Northern Chin State has barely appeared on the radar for most visitors to Myanmar, but a campaign aimed at highlighting its stunning landscape could change that.

By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER

IF YOU visit the brisk mountain town of Falam, Chin State, one of the best travel agents you can find also happens to be the local preacher.

Pastor Thawng Bik serves Falam Baptist Church, a quaint, red-brick structure in the town’s main square, which offers a sweeping view of the valley.

Ask, and Thawng Bik will tell you about Lailun Cave, the fabled birthplace of the very first Chin people, about the remote village of Tashon, birthplace of anti-colonial war hero Con Bik, and the grassy, windswept mountaintop of Buannel, said to be enchanted by angels.

However, these sites are in few, if any, guide books. Nor can one simply organise an official tour. Instead, you will have to ask around for a part-time-translator, or perhaps befriend an English teacher or local NGO worker who is willing to show you around in exchange for a few rounds of whiskey-in-beer with a side of beef jerky (a local favourite).

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“It’s not that difficult [to travel to],” Thawng Bik told Frontier. “You can find things, but there is no tourist industry here.”

Chin State, and its picturesque north in particular, is worth a visit, and is home to an almost untouched land of sweeping ranges, hidden valleys and rustic villages.

But the state has almost no proper hotels, limited mobile phone coverage, and most of its roads are unpaved, winding trails that are prone to landslides during the rainy season. The drive from the nearest airport – in Kalay, Sagaing Region – to the state capital Hakha takes ten hours in good conditions. During monsoon season, the journey can take days.

A modest number of tourists cross the border from India to visit the famous heart-shaped Rih Lake, but the only feature on the radar for most tourists is the wilderness around Mount Victoria, in the state’s south.

The rest is virtually untouched.

Playing to its strengths

The responsibility of enticing tourists to one of Myanmar’s least developed states falls in part to Salai Isaac Khen, Chin state minister for development, industry and tourism.

His strategy? Make Chin’s rugged landscape an asset.

“We are not like Bagan or Inle where the tourists enjoy walking around the pagodas and [boating] on the lake,” he said. “But in Chin State, we have very, very beautiful forests and very, very beautiful mountains.”

Chin’s wilderness rivals the Shan and Kayin hills for mountain biking, trekking, climbing and kayaking, he argued, and areas like Mount Kimo near Paletwa Township or around the upper Kaladan River are virtually untouched in contrast with other adventure sports hotspots in Southeast Asia.

Chin’s poor quality roads and Spartan amenities could be a draw for the tourist demographic that wants to get off-the-grid.

Those promoting tourism in Chin State plan to make use of what the state already has: Tourists can stay with local families, eat local food and experience local culture.

“It is called community-based tourism or community involvement tourism,” Isaac Khen said. “It focuses on enjoying rural life by staying in the villages, receiving tourists in local houses, performing traditional dances, serving the tourists local food… And on the other side the community members benefit by learning from the tourists.”

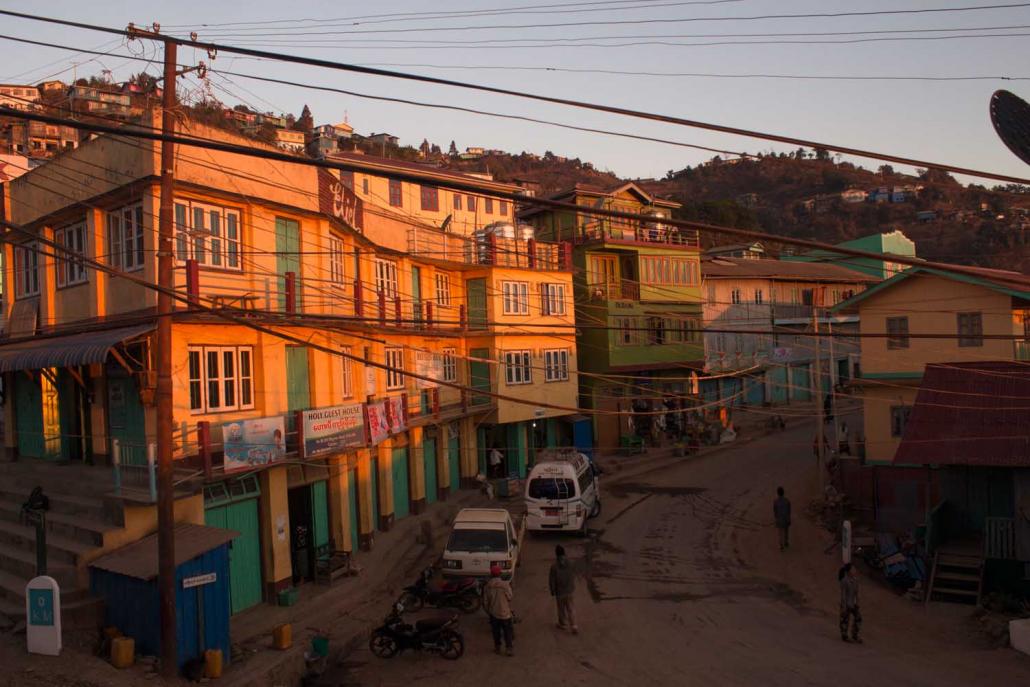

A view of the main street in Falam. (Jared Downing | Frontier)

Isaac Khen drew inspiration from similar community-based tourism schemes in Kachin and Kayah states. He argued that it not only leapfrogs the traditional tourism industry, but it highlights Chin peoples and culture, which is what makes the state so special.

The first government-sponsored CBT project was launched in January, near Lake Victoria in Kanpetlet Township, in partnership with ActionAid Myanmar, and similar projects are being considered for villages in Falam and Tedim townships.

The programme complies with rules against hosting foreigners by designating host homes as “homestays” or “bed and breakfasts,” where a handful of foreigners eat and sleep with a local family in between trekking and mountain biking trips to Mount Victoria.

ActionAid has also been training local people in how to best host tourists, an endeavour that can be more complicated than it sounds.

“Everyone has individual behaviour, and there might be some unexpected risk or [an] insecure situation. Anything can happen,” Isaac Khen said.

But it is equally important that tourists understand their hosts’ culture.

“No one is trained to be a good, responsible tourist,” Isaac Khen said. “But so far we have hardly received reports of tourists significantly misbehaving, but in other parts of Myanmar there are some reported cases of tourists creating misconduct. [But] this is understandable because a tourist is a tourist.

“So as the government and the community, it is an important rule that we are able to provide a safe, responsible tourist environment.”

Concerning hot water

When the United States Ambassador to Myanmar Mr Scott Marciel visited Chin State recently, he did not stay in a proper hotel, but at special “state lodgings” in Hakha that are reserved for distinguished guests, said Salai Amen, a translator and guide in Chin State.

For most visitors though, Amen said one of the only options in the state capital is a basic clean room with hot water and private bathrooms for about US$20 (K27,000) per night.

In other parts of northern Chin there might be guesthouses, but you can forget about hot water or a private bathroom. Amen said travel restrictions in Chin State lasted so long not because of political or security issues, but because the guesthouses were a state embarrassment.

“Some people contact me and ask me how to start ecotourism, but we don’t have anywhere good enough for foreign people to stay,” he said. “There are not even one [star] hotels.”

Amen completed a three-month course in tourism and hotel management at Strategy First Institute in Yangon, but most of his clients are development workers, journalists or politicians. Most of the handful of tourists who come do so for “poverty tourism”, or, as Amen put it, “to react to hardship”.

He agrees with Isaac Khen that there is potential for ecotourism and adventure tourism, and likes the idea of CBT, but believes innovation and novel strategies will bring limited success. He thinks the tourism industry will only gain real traction with regular old luxuries.

“We need at least [three star] hotels,” he said. “Now they don’t even provide breakfast.”

That reality is not lost on Isaac Khen. He said the Chin State government has tried to encourage investment in more and better hotels, and said 12 are currently planned for townships including Hakha, Tedim, Falam and Paletwa, with accommodation levels ranging from budget rooms for backpackers to luxury suits and separate cabins.

How quickly the projects will developed remains to be seen, but Amen believes more needs to be done than just building hotels. They also require reliable power, mobile phone coverage, good quality roads and qualified staff – in short, basic development needs that go beyond tourism.

The “Chin brand”

Isaac Khen said he is optimistic about infrastructure development and expects improved transportation within the next year. However, one of the biggest challenges the area faces in attracting visitors is making people aware of what is there, he said.

The state government is raising funds for online marketing campaigns and plans to partner with the Ministry of Hotels and Tourism and the Myanmar Tourism Federation to hold promotion fairs in Yangon and Mandalay.

But he said these are more about raising awareness that there are in fact things to see and do in Chin State: there are also mountains, rivers and rich culture.

The message is: There are things to do, and you can be among the first to do them.

“These locations are still virgin,” he said. “So I hope the destinations in Chin State will become very well known in the next few years.”

In the meantime, you can still kayak the Kaladan River, climb Mount Zinghmuh, where dead souls are said to pass on their way to the afterlife, and wander the rustic, wood cabins of Chin’s mountain towns.

And if you need advice, just knock on the church door.