Migrants from China have settled in Myanmar for centuries but some more recent arrivals keep a low profile because their presence is illegal in the country they call home.

By ANN WANG | FRONTIER

ABOUT 10 years ago, Ko Aung Kyaw Oo* hopped on a motorbike taxi in the Chinese border town of Ruili. A few minutes later he was dropped off in Muse, on the Myanmar side. Now in his 40s, he has never returned to China, nor does he want to.

“I didn’t want to be a communist anymore,” he said, explaining that it was the only reason why he left his home in southern China to live in Myanmar, where he is a resident of northern Shan State and wants to remain anonymous.

People from China have been migrating to Myanmar for centuries.

Ms Stephanie Olinga-Shannon, the co-author with Mr Nicholas Farrelly of Establishing Contemporary Chinese Life in Myanmar, said migration from China can be separated into different phases.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Aung Kyaw Oo takes part in prayers that mark the start of another school day. (Ann Wang / Frontier)

The first big wave came during the colonial period, when most Chinese entered Myanmar through its ports, coming from the other British colonies of Malaya and Singapore. Workers from Yunnan had also crossed the border to work in the mines and teak plantations in northern Burma.

The second big wave came after 1985, when the economy was crippled under General Ne Win’s Burmese Way to Socialism, causing shortages of daily necessities. Chinese were able to facilitate border trade in those products. During her fieldwork, Olinga-Shannon said Chinese immigrants who arrived in Myanmar during that period often spoke metaphorically of coming for the “space”, by which they meant less competition and more opportunities.

“The Chinese are known for their entrepreneurship and risk taking, and it was easy to cross the borders,” said Olinga-Shannan, adding that policies at the time encouraged trade with China.

In their paper, published last year, Olinga-Shannon and Farrelly, director of the ANU Myanmar Research Centre at the Australian National University in Canberra, concluded that the Sino-Myanmar borderlands facilitated illegal activity but also through illicit means helped the Myanmar government and citizens subvert the Western sanctions imposed after 1988.

Olinga-Shannon said she has observed that the most recent migrants from China are seeking investment opportunities and do not intend to seek permanent residency.

Not all are seeking opportunities in business, though. Since he crossed the border, Aung Kyaw Oo has relied on a combination of street smarts and learning and understanding local culture. Soon after arriving in Myanmar he sought refuge in a monastery and ordained as a monk.

“I spent one year and four months living in a monastery. It was one of the toughest periods of my life – and I used to be in the People’s Liberation Army,” he said, recalling that life as a monk included two meals a day and long hours in prayer and meditation. The other monks did try to ask about his origin, but they never insisted, he said.

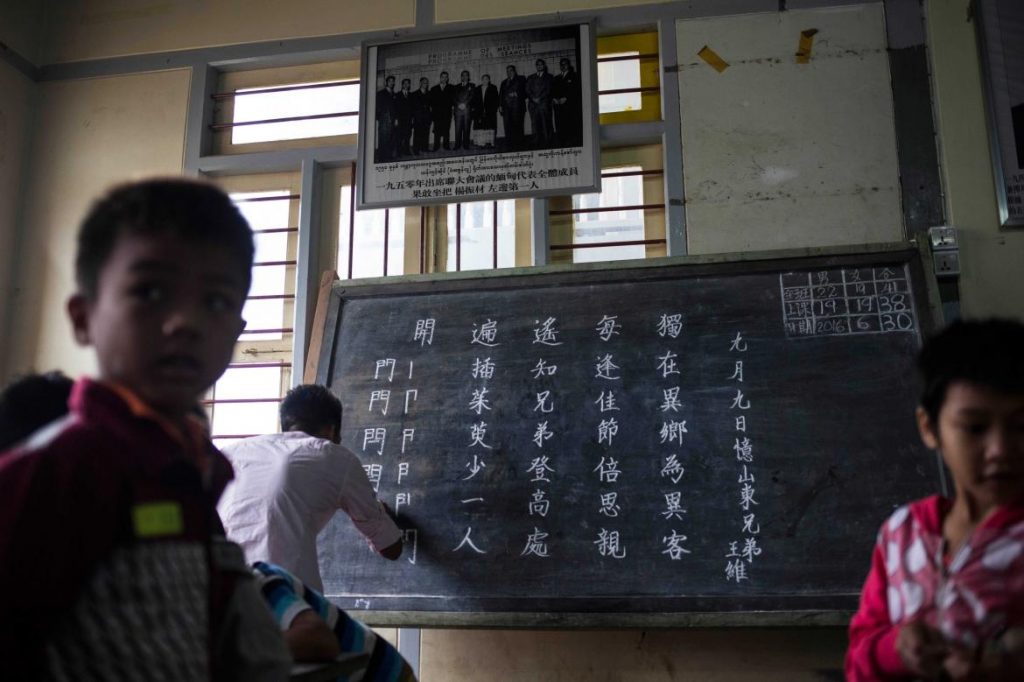

After leaving the monastery he travelled to Mandalay, where he enrolled in Myanmar language classes and worked as an apprentice in a Shan tofu restaurant for years. Through a widening circle of connections, he eventually found a stable job at a Chinese language school, where half the teachers were Sino-Burmese and the other half from China.

“I just want to live a quiet life with books to read,” said Aung Kyaw Oo, who has a BA in history from a university in China.

Ann Wang / Frontier

He almost always dresses in a light blue shirt that forms part of his uniform at work. He keeps a low profile in Myanmar and acquired an ID card describing him as an associate citizen six years ago.

“It cost K40,000,” he said, and was obtained with the assistance of a Sino-Burmese contact at the Immigration Department.

Ms Jayde Roberts, the author of Mapping Chinese Rangoon, Place and Nation among the Sino-Burmese, said the movement of Chinese, particularly Yunnanese, back and forth across a “fluid” border makes it difficult to track who is a long-term resident and who is eligible for citizenship.

In particular, she points to the work of political scientist U Maung Aung Myoe, who has undertaken detailed and considered analysis of ethnic relations in Mandalay and Shan State.

“If you look at Myanmar’s citizenship law, most Sino-Burmese didn’t take it too seriously. Citizenship laws have not been enforced consistently and before the anti-Chinese riots of 1967, many didn’t see how they could benefit from having Burmese citizenship. This has to be understood within the context of how most people in Burma, regardless of ethnicity, are wary of the government. So my question is, people who got the fake identity cards, what is their motive and what are they coming to Myanmar for?” said Roberts, a lecturer in Asian languages and studies at the University of Tasmania.

Ann Wang / Frontier

Her research found that Chinese coming to Myanmar after the 1990s for investment do not need citizenship because they can tap into native place-based and other guanxi-type networks to develop contacts with Burmese citizens. Roberts questions the veracity and pervasiveness of reports about mainland Chinese nationals acquiring fake ID cards through ethnic minority groups such as the Kokang and Wa.

She referred to research by Maung Aung Myoe that found there was significant confusion about who is or is not Chinese. Long-term resident groups such as the Akha, Wa or Kokang are seen as definitely different and probably Chinese.

“In my book I argue that citizenship in Myanmar is very problematic and for people of so-called Chinese heritage or ethnicity, a double-edged sword,” Roberts told Frontier. “Citizenship does not provide them with guaranteed rights. In fact, when they travel abroad, their Myanmar passports are a source of embarrassement and shame.

Officials in Hong Kong, China and Taiwan look down on the Sino-Burmese when they shown their Myanmar passports. Acquiring citizenship is supposed to protect your rights, but in Myanmar it doesn’t,” she said. “For a Chinese person to get a fake identity card to access Myanmar, I think that is a story that really needs to be questioned. Or rather there are individual cases, but do they constitute a trend?”

For many years, the centre of the teacher’s life has been a school deep in the heart of the Chinese quarter of a town in northern Shan State. He wakes at 6am to participate in the prayers that mark the start of the school day.

After a long lunch break the pupils will return to their classes in government schools. As a book lover, he is happy to be in charge of the school’s library. Along with other teachers and students who live at the school, he observes a 9pm curfew. He has been living this way for years.

Ann Wang / Frontier

When he rides his motorbike through the neighbourhood, he often has to make multiple stops for those who greet him as a teacher. He has a friendly relationship with the owners of shops where he buys necessities. He rarely visits other shops and almost never travels to other cities. He knows that keeping a low profile is essential if he wants to stay in Myanmar.

“Race is such a sensitive issue; there is a real anti-immigration sense in Burmese policies that can really flare up and become violent,” said Olinga-Shannon. “The case with the Chinese people is less problematic compared to the Rohingya, but the riot against the Chinese in 1967 was so brutal it’s basically why people stopped speaking Chinese at home.”

“The sense that there will be riots again, that something will happen, remains strong within the Chinese community in Myanmar,” she added. “There is too much nationalism, too much fear of being flooded, we see this in Australia as well and across Southeast Asia. The fear of being flooded with the Chinese is what is driving these policies. However, it is easier now to cross the border legally compared to before.”

Asked why he had never returned to China, Aung Kyaw Oo said he did not see the point because he assumed both his parents had died.

“The place where you can feel the most at ease is where you should call home,” he said.

*Some names have been changed.