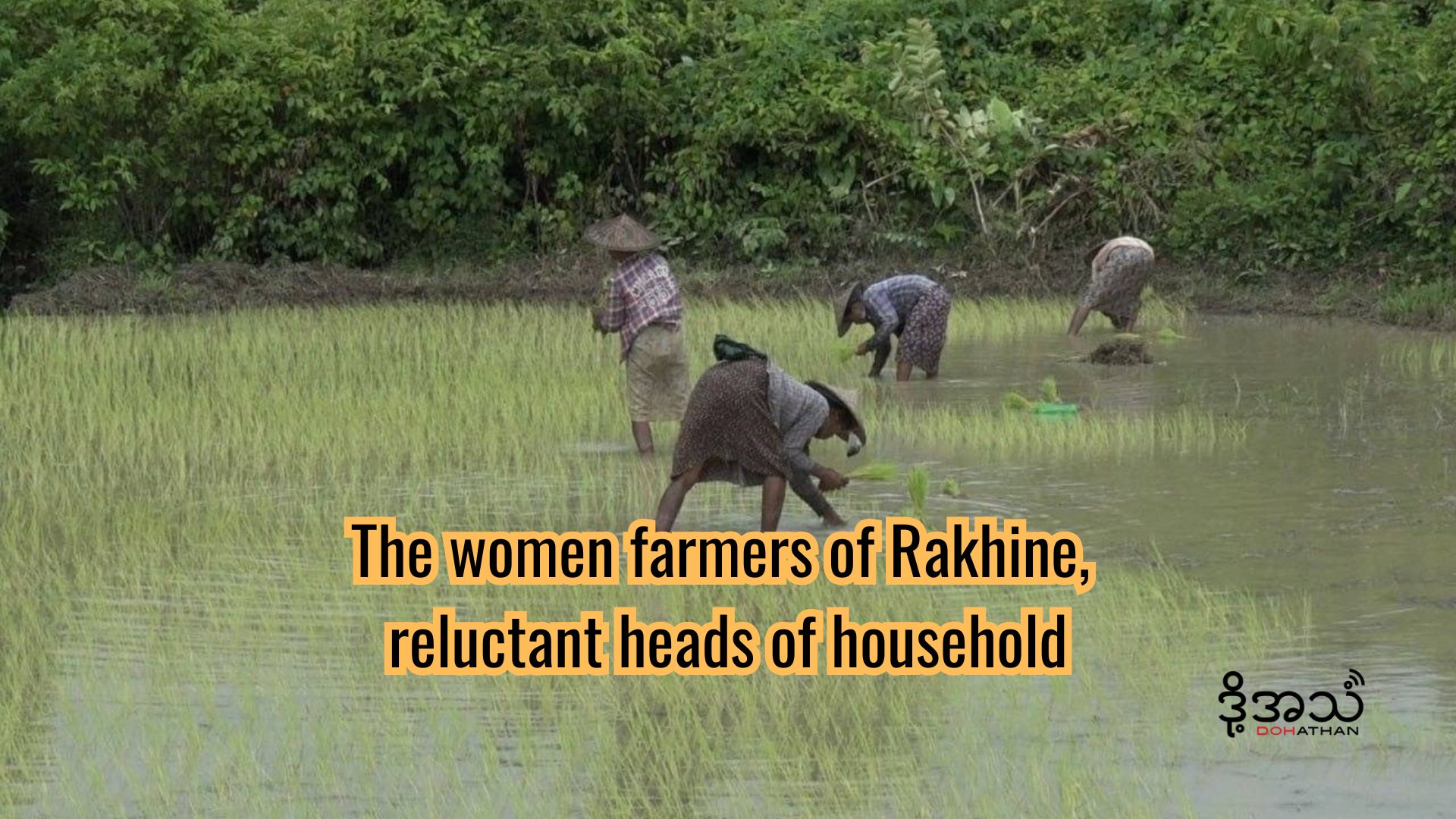

Throughout much of the country, Myanmar’s farmers are busy preparing their fields for the monsoon rice crop – the key annual event for a sector that accounts for about half of all Myanmar’s jobs and one-third of GDP.

This year, though, farmers’ faces are lined with worry over the political turmoil and how it might affect an already precarious existence.

The military coup has already led to higher prices for fertilisers and pesticides, and rising inflation is hiking their cost of living. At the same time, prices for some of the agricultural commodities produced by these farmers are falling. This, together with disruptions to transport and trade, threatens to wipe out their profits.

Farmers also worry about access to credit, without which many of them can’t afford the inputs needed to sow their fields. Although Nay Pyi Taw has announced that it will soon begin disbursing low-interest loans, farmers say they’ve so far heard nothing from the state-run agriculture bank – a primary source of rural credit – and some are also refusing to repay their loans from last year to show their opposition to the military regime.

This has left farmers unsure how much they should invest, or even whether they should cultivate at all in advance of the rains, which usually arrive in May and last until October.

“Every monsoon season I worry about how I’m going to pay for labour, fertiliser and pesticides,” said U Myint Aung, who farms eight acres (3.25ha) in Sarphyusu village in Ayeyarwady Region’s Danubyu Township. “But I think this year will be worse than ever.”

This could have devastating consequences for millions of rural households, many of which were already struggling due to the impacts of COVID-19 last year. In April, the World Bank warned that the fallout from the coup would likely “result in a sharp increase in poverty, heightened food security risks, and deeper destitution for those already poor”, and said the success of upcoming harvests would be “critical” for households reliant on agriculture.

Declining kyat, rising prices

The first problem facing farmers this year is that agriculture supply shops are refusing to sell fertiliser and pesticides on credit.

Normally farmers buy on credit and pay the shops back after harvesting their crops or after receiving a loan from the state-run Myanma Agricultural Development Bank, he said. “But this year, the shop owners will only sell for cash and we don’t have the money.”

Shop owners said they were demanding cash from farmers because the companies that supply fertiliser are also insisting on being paid in cash due to the difficulty of withdrawing cash from banks amid a coup-induced crisis in the financial sector.

“It’s not the same as before,” said the owner of a farm supplies shop in nearby Sagagyi village, also in Danubyu Township. “We have to pay as soon as we receive deliveries and because we need money we cannot sell to farmers on credit anymore.”

He said prices for agricultural inputs were rising by the day because most of the products are imported. Since the February 1 coup, the kyat has slumped from K1,335 to the US dollar to almost K1,700 – a decline of almost 30 percent – making imports more expensive.

Most brands of fertiliser have increased by around 15pc, but some have risen by as much as 40pc, he added.

“It’s difficult to predict the future financial situation. Sales are also lower than normal.”

Myint Aung said that even before the coup, farmers like himself had tried to economise on inputs. He said they could never afford to use fertiliser at the rate recommended by agrochemical companies, of two bags for every acre of paddy.

“Yesterday, I went to buy inputs, but the prices were unaffordable. I used to buy four bags of fertiliser for my eight acres, but this year I only bought three bags. I have to conserve money to be able to buy pesticides,” he said.

The Danubyu Township representative of an agricultural chemicals company said sales were down by up to 20pc on the same period last year.

A March survey of input retailers by the International Food Policy Research Institute found that most were already facing a decline in sales compared to a year ago, and this decline was likely to accelerate as prices rose further.

“The combination of uncertain crop prices, higher costs to access markets, financial market disruptions, and expected increases in input prices all point to lower farm investment in production inputs for the coming monsoon season,” it said.

U Tin Soe, a paddy and beans and pulses trader in Danubyu, agreed that the reduced use of fertilisers and pesticides will result in a decline in crop yields.

“Farmers will suffer a lot this year. If crop yields and quality are bad, prices will fall and they will lose money. It would be good if the government could provide assistance to farmers,” he said.

Some farmers are already suffering. Onion growers, who harvest during the cool season ending around February, saw prices fall from K650 a viss (1 viss is equal to 1.63 kilogrammes) to as low as K250 a viss, well below the cost of production.

“Prices are down and because of the political situation transportation has become more difficult,” said U Aung Ko Myint, a grower from Taung village, near the Sagaing Region capital Monywa.

“We don’t have money left over to invest in the next crop and moneylenders are reluctant to give out new loans,” he said. “But at the same time, the US dollar is rising so all our inputs are getting more expensive. It’s a really difficult time for us.”

Uncertain farm loans

Even when they are able to buy inputs on credit, farmers need additional capital to invest in preparing their land and growing paddy. With few private banks interested in offering loans to farmers, many rely in part on credit from state-owned MADB.

These loans have never been enough to cover all the costs of cultivation, and farmers were often heavily dependent on loans from informal lenders that could incur interest as high as 10pc a month.

The MADB allows eligible farmers to borrow K150,000 an acre for monsoon paddy and K100,000 an acre for winter crops, up to a limit of 10 acres, and existing loans must be repaid in full before new ones are granted. Last year, government figures show the bank disbursed K1.75 trillion in agricultural loans, the equivalent of US$1.3 billion at the time.

The bank typically charges 8pc interest a year. Due to the impact of COVID-19, however, the NLD government last year reduced the interest rate to 5pc, and also extended the deadline for repaying monsoon crop loans to July 31.

But the political upheaval of the past few months has left many farmers in doubt as to whether loans will be provided at all this year.

In a normal year, MADB begins contacting farmers to make repayments in February, and loans are disbursed from May. Village tract administrators make a list of farmers who want to borrow money and send it to the MADB, which then sends out loan contract forms. A few weeks after the administrators have returned the completed contract forms to the bank, farmers can withdraw the money. In practice, loans are often delayed, and farmers borrow from informal lenders to cover their costs until they receive the cash from MADB.

Since taking power, though, the regime said nothing about either repayments or new monsoon loans for more than three months. Many MADB staff also joined the Civil Disobedience Movement to show their opposition to the military coup, which delayed the repayment of winter crop loans. In some cases, these strikes are continuing; just last week, the regime suspended 60 MADB staff based in Yangon who had refused to return to work.

Then, on May 20, state newspapers published a notice from MADB saying it planned to hand out loans from May 26 to September 30. It said that although the repayment deadline for loans from last year’s monsoon season had been extended, farmers who wanted loans this year should contact the bank “as soon as possible” to clear their debt.

This announcement has been met with some scepticism. Daw Mya Thet Mu from Danubyu Township’s Htonepone village said when she went to her local MADB branch on May 14 to repay her winter crop loan, bank staff said they had no information on monsoon loans, and updates would be announced through village tract administrators.

“The [May 20] statement is so general. The government used to announce exactly how much they will lend this year, but it didn’t have any information like that,” said the 61-year-old farmer. “This time last year we had already applied for a loan through the village tract administrator … I’m worried about what will happen if farmers cannot borrow from the government for the monsoon paddy crop.”

Some suspect the authorities might be making vague promises of new loans to ensure farmers repay their existing debts. Even before the announcement, village tract administrators appointed by the military regime were coming under pressure to ensure that farmers repay their winter crop loans.

U Aung Kyaw Oo, the administrator of Sagagyi village tract, near Sarphyusu village, said the Danubyu Township General Administration Department office had summoned the township’s village tract administrators to a meeting after the mid-April Thingyan festival and directed them to form an agricultural affairs committee in each village, with instructions to chase up loan repayments in the community.

He said he wasn’t even aware of the MADB announcement in state newspapers.

“When and where was the statement released?” asked Aung Kyaw Oo. “We haven’t received any information on new loans – just pressure to make sure farmers pay back their old loans. I haven’t even collected a list of farmers who want loans, so it’s impossible for the bank to start giving out money from May 26. It looks like a lie or trick.”

The uncertainty over whether monsoon paddy loans will be available this year has forced farmers to consider other ways to raise capital. Myint Aung, from Sarphyusu village, said he might have to pawn his wife’s gold necklace.

“The income we earn from farming is for repaying loans and feeding the family. If the government can’t provide the loans, we will face a crisis,” he said.

Boycott calls

While some farmers are desperate to access low-interest loans from MADB, others are refusing to pay back their old loans to show their anger at the military takeover and deprive the regime of funds.

The refusal to repay is part of a broader boycott movement that has targeted everything from military-owned beer brands to lottery tickets and electricity bills.

The Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, formed shortly after the coup by mostly NLD lawmakers elected in November last year, has encouraged these efforts. For instance, on March 12, it announced a one-year deferral of agricultural loan repayments, adding that farmers would not have to pay any additional fees or interest.

One farmer from central Myanmar’s Magway Region, who asked not to be named, told Frontier he would not be repaying the K550,000 he still owes from last year.

“In previous years, the head of the village informed us with a loudspeaker about the final date to repay our loans. This year we haven’t heard anything, but even if they ask us, we won’t do it,” said the farmer from Taw Ywar village in Myaing Township, who grows paddy, peanuts and sesame on 16 acres.

“Many people in my village won’t pay because we don’t want to give money to the military – we hate them. We will only pay it back if Daw Aung San Suu Kyi asks us to do it,” he said.

The farmer said that without access to MADB loans he would likely have to borrow from moneylenders to pay labourers at harvest time. “The interest is high but we have no choice. Anyway, we’re used to being trapped in a cycle of debt.”

Farmer U Nay Naing Lin, 41, from Mingin Township in Sagaing Region, said about 80pc of farmers in his area were yet to repay the loans because the CRPH announced that repayments had been postponed.

But he said the lack of communication from MADB had created even less incentive to pay back old debts, as many farmers now think they will not be able to access new loans anyway.

“This is just going to make life harder for farmers in the months ahead. When the rain comes, of course they will want to grow and they’ll have to borrow with high interest from moneylenders instead,” Nay Naing Lin said.

“For me, I’m lucky because I also run a cargo truck between Monywa and Mingin, so I don’t rely on farming too much. But for other farmers, it’s going to be really difficult.”

Another farmer, from Nipataw Sanpya village in Magway’s Yesagyo Township, said she was undecided about whether she will pay back her K1.1 million debt.

“I’ve heard CRPH postponed the repayment until 2022 but the military government is demanding we clear our debts,” she said. “Most people don’t want to repay. I’m waiting to see how others respond – if many people pay back their debt, I will have to repay mine too. If not, I won’t pay it either.”

Either way, she said, she will not take a new loan from the “dictators”. “I don’t want money from them, even if it means I don’t have enough money for the next season,” she said. “I’ll find another way to get by.”

Despite this talk, Mya Thet Mu from Danubyu said she was sceptical that many farmers would boycott repayments because in doing so they risked more than the denial of further credit. When farmers take out loans they have to give their Form 7 land ownership document to MADB as collateral, she said, which means farmers who fail to repay their loans risk losing their land.

“If we don’t have our Form 7, we can’t sell our land or even prove that we own it,” she said.