After two years languishing in camps in Bangladesh, young, educated Rohingya are finding expression through writing… and demanding a say in decisions about their future.

By CLARE HAMMOND | FRONTIER

Photos VICTORIA MILKO

KUTUPALONG — Rohingya poet Ro Anamul Hasan hurries along the congested footpaths that connect the bamboo shelters in Camp 8-East, in the world’s largest refugee settlement at Kutupalong in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Temporary homes and other structures extend to the horizon in every direction at the Kutapalong camp. Daily queues for basic necessities begin growing in the early morning and the heat is exhausting, despite the monsoon haze.

“Except for our shelters, we have nothing here,” says Hasan, as he ducks into an airless room that contains just a table and six chairs. “We belong nowhere.”

Hasan started writing poetry in 2015, the year after he matriculated from high school in northern Rakhine State’s Maungdaw Township. “I was not allowed to attend university because I am a Rohingya,” he told Frontier.

Denied a job in the civil service, he was left with time to spare. He filled it by reading widely, including books by Myanmar author Kaung Thant, whose work he regrets he cannot acquire in the camp.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

In late 2016, his writing took on a new sense of urgency. His grandfather was shot dead by Tatmadaw soldiers, he said, and four of his uncles were arrested and imprisoned. By August 2017, he was fleeing a military campaign of murder, arson and rape, along with 740,000 other Rohingya Muslims from northern Rakhine.

Leaving his dog behind, Hasan took a small boat across the Naf River to Bangladesh. “When we reached the bank, my foot became stuck in the mud,” he said. “It seemed in the mud I felt a hand, and when I held it [I realised it was a] dead body. I was very scared inside.”

In Myanmar, Hasan had been called a Bengali and an immigrant. But in Bangladesh he soon realised he would face discrimination because he was Rohingya.

“So, where did we come from?” he asked. He said he thinks about this every day. “There is no advantage to being a human in our community. The world doesn’t value us… me.”

He explained that he sees poetry as a powerful way to express these feelings, and to amplify the voices of the Rohingya community. He is one of a small but growing group of poets who write under the mentorship of Mayyu Ali, an established writer.

In March, Mayyu Ali founded the Art Garden Rohingya Facebook page, which has already published more than 150 young poets, who write in both Myanmar and English.

Some of these poems were published in July, in I am a Rohingya, the first anthology of Rohingya poetry to be published in the English language.

In mid-August, Mayyu Ali told Frontier by telephone that one reason he wanted to foster a community of young poets was to help channel the frustrations of young people who have been stuck in the Bangladesh camps for two years, with no access to formal education, and no immediate prospect of returning home.

The United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, said in an August report that without adequate education, young people in the camps can fall prey to drug dealers and human traffickers. Others, including the International Crisis Group, a think-tank, have warned that the lack of formal education could lead to criminal activity and even radicalisation.

“So many bad things are happening [in the camps], and I really worry,” Mayyu Ali said. “I don’t want them to think of knives and guns to put in their hands. I want to divert that attention into literature, poetry and art. I want them to be addicted to those peaceful things.”

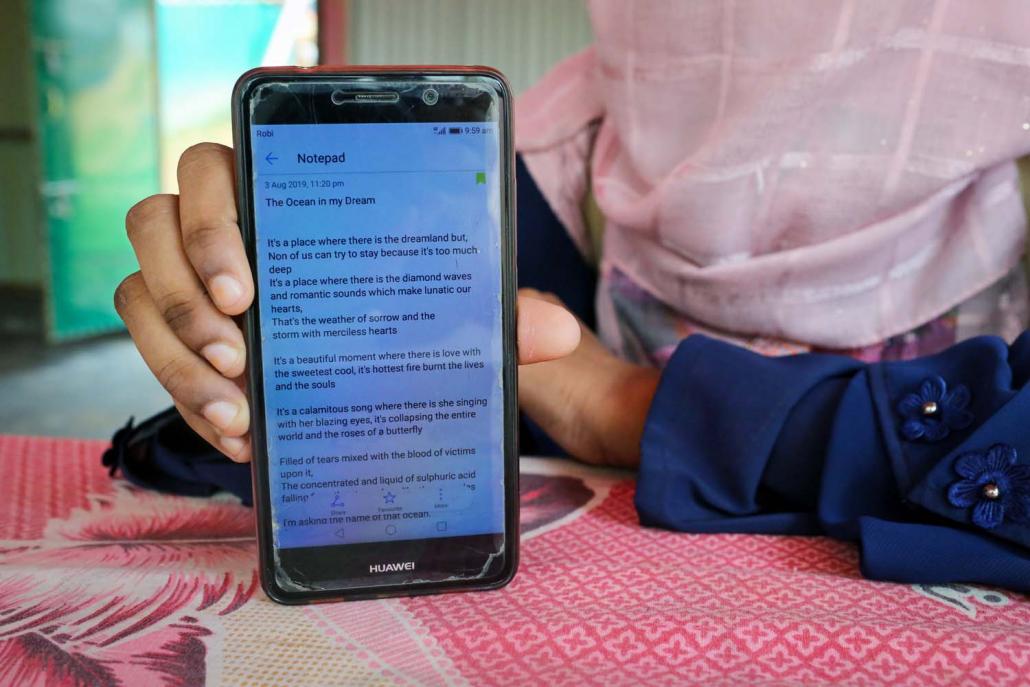

A young refugee shows a poem on her phone on August 6. Written just days earlier, it was her first attempt at poetry. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

‘So many problems’

In a simple room at the edge of the Kutupalong camp, a group of Rohingya youth leaders are sitting in a circle on plastic chairs, and discussing how they see themselves. Some identify as educators, others as activists, poets, singers, dancers, or Facebook users.

These young men and women are part of an organised Rohingya civil society that has been able to develop in Bangladesh, in a way that could not have been possible in Myanmar. The initial chaos of the refugees’ arrival in Cox’s Bazar made organisation difficult, but after two years there is a degree of stability in the camps and the community is increasingly finding its voice.

Among those in the room is a woman named Lucky, who works for both the Rohingya Women Solidarity Network and the Rohingya Women Empowerment and Advocacy Network.

She meets every Friday and Saturday with other women who are defying conservative Islamic traditions by leaving their homes to do volunteer work. Some Rohingya women working for NGOs have faced threats from within their community because of their work.

Lucky told Frontier that Rohingya women face “so many problems”, the most pressing of which include gender-based violence and child marriage.

Rohingya women and girls often face harassment and abuse in the camps, especially at night, while child marriage for girls remains a major risk, UNICEF said in its August report.

The US State Department has said that traffickers prey on Rohingya women and girls to sell them into the sex trade in Bangladesh and abroad.

“First we need to remove child marriage, and then we can remove violence, because so much violence comes from child marriage,” Lucky said.

She believes that many of the issues faced by Rohingya women stem from a lack of education. A lack of education opportunities in Myanmar means that about half of the refugees have not had any formal schooling, and many more have only attended religious schools.

In late 2017, humanitarian agencies and NGOs set up learning centres for refugees in Bangladesh and by June 2019, UNICEF figures show that non-formal education in Myanmar and English had been provided to 280,000 children between the ages of four and 14.

But learning centres mainly offer informal lessons and playtime, because the Bangladesh government has prohibited formal schooling for the refugees. An estimated 97 percent of refugees aged 15 to 18 are not receiving any education at all.

Education for girls lags even further behind, UNICEF said in the August report.

“In most cases, when girls reach puberty they are withdrawn from school by their families. Surveys suggest that changing this longstanding practice will be very difficult,” it said.

The Kutupalong camps in Cox’s Bazar comprise the world’s largest refugee settlement. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

‘Standing on our own feet’

UNICEF has spent millions of dollars developing curriculum materials for the refugees known as the Guidance for Information Education Program (GIEP). The UN agency has received permission from the Bangladesh government to implement the programme’s levels 1 and 2, which are designed for children.

But Rohingya educators told Frontier they had not been consulted about the GIEP.

They said they strongly prefer using the Myanmar curriculum, because they see their future as being in Myanmar, and it would improve their ability to reintegrate.

“The Myanmar curriculum is very important for us, because it is our native country and our mother language,” said Salah Uddin, a former headmaster of Kyein Chaung high school in Maungdaw Township, who fled Myanmar two years ago.

He has since established the Rohingya Pioneer High School of Kutupalong, which enrolled more than 300 students in 2018 and teaches the Myanmar curriculum, but operates informally, lacks basic funding and depends on volunteers.

“So many dollars are donated by the World Bank and others, but they only open learning centres and teach kindergarten education,” he said. “The [Bangladesh] government and NGOs are not helping us. We are standing on our own feet to help the poor refugee children.”

A report published in July by the Peace Research Institute Oslo, a think-tank, surveyed refugee-led networks of community teachers comprising 373 teachers educating 9,848 children. The report, We must prevent a lost generation, cited many respondents as expressing concern about the lack of consultation with Rohingya education leaders by the education sector and policymakers.

The report said this was particularly problematic because Rohingya refugees viewed education as an important component of their greater struggle for human rights and citizenship.

“The government education system was the key way in which Rohingya children were exposed to the Burmese language, learned about Myanmar history, and engaged with their peers from other ethnic groups despite the rising inter-communal tensions in their midst,” it said.

Denying refugees access to the Myanmar curriculum stripped them of this connection to their homeland, Salah Uddin said. “If anyone denies teaching the curriculum, he is committing a crime against humanity.”

There is a risk that unless humanitarian agencies consult refugee leaders on the new curriculum, they could reject it and the issue could become a flashpoint for renewed tensions between camp leaders and humanitarian agencies, the PRIO report said.

Tensions have risen in the past about refugee policy decisions with political implications that were undertaken without adequate consultation, it said, most notably over the move by UNHCR and the Bangladesh government in 2018 to issue identity cards.

This resulted in a refugee-led boycott of the card, culminating in a camp-wide strike.

Mohib Ullah, leader of the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights (standing, right), holds a meeting with other refugees on August 4 to discuss their preconditions for repatriation. (Victoria Milko | Frontier)

‘Just shouting’

One of the strike’s organisers was Mohib Ullah, leader of the Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace and Human Rights, which has become one of the leading refugee-led advocacy groups in the camps. Sitting outside a bamboo shelter that serves as the ARSPH office, Mohib Ullah says he is frustrated.

Two years after the military crackdown of 2017, he says that endless rounds of interviews with journalists, human rights groups and diplomats are going nowhere.

“We are shouting, shouting, shouting, just shouting,” he said. “Nobody is listening to our voice. It’s a very bad feeling. Last year we were sad, but this year we are angry a lot.”

His grievances are echoed in a poem entitled “A Rohingya refugee visits the zoo” by Mr Azad Mohammed, which was published by an online news service, Rohingya Today, on August 10.

“Journalists arrive, ask us to re-live the trauma./They screen us for TV, win awards,” he wrote. “Diplomats speak to us in our most formal tents/They assure us they hear us,/Then never come back.”

Employees of UN agencies and NGOs, as well as diplomats, privately acknowledged to Frontier that Rohingya refugees have not been adequately consulted on decisions about their future.

They said that part of the reason was concern about the extent to which emerging organisations represent the Rohingya community as a whole, as well as a lack of representation for women.

Mr Marin Din Kajdomcaj, UNHCR’s head of operations in Cox’s Bazar, said that “it took time for all of us, including refugees, to look into the representative structures” within the Rohingya community.

It also took time for the Rohingya to organise themselves into civil society networks and to “build capacity to identify issues and be part of decisions” he said.

The biggest decision that Rohingya refugees want to be part of is repatriation. Although the Myanmar government claims it wants the Rohingya to return to Myanmar, it still refuses to recognise them as an ethnic group, or grant them citizenship.

Mohib Ullah told Frontier on August 4 that he expected dialogue with the Myanmar government would precede repatriation, because this was agreed during July 27 talks between Rohingya representatives and Ministry of Foreign Affairs permanent secretary U Myint Thu.

“We are not staying a long time in these places,” he said, referring to the camps. “We are preparing for dialogue with Myanmar, and then we will go back.”

But just two weeks later Myanmar and Bangladesh announced that repatriation would begin on August 22, potentially dashing hopes of dialogue, and prompting impassioned criticism by Rohingya activists. “Myanmar is lying everywhere everything,” youth activist Mr Mohammed Nowkhim wrote in a statement shared on messaging service WhatsApp.

Despite anger over the suffering inflicted by Myanmar government forces on the Rohingya community, all of the civil society leaders who spoke to Frontier said they wanted to return home as soon as possible, on the condition that their repatriation demands were met.

Ro Khin Maung, 24, founder of the Rohingya Youth Association, which promotes education for young people, said he dreams of standing in elections in Myanmar and becoming an MP, although he did not expect this would be possible until the military-drafted 2008 Constitution is amended.

“I am upset when I see harsh words calling me a Bengali. I am not Bengali. My country is Myanmar,” he told Frontier. “I want to be a proud citizen of my country, but we must be accepted as full citizens.”

State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is unlikely to accept the Rohingya’s demands ahead of the 2020 election for fear of political blowback, he said, citing the National League for Democracy’s decision not to field any Muslim candidates in the 2015 general election.

“Because of this I do not think the crisis will be solved until the 2020 election. Within this time there will be nothing happening for our community,” he said.

Even so, he said that Rohingya youth leaders would continue to advocate peacefully for their right to return freely to their places of origin. “We are not a state enemy,” he said. “We are a community and society which belongs to Myanmar.”

Additional reporting by Victoria Milko