It’s time for us to embrace the idea that you can wear a beard, kurta or hijab, and have a Muslim name, and still be fully Burmese.

By THAN TOE AUNG | FRONTIER

ONE OF Burma’s most prominent monks, Sitagu Sayadaw, once observed that Muslims are “guests” and Buddhists are “hosts”, and that “the guests must obey the hosts”. Similarly, I have heard Buddhists say that Muslims in Burma (a name I use in preference to Myanmar) need to respect Buddhist culture and “assimilate” into it.

They would also say that Muslims who had embraced Burmese culture and did not wear beards, kurtas, and hijabs were well respected in society. “Some of them do not even have Muslim names,” I was told. People have sent me social media posts or articles that support their conclusion that the more integrated Muslims are into Burmese culture, the less discrimination they will encounter.

These claims need examining.

First of all, the process of integration and assimilation in Burma has always been a one-way street. When Buddhists talk about “Burmese culture”, what they actually mean is Bamar (or Burman) Buddhist culture; Buddhists are the “hosts” of the country whereas Muslims are “outsiders” who came from elsewhere. This places the onus on Muslims to integrate.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

In reality, Muslims – similar to other ethnic minorities – have been forced to assimilate because of the Burmanisation policies of former military governments. Burmanisation has included restrictions on non-Buddhist religious practices and non-Bamar cultural traditions; granting Buddhism special privileges and building pagodas even in non-Buddhist areas; and making Burmese the mandatory language in schools.

Secondly, there is a misconception in Burma that having a Muslim name and wearing a beard, kurta or hijab is inherently foreign. While it’s true that some Burmese Muslims do not wear beards or have Muslim names, many do. Among the nine martyrs assassinated with General Aung San on July 19, 1947 was Abdul Razak, known as U Razak, who was a minister in the pre-independence interim government. Another close associate of Aung San was U Raschid, a prominent student activist during the pre-independence era who later held several ministerial positions in U Nu’s post-independence government.

Razak and Raschid are both Muslim names, and these did not make either of those men any less Burmese. In fact, their struggle for a free and independent Burma makes them truer patriots than today’s self-proclaimed myo chit (nationalists), whose objective is Bamar Buddhist supremacy rather than the wellbeing of all citizens.

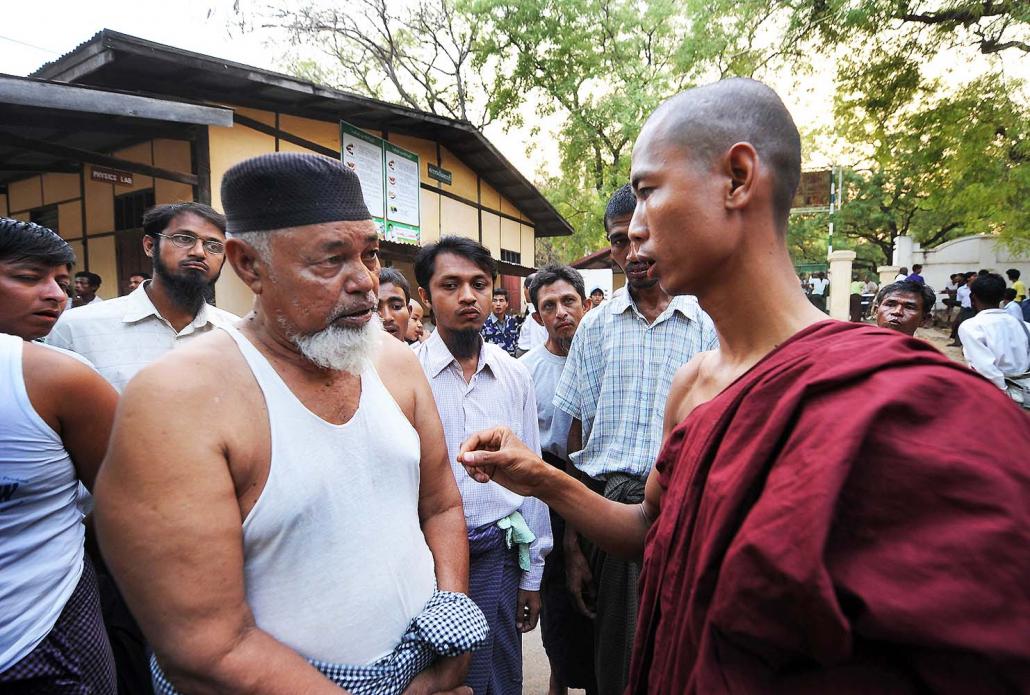

A Buddhist monk speaks with displaced Muslims taking refuge in a school in Meiktila in the aftermath of communal rioting in 2013. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

It’s worth asking why Bamar Buddhist culture is conflated so heavily with Burma’s national identity when there is a great diversity of languages, cultures and religions in Burma, and when so many non-Buddhist and non-Bamar people contributed so positively to its history. Furthermore, so much of what makes up “Bamar Buddhist” culture comes from overseas.

Buddhism, after all, originated not in Burma but in the Indian subcontinent. Gautama Buddha was born in what is today Nepal and gained enlightenment in what is now India. He would have had a similar complexion, and the same ethnic heritage, as people who are branded in contemporary Burma as “foreign” and called kalar, a derogatory term for Muslims and people of South Asian descent.

This racist slur is found in 8th and 10th grade history textbooks used in government schools, which refer to conflict between Buddhists and Muslims during the colonial era as the “Kalar-Bamar conflict”. The textbooks also refer to Chettiars, a Hindu caste group who migrated from southern India during the colonial era, as “Chity Kalars”.

The arguments used by Bamar Buddhist nationalists conform to a well-established ideology of exclusion that can be discerned across society and government institutions.

Sitagu Sayadaw used the same line of reasoning as my middle school teacher when she told me that Burma was a Buddhist country and that I should go back to kalar pyay (“kalar country”) if I could not assimilate into Buddhist culture; and as my high school teacher when she made me sit in a back corner of the classroom for months because I refused to put my palms together like a Buddhist when she entered the classroom.

The notion propagated by former military governments, that to be Burmese is essentially to be Bamar and Buddhist, helped inform such behaviour. The phrase amyo batha thar thana, meaning “race and religion” – the rallying cry of the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, a Buddhist nationalist group better known by its Burmese acronym Ma Ba Tha – is straight out of government high school history textbooks. The textbooks explain how the Young Men’s Buddhist Association was founded during British colonialism to work for “race and religion” – namely, the Bamar race and the Buddhist religion.

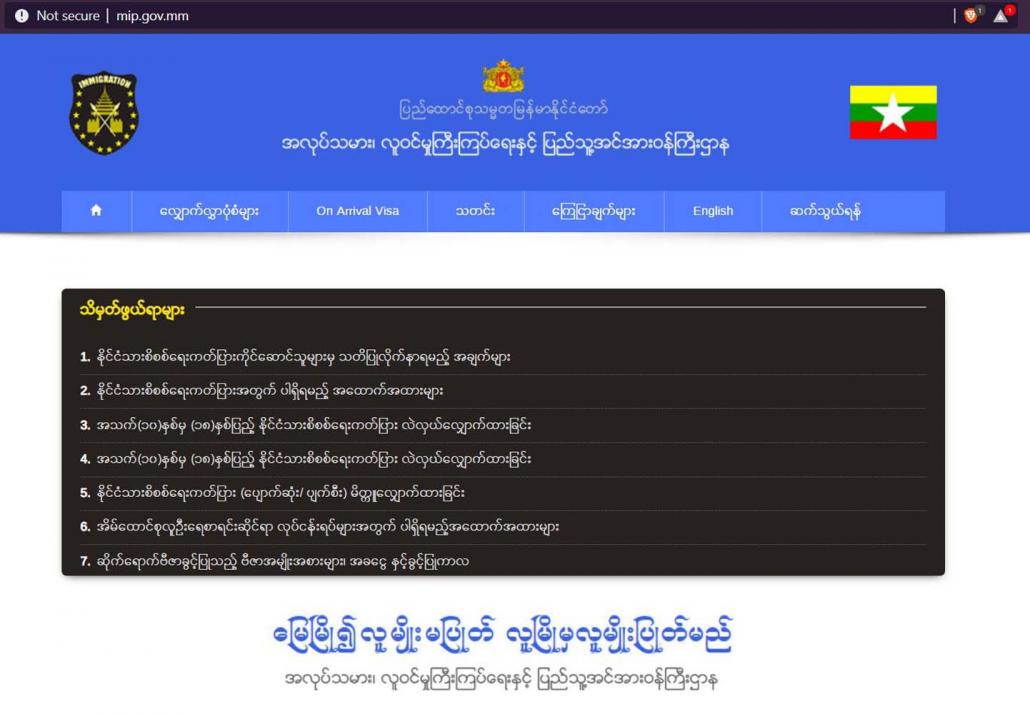

Immigration offices that issue citizenship cards generally display a Burmese slogan that translates as, “The earth will not swallow a race to extinction but another race will.” These words, which also appear on the Burmese language website of the Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population, serve as a reminder to immigration officers that they must take extra care when issuing citizenship cards to Muslims and anyone of South Asian or Chinese descent.

The website of the Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population with the slogan “The earth will not swallow a race to extinction but another race will” in bold blue text.

It also reminds these particular applicants that they will always be regarded as alien no matter how many generations of their family have lived in the country, and that their right to citizenship and Burmese-ness should always be scrutinised.

From all this, we can see a double standard whereby Muslims are blamed for “not assimilating” while at the same time being deliberately “othered” and cast as permanent outsiders, regardless of how much they have done to integrate into Bamar culture.

There are notably fewer complaints about other minority groups, such as the Kachin, Karen and Chin, not assimilating into “Burmese culture”. These ethnic groups have also been the victims of cultural violence – alongside recurrent physical abuse at the hands of the Tatmadaw, which I don’t intend to downplay – but they have consistently resisted Burmanisation policies and maintained their own cultures, religious practices and languages. However, instead of decrying their “failure to integrate”, Bamar Buddhists tend to fetishize their cultures, calling their traditions “cute”, their dresses “beautiful” and their character “innocent and naïve”.

In contrast, Bamar society tends to characterise Muslim culture and traditions as undesirable or even savage. For example, Buddhist friends have often told me they regard the way that Muslims slaughter cows, goats and sheep as “cruel and barbaric”. When I challenge them by asking if they eat meat, they reply, with peculiar logic, that they only eat “dead meat”, meaning the meat of animals that either died naturally or were slaughtered by other people (including other Buddhists).

From a young age, we are taught that Burma officially has 135 ethnic groups and eight major ethnicities in the form of the Kachin, Kayah, Karen, Chin, Bamar, Mon, Rakhine and Shan. We are taught that these groups unanimously joined forces, fought against the British colonialists and founded independent Burma with “pyidaungsu [union] spirit”. The reality was completely different. The leaders of some of these ethnic groups initially did not wish to be part of Burma after independence, being wary of Bamar domination. They only consented to join the union in 1947 after receiving pledges of administrative autonomy for their regions and the option of secession after 10 years, as contained in the Panglong Agreement and the constitution drawn up that year.

But beyond misrepresenting the stances of officially recognised groups like the Karen and Kachin, the military’s version of the nation’s history, which continues to be the official version, largely ignores the longstanding presence and contribution of Muslims.

The limited portrayal of Muslims has always been negative, whether in the government’s history textbooks, the media or society at large, and is based on the narrative that Muslims are “others” who came to Burma, in contrast to the 135 ethnic groups have been present “since time immemorial”. In actual fact, Muslims have been living in what is now Burma since the time of the pre-colonial Bamar and Rakhine kings.

The popular narrative is seemingly ignorant of the fact that more than 140 ethnic groups were once officially recognised, including “Chinese Muslims”, a term that indicated the Panthay, a community of Sunni Muslims from China who settled in Burma in the 19th century. Along with several other groups, they were arbitrarily excluded from the reduced list of 135 that was drawn up to accompany the 1982 Citizenship Law.

Dr Myint Th

This is not to endorse the listing of “official” ethnic groups, whether the list be 135 or 143, but to demonstrate the arbitrariness of the current list, which is held up in Myanmar as a fact that has held true throughout history. Ethnicity, as anthropologists have shown, is a fluid social construct. It is not the government’s job to decide which people do or do not constitute an “official” ethnic group; it should be left to every group to decide how they want to identify, and they should be recognised accordingly.

By excluding large numbers of people who were born in Burma, the list of 135 creates a hierarchy between recognised and unrecognised groups and reduces Muslims to being second-class citizens whose Burmese-ness is continually under suspicion.

This is demonstrated by how hard it is for Muslims who are legally eligible for citizenship to receive formal identity documents. Muslims, and others of South Asian and Chinese descent, have to line up in a separate queue at the passport office in Yangon to be interrogated about their “mixed blood” by an official who often demands a bribe. Even the Kaman, who are the only Muslim group among the list of 135, have to submit to such treatment when they apply for a passport.

Even when they receive citizenship cards, Muslims are reminded that they are not “full” citizens in the eyes of the government. The cards often denote their “race” as being Indian, Pakistani or Bengali, marking them as being of foreign origin, even if their families have lived in Burma for multiple generations.

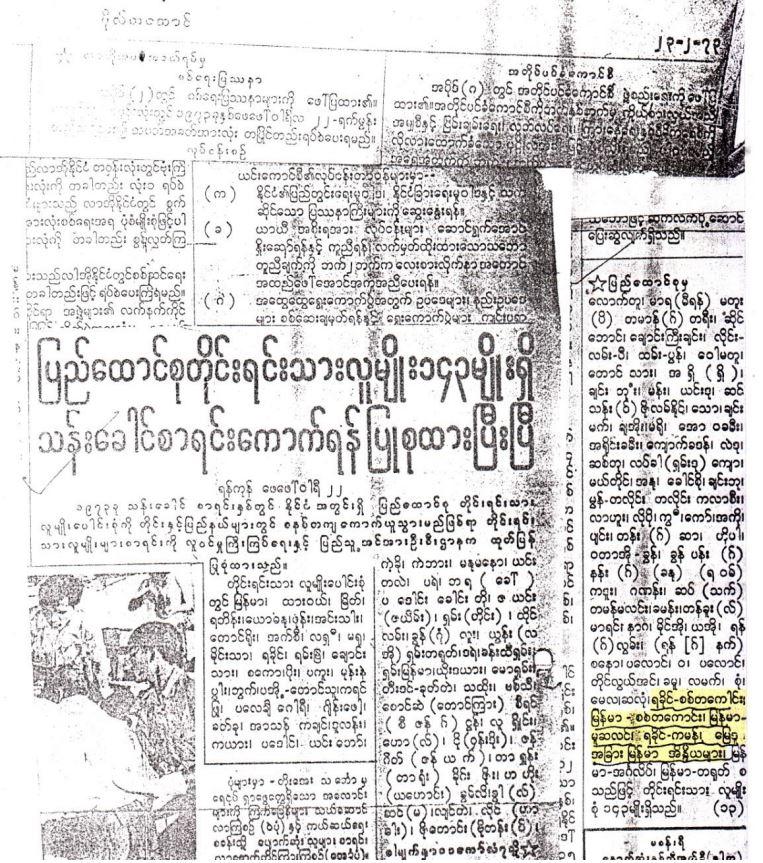

At the passport office in Yangon, where Burmese Muslims and people of South Asian and Chinese descent – whom officials classify as being of “mixed-blood” – must form a separate queue and receive greater scrutiny. (Than Toe Aung | Frontier)

Meanwhile, extraordinary Muslim politicians, scholars and intellectuals have been victims of an official Bamar-washing of Burma’s history, meaning that few in the country are aware of the contributions they have made to our society. When school children are taught about the struggle for independence, they learn overwhelmingly about Aung San, a Bamar, while the significant roles played by leaders such as Mahn Ba Khaing (a Karen), Sao San Tun (a Shan) and Muslims such as Razak and Raschid are rarely mentioned.

Few schoolchildren are taught that the famous teakwood U Bein Bridge near Mandalay was built by a Burmese Muslim official of the same name, who was in the service of the Bamar king in the mid-19th century; or that the U Shwe Yoe and Daw Moe Dance, now a treasured Burmese festival dance performed to traditional music, was invented by a Burmese Muslim actor known as “U Shwe Yoe” who starred in films and plays in the early 20th century. It’s likely that the legacy of U Ko Ni, a constitutional expert and legal adviser to the National League for Democracy who was assassinated outside Yangon International Airport in January 2017, will also be forgotten.

While letting these figures fade into obscurity, the government continues to erect statues of Aung San in ethnic regions despite objections and active resistance from local populations. There has been no corresponding effort to honour ethnic leaders, let alone Muslim ones.

To sum up, it’s clear that even when Muslims do integrate into Bamar culture and society, they continue to be discriminated against and marginalised – and their achievements are destined to be left out from official history and popular memory. It’s therefore time for us to discard our prejudices and stop deciding who can or cannot be regarded as a citizen of Burma based on a person’s religion and ethnic background.

It’s time to create a national identity that can include everyone born and living in Burma, regardless of the religion they practice or the clothes they wear. It’s time for us to embrace the idea that you can wear a beard, kurta or hijab, and have a Muslim name, and still be fully Burmese.