Civil society groups and the Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise are striving to raise safety awareness about the possibility of leaks from oil and gas pipelines that can have devastating consequences.

By HTUN KHAING | FRONTIER

IT WAS a Sunday evening in late October 2010 and Sayadaw U Teikthara was in the storeroom of his monastery at Aiggyi village, in Magway Region’s Pakokku Township, gathering candles to distribute to the crowd of devotees waiting outside.

The villagers wanted the candles to participate in ceremonies marking Thadingyut. Also known as the Festival of Light, it celebrates the end of the three-month period known as Buddhist Lent and is one of the most important events on the Buddhist calendar.

When the sayadaw emerged from the storeroom most of the villagers had vanished. They were disappearing into the darkness, running in the same direction. The sayadaw decided to follow them.

The villagers were heading towards nearby Nyaung Hla village where an oil pipeline linking the Thargyi Taung and Ayadaw fields had burst, covering a field with the black, inflammable liquid.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Hundreds of people had already gathered at the site, scooping up the precious oil in buckets to resell.

Suddenly, the sayadaw was knocked down by a massive explosion.

“A big cloud of smoke rose into the sky with a boom,” the sayadaw recalled.

“The explosion set people on fire and they were running madly at random; it was a like a scene from doomsday,” he said.

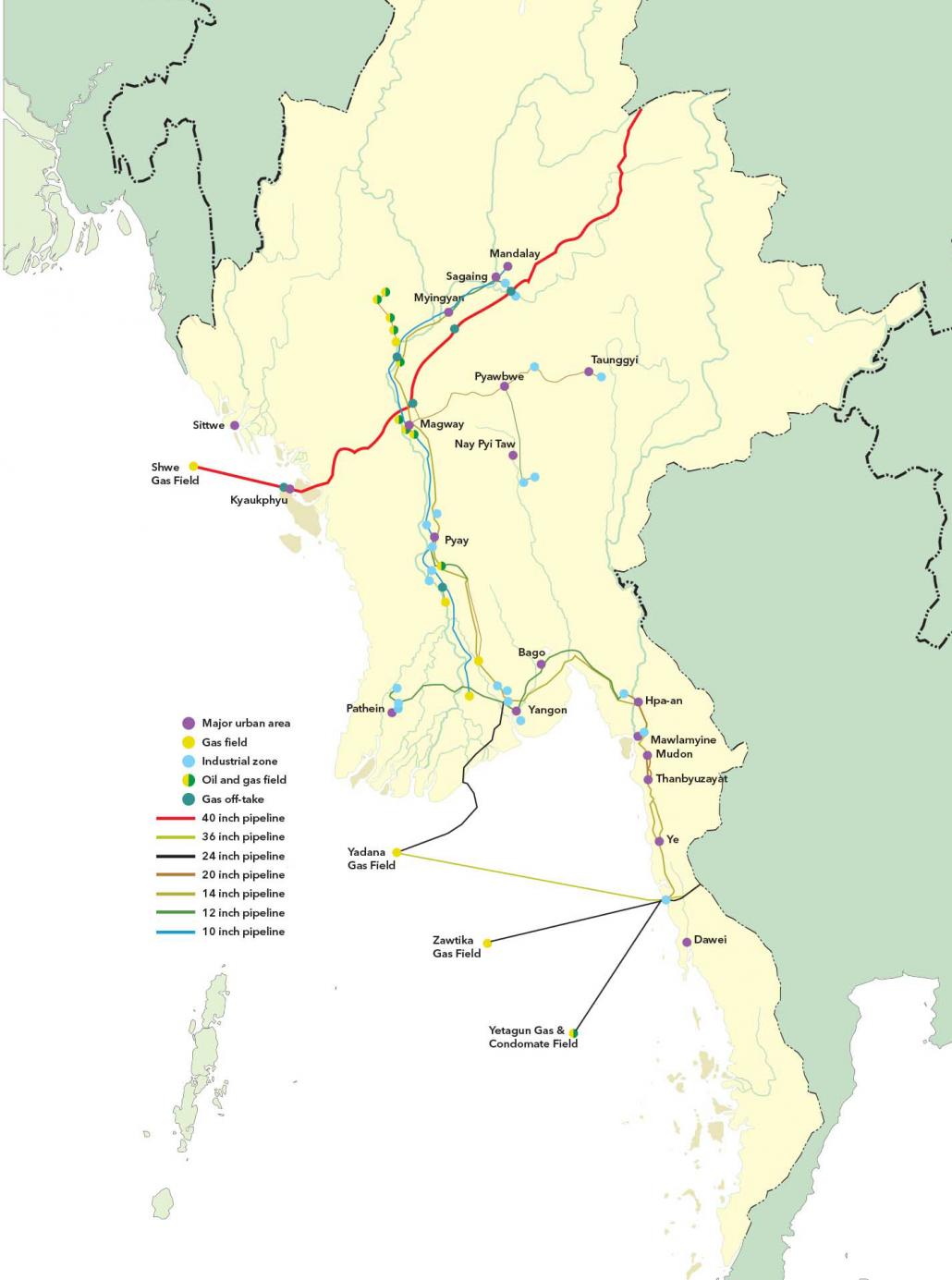

Magway Region is home to many of the country’s onshore oil and gas fields – and an extensive network of pipelines. (Theint Mon Soe aka J | Frontier)

Media reports said the blast killed 14 people and another 121 people were burned, but local residents and firefighters who attended at the scene put the death toll as high as 400.

Some of the reports quoted villagers as saying the government-owned pipeline was in poor condition and badly maintained.

Among the survivors of the explosion was U Kyaw Swe, 54, who lost an eye in the incident and spent two months in Pakokku Hospital recovering from his burns.

Kyaw Swe had rushed to gather oil in the hope that reselling it would help him escape from poverty.

Along with many of those killed and injured, he had seen a news report about villagers salvaging 10 barrels of oil from a burst pipeline and selling them for K120,000 each.

Around Aiggyi village, it was not easy to earn K1,000 a day.

In similar incident in November 2012, a train transporting oil exploded near a village in Sagaing Region’s Kanbalu Township and injured about 90 people, including 25 who were fatally burned, official reports said.

Civil society groups say the government and oil and gas companies need to do more to educate the public about the risks posed by burst pipelines.

People living near pipelines need to learn how to respond if there is an explosion, said U Thant Zin, from the Ayeyarwady West Development Organisation.

The group monitors activity in the oil and gas sector, including the condition of pipelines, on the west bank of the Ayeyarwady River.

“If there is a leak, people scoop up the oil and try to sell it because they are very poor; we need to let the people know how dangerous it is,” Thant Zin said.

“Telling the people that action will be taken against them if they scoop up leaked oil is not enough,” he said.

“When the government says it will inform the people, it might issue a letter, but the information won’t spread among the public,” said U Ye Thein Oo, spokesperson for the Myanmar China Pipeline Watch Committee.

The issue has regularly been raised in the national parliament by lawmakers. In 2014, U Tun Aung Kyaw, the Pyithu Hluttaw representative for Ponnagyun in Rakhine State, told the Hluttaw that he believed the Myanmar-China gas pipeline was in a very dangerous condition between Ann Township in Rakhine State and Padaung Township in Magway Region.

However, Deputy Minister for Energy U Aung Htoo rejected the criticism and said the ministry regularly tested pipelines to ensure they meet international safety standards.

“We have response teams for emergencies and natural disaster. We also plan to train local people every two years in how to respond to an explosion. If we need to we will do the training every year,” he said.

myanmar_map_energy_infograph.jpg

State-owned Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise is also taking steps to raise awareness about the issue. It has issued a pamphlet warning the public against building on or within 15 metres (50 feet) of a pipeline, and growing large trees or burning rubbish near a pipeline.

“Most of the people are lacking knowledge about oil and gas pipelines,” said U Hla Win Htay, general manager of MOGE, Yangon Region.

“When people see an oil and gas pipeline leak they should report it to the local authorities; they must not try to collect the oil because it’s very dangerous,” he said.

Hla Win Htay acknowledged that some pipelines built in the 1990s were of poor quality but could not be replaced yet because of budget constraints.

The problem is a particularly concern in Yangon’s outer western Shwepyithar Township, where MOGE has estimated that more than 1,000 squatters are living on gas pipelines supplying energy to the area’s many factories.

Media reports said three people were hurt in Shwepyithar in February last year after an explosion in a tea shop that had opened on top of a gas pipeline.

This article originally appeared in Frontier’s special report on Myanmar’s energy sector. TOP PHOTO: U Kyaw Swe was badly burned and lost an eye in an explosion in 2010 at a leaking crude oil pipeline in Pakokku Township, Magway Region. Like others in Aiggyi village, he had rushed to the pipeline to salvage oil. (Theint Mon Soe | Frontier)