A walk through Yangon’s Chinatown on the weekend offered little sense of an impending crisis.

Fruit vendors lined the street, taxis revved and honked, young couples walked hand-in-hand, and the outlines of distant high-rises were smudged by air pollution. The changes were scattered and easily missed. Latha Township’s popular Cherry Mann kebab shop only offered takeaways, but in the next-door teashop customers were wedged shoulder-to-shoulder, sharing snacks.

Little by little, though, life is ratcheting down in the commercial capital. Since the weekend, township authorities have ordered takeaway-only service from restaurants, while the Circular Railway is slashing services and the Shwedagon pagoda is open for reduced hours. As businesses shed staff and migrant workers return to their villages, fearing the sudden imposition of travel restrictions, the normally crowded streets are thinning out.

Compared to much of the world in the age of COVID-19, this no doubt sounds like business as usual. Even as confirmed cases of the viral disease have gradually climbed since the first two were announced late on March 23, the Myanmar government has been squeamish about imposing tough measures. Though international arrivals are halted, people can still travel fairly freely throughout the country, turn up to work at their offices, and enjoy happy hour beers at a range of bars still eager for business.

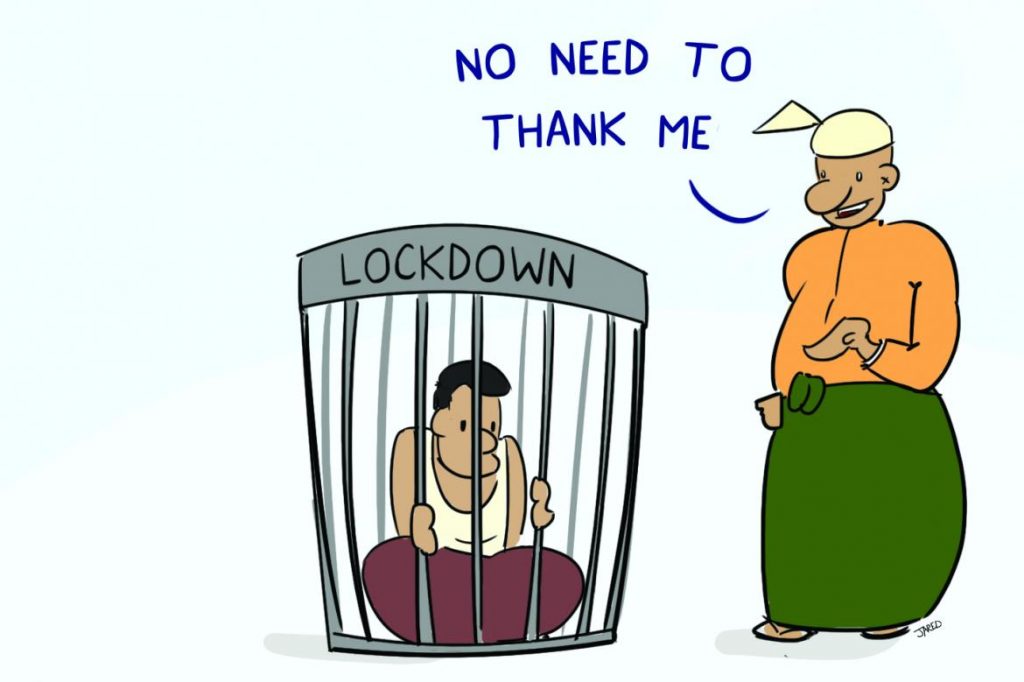

For many, this squeamishness is perceived as a cavalier disregard for the lives of the Myanmar people at a time when governments elsewhere have imposed stringent lockdowns to slow the virus, despite the dire economic consequences. Combined with the miniscule number of tests for the virus that have been conducted (375 at press time), this has prompted some analysts to conclude that the government is in denial about the danger posed by the virus. Ill-judged comments by high-level officials about Myanmar’s reserved cultural norms acting as a barrier against infection have fed this perception, as have defensive reactions from citizens to foreign individuals and entities who have pointed to a looming disaster.

But the weekend walk through Chinatown revealed something else: everywhere, on the pavements, in the streets and inside shops, were people living hand to mouth, feeding their families and meeting other expenses through the cash earned that day. If they seemed indifferent to the risks of the virus, that’s because business-as-usual was all that was keeping them from financial ruin – a fate that, with Myanmar’s lack of a social safety net, is arguably worse than infection with COVID-19.

A rigidly enforced lockdown that lasted weeks or even months would be devastating, leaving millions out of work and with no savings or support. Without a radical reorientation of government towards welfare provision, Myanmar would be adding an economic and social catastrophe to a possible public health emergency. The cruel scenes playing out across India during its countrywide lockdown should not be re-played in Myanmar.

However, such a reorientation is sadly unrealistic within the window of the pandemic. The Myanmar state, though large, is hugely inefficient, and even the best-willed administration would struggle to reach the millions who don’t have bank accounts, work informal and undocumented jobs, and move frequently. And though the nation’s natural resources generate vast wealth that could transform any response to a crisis, most of it is tightly sequestered by men with guns, beyond the reach of civilian planners.

In the rich world, lockdowns are being debated in terms of “saving lives” versus “saving the economy”. In Myanmar, it’s not so simple. Myanmar’s unjust political economy would take years of sustained effort to unravel. Today, as coronavirus infections climb, the elected government is left with only bad options.