While there is no quick fix to Yangon’s chronic traffic problems, dedicated bus lanes and incentives for cycling could help get people moving again.

By SEAN FOX | FRONTIER

ACUTE TRAFFIC congestion in Yangon is not just annoying – it is bad for the economy and for the health of the city’s citizens. Workers waste time and money getting to and from their jobs; companies waste time and money moving goods through the city; and idle vehicles crawling through downtown streets spew pollutants into the atmosphere that contribute to debilitating respiratory illnesses.

How did things get so bad and what can be done about it? This is the question I sought to answer through a recently concluded research project funded by the International Growth Centre, a research centre based at the London School of Economics and Political Science in partnership with the University of Oxford.

Traffic is a good sign

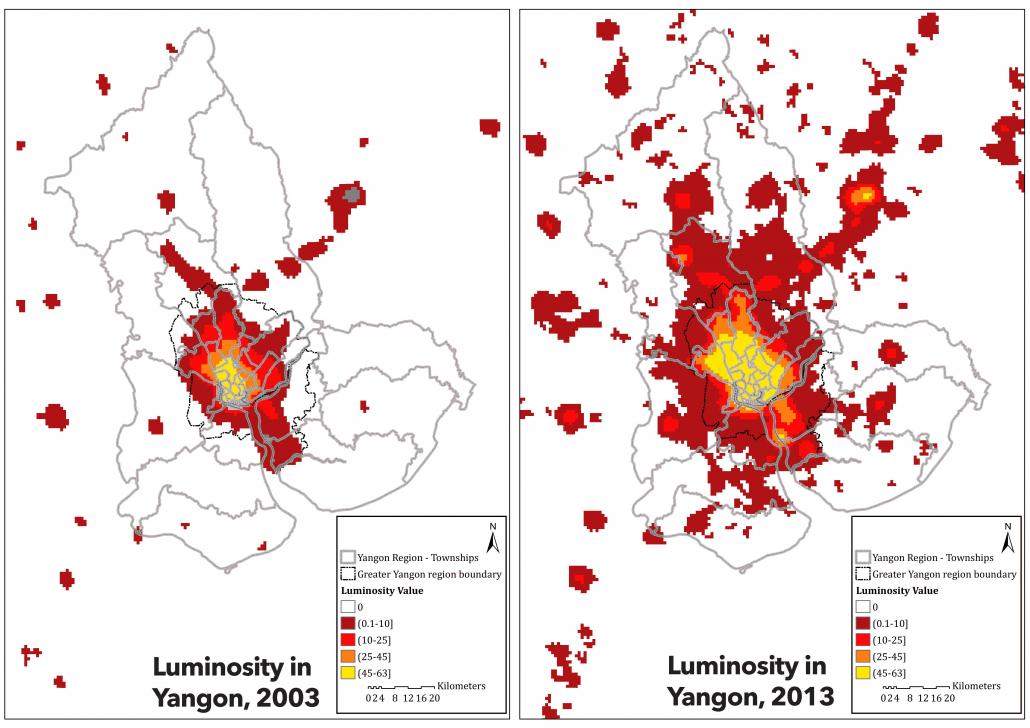

In some ways, bad traffic is a good sign: it reflects rapid economic growth over the past decade. To get a sense of just how fast the city’s economy has been growing we looked at satellite images of the city at night. These images are increasingly used by economists to measure economic change in places where robust economic data is lacking. This is done by measuring changes in luminosity – that is, how much light is being emitted from an area – which is closely related to changes in economic output. Simply put, more light means more economic activity.

class=

The dramatic growth of Yangon’s economy is illustrated above, which show images of Yangon Region at night in 2003 and 2013 respectively. Over this period the level of luminosity nearly tripled, which we estimate translates into an impressive average annual growth rate in output of 8.5 percent. And growth appears to have been accelerating: between 2008 and 2013 we estimate that growth surged to an average rate of 11.2 percent per annum.

This roaring growth has been accompanied by an explosion in the number of cars on the city’s roads, particularly since vehicle import restrictions were relaxed in 2011. With vehicle prices falling and traffic getting worse, Yangon’s burgeoning middle class jumped at the opportunity to buy cars and escape the deteriorating bus system. Official figures indicate that there was a 153 percent increase in registered vehicles in Yangon between 2011 and 2014 alone.

The congestion spiral

While economic growth and increased access to cars are both good things, the combination has set in motion a “congestion incentive spiral” in which worsening traffic creates incentives for people to behave in ways that worsen traffic.

Prior to 2011 buses were by far the dominant mode of transport. But the bus system was run as a competitive cartel, with a restricted number of private bus owners competing for passengers on similar routes. This system incentivised overcrowding, reckless driving and underinvestment in bus fleet maintenance in the quest for profits. All of this contributed to congestion and a miserable experience for passengers.

Against this backdrop, those who can afford to buy a car to commute have increasingly been doing so. A personal car is certainly more comfortable, but also – crucially – always quicker than using the buses. The ability to go direct from origin to destination, without stops or transfers, significantly reduces overall journey time.

But there is a catch: As more people choose to drive their own cars traffic becomes worse for everyone, which encourages more people to ditch the buses in favour of car transport. This congestion spiral can only be broken by dramatically increasing the costs of individual car use or providing an attractive alternative to lure people out of their cars.

It’s not just a traffic problem

Unfortunately, there isn’t really any alternative to buses and cars in central Yangon due to a legacy of poor urban planning and underinvestment. Indeed, there has been no significant investment in public transport infrastructure since the colonial era, when the city’s circular railway was built. This circular railway is still used, of course, but it carries a very small fraction of Yangon’s daily commuters.

This lack of alternatives highlights the fact that Yangon is suffering from something worse than bad traffic: Yangon is facing a mobility crisis. What does that mean exactly?

“Mobility” refers to the ability of people to get around easily, and people can move through cities in many ways – not just in cars and buses. While all large cities suffer from traffic congestion, many do not suffer from mobility crises because other options are available: bus rapid transit systems that are insulated from traffic; cycling infrastructure; rail networks; and pedestrian-friendly mixed-used developments that reduce the demand for vehicular journeys.

In Yangon traffic congestion and reduced mobility are intrinsically linked due to a lack of alternatives to cars and buses, but this could change with relatively modest investments and policy reform. Two priorities stand out.

First, plans for a proper bus rapid transit (BRT) system were announced in 2014 but subsequently shelved, with the fleet incorporated into the Yangon Bus Service. This is a mistake. Proper BRT systems have dedicated lanes for buses that cannot be used by private automobiles. They are, in effect, immune to traffic and as a result can be a very appealing alternative to private cars. Indeed, from Bogota to Bristol and Johannesburg to Jakarta, BRT systems have proven to be a very cost-effective means of increasing urban mobility. Reviving Yangon’s BRT plans – including the creation of dedicated lanes, at least at peak times – should be a priority.

Second, the relatively flat topography of Yangon is very conducive to cycling, yet bicycles are banned downtown. Relaxing restrictions on the use of bicycles on key arteries and in the city centre, combined with modest investments in cycling infrastructure, could provide a very affordable mode of individualised transport and rapidly increase mobility.

In short, thinking about the problem as a mobility crisis encourages us to look for diverse ways to get people moving through the city again, not just in their cars.

The need for governance reform

But introducing a proper BRT and supporting the growth of cycling in Yangon will not be sufficient to ensure mobility in the long run. Yangon is projected to formally join the ranks of the world’s megacities, defined as those with at least 10 million inhabitants, by 2030. With this growth comes physical expansion, which will alter commuting patterns and increase transport demand.

What Yangon desperately needs is a comprehensive and financially viable transport plan developed and implemented by an independent public transport authority with a metropolitan remit. At present, city-wide planning is largely undertaken by foreign firms and organisations. The delivery of city infrastructure and services is fragmented across three tiers of government and dozens of agencies and offices. The lack of locally led planning coupled with this fragmentation of governance is the true underlying cause of Yangon’s mobility crisis.

While the energetic efforts of the chief minister of Yangon to reform the bus system should be applauded, they will not be enough to get the city moving again. A BRT and more cycling would help, but ultimately a new approach to city governance with an empowered metropolitan authority will be needed. The sooner steps are taken to reform Yangon’s governance the better: The decisions and investments made today have profound consequences for developments in the future. As the city grows it will become increasingly complicated and expensive to upgrade transport infrastructure.

Yangon has the potential to reclaim its historic status as one of Asia’s great metropolises, but it needs integrated, metropolitan-scale governance to do so.

This article draws on the report Tackling Yangon’s mobility crisis: A political economy perspective (IGC, 2017).