Ill-treatment is rife, the food is bad and hygiene is sub-standard in the infamous Yangon prison that has long been the butt of grim word-play humour about “going insane”.

By OLIVER SLOW | FRONTIER

“There’s only one word for what life was like inside Insein prison – hell.”

U Kyaw Soe Win spent six years in the notorious jail on Yangon’s northern outskirts when Myanmar was under military rule. He was arrested in 1992 for protesting against the National Convention. After what he said was a sham trial lasting a few days, during which he had no access to a lawyer, he was convicted under the Emergency Provisions Act.

“I spent twenty three hours a day inside my cell; I was allowed out just three times a day, for twenty minutes at a time,” said Kyaw Soe Win. “I didn’t experience physical torture, but spending that much time inside your cell without anything to read or write, that is mental torture.”

Asked about the quality of prison food, Kyaw Soe Win laughed.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“It was the lowest quality food, not nutritious at all. Low quality rice, maybe some beans and a bit of vegetable – if you could call it that,” he said.

Ko Letyar Tun, who spent two stints in Insein, including many years on death row, over his involvement in the 1988 national uprising, said the quality of life depended on who was the head jailer.

“If you had a good one, life wasn’t too bad, but if you had a bad one, it was a horrible place to be,” Letyar Tun said. “I don’t remember the name of who was in charge when I arrived, but I can tell you, I will never forget his face,” he said.

Letyar Tun said torture was common in Insein.

“I was beaten by hand, with a stick. They beat you a lot. But it didn’t matter if you told them the truth. They heard what they wanted to hear, and if they didn’t like what you told them, they just carried on beating you,” he said.

Colonial relic

Glance from your plane window as it arrives or takes-off from Yangon International Airport and you might catch a glimpse of Insein, easily identified by its size and distinctive shape.

Insein prison was built by the British in 1887 to relieve overcrowding at Rangoon Central Gaol, at the western end of Commissioner’s Road (now Bogyoke Aung San Road).

A scale model of Insein prison at the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners museum in Yangon. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

Insein is said to have been built in the circular Panopticon design developed by the 18th century British philosopher and social theorist, Jeremy Bentham. The design was aimed at enabling a single guard to monitor all inmates without them knowing if they were being watched.

Bentham once said the use of the design for prisons enabled them to function “as a mill for grinding rogues honest”.

Critics of the design said it was inhumane and Insein has acquired an infamous reputation, mainly because of the effect on inmates of a lack of hygiene and the regular use of torture, especially when the country was under military rule.

Over the years, Insein has held thousands of political prisoners, many of them students and other activists arrested during the 1988 national uprising and the monk-led protests in 2007 known as the Saffron Revolution.

Political prisoners continue to be held in Insein.

The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners said the nation’s jails held 36 political prisoners in May, with another 57 in custody awaiting trial and 169 granted bail.

A jailer’s perspective

U Thein Win spent 16 years with the Corrections Department including two stints at Insein, where he began working as a warder in 1975. He later worked as a warder at Myitkyina, Kawthaung and Mandalay prisons, before returning to Insein as chief jailer ahead of the protests in 1988.

Thein Win said he went four days without sleep or food during the height of the unrest, when a constant stream of arrested protesters was being delivered to the prison.

As a prison official, he regularly received death threats and carried a pistol for his protection.

“I didn’t feel pride about my work, but I had a sense of duty,” Thein Win told Frontier. “I felt a big burden, but I had to be loyal to the government. I had to do my job even though we faced death threats.”

Thein Win was vague when asked if he had been involved in torturing inmates but said he had often seen prisoners being beaten. Some of the worst beatings he saw were inflicted on the student leader, Min Ko Naing, and the comedian known as Zarganar.

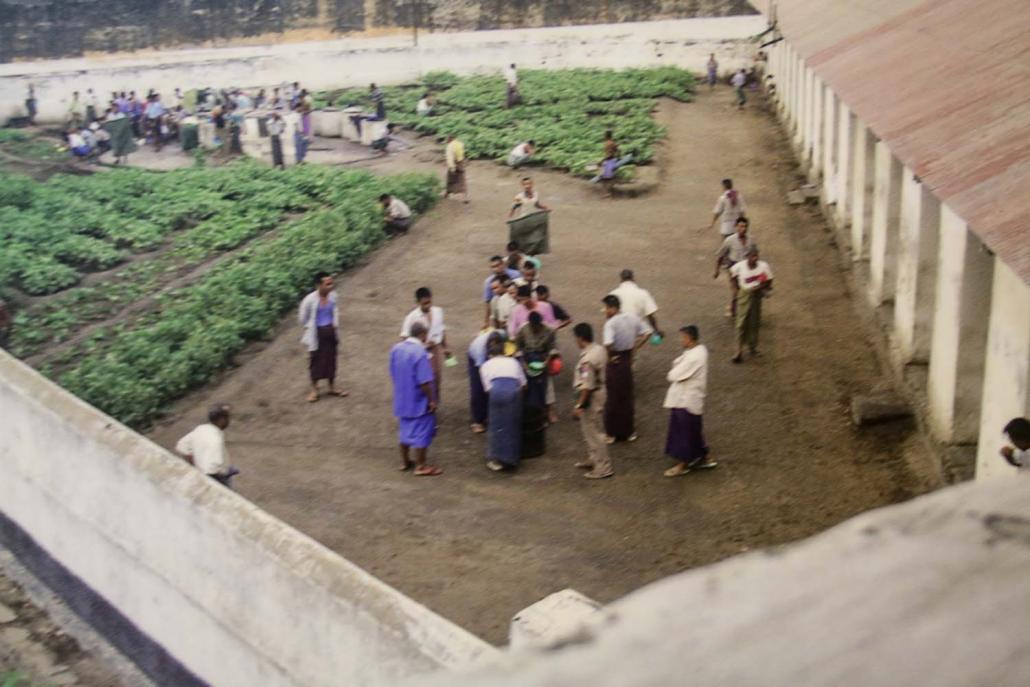

Photo taken from inside the prison, courtesy of AAPP.

However, it was an incident more than a decade earlier that made a bigger impression on his mind: the execution of student activist Salai Tin Maung Oo, who was hanged at Insein on June 25, 1976.

Tin Maung Oo had gone underground after participating in the student-led protests that erupted after the body of former United Nations secretary-general U Thant was returned to Burma from the United States in December 1974. The activist was arrested in Yangon on March 22, 1976, after returning for celebrations the next day marking the 100th birthday of Thakin Kodaw Hmaing, one of the greatest Burmese poets, writers and nationalist leaders of the early 20th century, who died in July 1964.

Tin Maung Oo, the only student activist to have been formally executed under junta rule, was defiant to the end. The authorities had offered to spare his life if he agreed to abandon political activism and admit that the protests he was involved in were wrong, but he refused.

Tin Maung Oo’s last words to his executioners were: “You can kill my body but you can never kill my beliefs and what I stood for. I will never kneel down to your military boots!”

Speaking more than 40 years later, Thein Win said he could never forget what he saw that morning. As he spoke, tears filled his eyes.

“At about 4am, soldiers came to his cell and began beating him,” he said. “They gagged him and eventually dragged him to the room where he was hanged.”

Thein Win, who held the role of chief jailer for several more years, said the treatment of many prisoners made him feel ashamed.

“At first I was proud to work as a government official, but afterwards I felt ashamed,” he said, although he expressed pride in trying to help many inmates, and said some still came to his house to pay him respect.

A foreigner’s experience

One of Insein’s most high profile foreign inmates in recent years was New Zealander Mr Phil Blackwood, the general manager of a bar in Bahan Township.

Blackwood and two Myanmar colleagues, the bar’s owner, U Tun Thurein, and its manager, Ko Htut Ko Ko Lwin, were arrested in December 2014 and sentenced the following March to two-and-a-half years in prison for insulting religion over the online use of a Buddha image to promote a drinks promotion night. The trio was released from Insein in January 2016.

A family member of a political prisoner demonstrates outside Insein prison in 2016. (Ann Wang | Frontier)

Blackwood’s trial attracted considerable attention, and as a “high priority” prisoner he said he had his own cell.

“The first few months were tense,” Blackwood told Frontier in a recent phone interview from New Zealand, where he lives. “When I first went inside I was told there could be a potential hit on me, so I took that pretty seriously and mostly kept to myself.”

Blackwood said he gradually adjusted to life in prison and his situation became more bearable after he began to form friendships, including with some of the guards.

He was able to spend about eight hours a day outside his cell, in the jail’s exercise yard.

The doors of his cell were opened twice a day, from 7am to 12pm and from 2pm to about 5.30pm. The two hours they were closed were when “high risk” prisoners could go outside, Blackwood said.

Psychological victories helped to keep his spirits up, and one was to refuse to leave his cell as soon as the guards opened it and to return well before he was due to be locked-up again.

“It might seem silly, but that really helped me to feel that they weren’t in control of what I was doing. I felt like I could decide what I was doing,” Blackwood said.

There were dark moments, too. Blackwood said he never saw any inmate being tortured, but he did observe a rapid deterioration in the physical condition of a middle-aged man over about a week that coincided with a visit of a group he labelled the “Gestapo”, after the ruthless secret police of Nazi Germany. Frontier was unable to establish who this group was.

“We really saw him go downhill quickly over that week or so,” Blackwood said. “The guy had been inside for something like 13 years, then suddenly he deteriorated to the point where we heard he had died,” he said.

“It was hard in there, even for someone who, I guess, is in relatively good shape. But this guy didn’t look healthy, and the heat and the stress must have taken a toll.”

Photo taken from inside the prison, courtesy of AAPP.

His family were visiting from New Zealand at the time of the incident, and during a meeting with them he had to ask his wife, siblings and mother to leave the room, so he could speak with his father alone.

“I said to him, look. If anything happens to me in here, just make sure my body goes back to New Zealand,” he said.

“But you get used to anything, I guess.”

Blackwood was contemptuous of the way his trial was conducted.

“If I was to say they would need to change anything, it would be that bit before the prison – the trial, if you can call it that. It’s a shambles, and everyone inside that prison has to go through it,” he said.

The need for reform

For about three months, Blackwood and his co-defendants were ferried between Insein and the Bahan Township court once a week for a trial that attracted considerable media attention.

There’s been greater domestic and foreign media interest in the pre-trial hearings of Reuters reporters Ko Wa Lone and Ko Kyaw Soe Oo, who have regularly been making a shorter journey from Insein to Insein Township court.

They have been in custody since being arrested in Yangon’s northern outskirts on December 12 last year while investigating a massacre of Rohingya in Rakhine State and are accused of breaching the Official Secrets Acts, for which the maximum penalty is 14 years’ imprisonment.

The reporters, who are alleged to have been in possession of confidential documents, have appeared in court more than 20 times since the hearings began. The case has been marked by some dramatic revelations, including testimony by a police officer that their arrest was a set-up.

One issue in dispute is where they were arrested. The prosecution maintains that the documents were found in their possession when they were stopped by a routine police patrol. The reporters have told their families they were arrested soon after leaving a restaurant to which they were invited by police who handed them some documents.

Reuters journalist Ko Wa Lone, who is currently serving time inside Insein prison alongside his colleague Ko Kyaw Soe Oo. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

The pre-trial hearings have also been told by an officer involved in the arrest that he burned his notes about the arrest and another prosecution witness said he had written details of the case on his hand because he was “forgetful”.

In April, Police Captain Moe Yan Naing testified that a senior officer had ordered his subordinates to plant confidential documents on Wa Lone to “trap” him. Moe Yan Naing has since been jailed for one year for violating police discipline. The day after he testified, his family was evicted from government housing in Nay Pyi Taw.

Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo have not commented on their treatment in Insein, but Reuters quoted defence lawyer U Than Zaw Aung as asking Police Captain Myint Lwin at a hearing on June 11 if the pair were “not allowed to sleep” while they were under interrogation for three consecutive days after their arrest last December.

Than Zaw Aung also asked the witness if Kyaw Soe Oo was “forced to kneel down” on the floor for more than three hours during questioning.

Myint Lwin denied the reporters were deprived of sleep or made to kneel, saying officers under his command were not allowed to “do such a thing”.

He also denied, under cross-examination, that the reporters were sent to a specialist interrogation facility after their arrests, saying they were initially detained at a police station in northern Yangon.

Ko Bo Kyi, a former political prisoner, and founder of AAPP. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

Reuters reported that Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo told reporters outside the court after the hearing that they were questioned every two hours for about three days after their arrests by different officers who asked if they were “spies”.

Wa Lone said it was “completely untrue” that they had remained in a regular police station.

The treatment of the pair was “mental and physical torture,” Khin Maung Zaw told Reuters after the hearing, adding that evidence gathered through such methods was unlawful and should not be presented in court.

Meanwhile, campaigns continue for the release of political prisoners.

“The issue of political prisoners is not finished inside this country,” said U Bo Kyi, a former political prisoner and founder of AAPP. “The government needs to do more on this issue,” he said. “Prisoners are human beings; they must have enough space, they must have enough nutrition, they must have enough medication. They must not be dehumanised. The government has responsibility for that.”

Bo Kyi said the penal system urgently needs reform and one of the first measures should be to reduce the prison population by establishing the rule of law and ensuring that anyone charged with an offence receives a fair trial.

“Everything is interlinked, so it has to be holistic. It must include institutional reform, police reform and judicial reform,” he said.