A purpose-built camp north of Yangon that over three years housed delegates who laid the foundations for the 2008 Constitution has been abandoned to the forces of nature.

By MRATT KYAW THU | FRONTIER

Photos STEVE TICKNER

THE EARLY years of the 21st century could be exasperating for Myanmar youngsters who wanted to watch their favourite Chinese Kung Fu series on state-run MRTV; for weeks at a time it broadcast blanket coverage of sessions of the National Convention.

The young Kung Fu fans were angry: they wanted action but regarded their only viewing option as boring junta propaganda.

The only possible similarity between the much-interrupted National Convention and a Kung Fu production might be a fussy director who calls “Cut!” too often.

The convening of a National Convention to draft a constitution to replace the suspended 1974 charter was announced in April 1992 by the then junta, the State Law and Order Restoration Council.

dsc_5359.jpg

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Steve Tickner / Frontier

It was 14 years before the on-off convention and a drafting panel completed the task of writing a constitution, in February 2008. The charter was approved in a sham referendum in May that year.

Delegates initially convened on January 1993 at the Ahlone Road compound now occupied by the Yangon Region parliament but most of the convention’s intermittent proceedings took place at the purpose-built Nyaunghnapin Camp in Hmawbi Township, about 45 kilometres north of downtown Yangon.

dsc_5136.jpg

Once an important location for important – and deeply divisive – political decisions, Nyaunghnapin Camp in Yangon Region’s Hmawbi Township has been left to the elements. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

The first session at the camp, from May 17 to July 9, 2004, followed the unveiling by the junta in August the previous year of its seven-step roadmap for a transition to democracy. The first step of the roadmap, which has given Myanmar its first civilian-led government since 1962, called for reconvening the convention. It had been adjourned since 1996.

Broadcasts from the grand Pyidaungsu Hall at the camp showed high-ranking military officers in crisp uniforms, political party delegates in neat white shirts and longyis, and those from ethnic groups in colourful, traditional attire.

dsc_5190.jpg

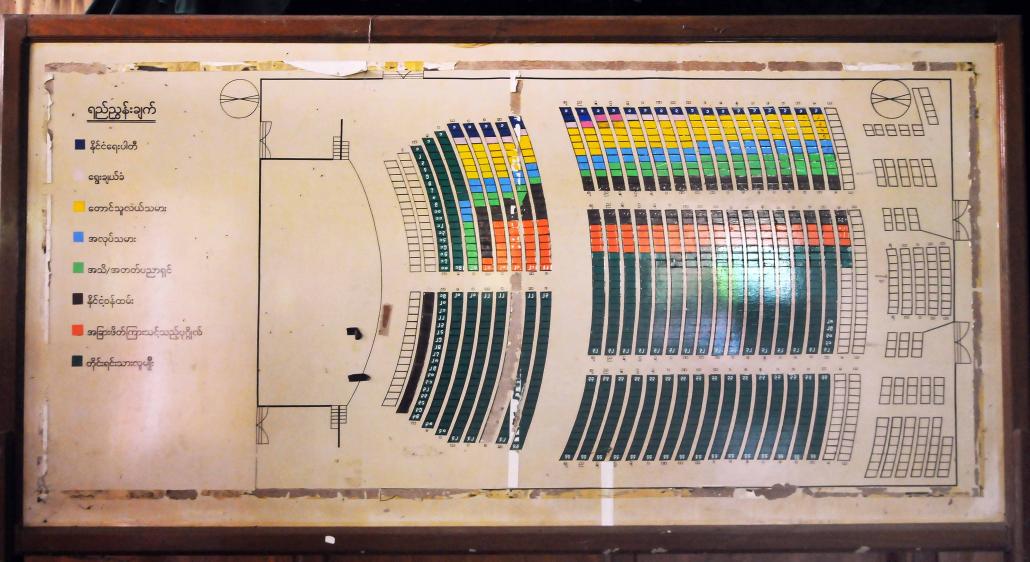

The delegate seating plan at the National Convention building. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

There was much coverage of military officers and other delegates giving long speeches.

The camp, near a village of the same name, is about 10 kilometres from the Yangon-Pyay highway.

For a venue that played an undeniably important role in the nation’s political history, the camp has become a sorry sight.

Once a lively, self-contained community when the convention was in session, it has become a ghost town.

dsc_5121.jpg

A sign at the entrance to the Nyaunghnapin Camp, where the National Convention to draft the constitution was held, is overgrown with leaves. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

A sign on a back gate of the camp compound, which covers more than a square kilometre, warns against trespassing but there are no guards to be seen. Or dogs.

Weeds flourish beside faded pompous grandeur of the Pyidaungsu Hall where the constitution was debated. Shrubbery has almost concealed the mythical, snarling chinthes symbolically guarding the entrance to the building.

The 600 air-conditioners that once helped to keep delegates and others cool are exposed to the weather and sprouting weeds and the clinic and convenience stories are crumbling and overgrown.

The wide, main thoroughfare leading to the hall is being reclaimed by grass and bushes that have already conquered many of the compound’s other roads, along which buses once shuttled between the site’s buildings when the convention was in session.

dsc_5279.jpg

The future of the Nyaunghnapin Camp, which is on state-owned land, is unclear. There have been rumours that it will be sold off, but so far no deals have been announced. (Steve Tickner / Frontier)

The tall lamp-posts along the main road are like the skeletons of dead trees in a desert.

“When the convention was in session, the whole camp would light up the night,” said Ko Sithu Aung, a Hmawbi resident who worked on the project to build the camp as a casual labourer.

Sithu Aung earned K2,000 a day and welcomed the work. “My stomach was wet then,” he told Frontier, using a Myanmar expression that means he was never short of food.

The camp was placed off-limits to civilians in September 2007 after the convention concluded by adopting the fundamental and basic principles of the constitution. The charter was completed by a 54-member drafting commission announced in December that year.

dsc_5216.jpg

Steve Tickner / Frontier

After nearly a decade of neglect, farmers ignore the ban on trespassing and cut grass in the compound to feed to their livestock.

When the National Convention was in session at Nyaunghnapin Camp it housed more than 1,000 participants, who enjoyed air-conditioned accommodation, free meals and a daily allowance of K300.

Entertainment was also provided. The state-run New Light of Myanmar reported on June 6, 2004, that the Entertainment and Welfare Subcommittee of the National Convention Convening Management Committee had arranged a screening in the camp’s gymnasium of “Thamee Maik”, (Naughty Daughter), starring Lwin Moe, Htet Htet Moe Oo and May Than Nu.

In its early years, the National Convention was wracked by upheaval.

Two days after its first session convened in Yangon in 1993, it was adjourned because of dissent from the opposition party and ethnic nationality representatives among its 702 delegates — only 99 of whom had been winning candidates in the 1990 election won in a landslide by the National League for Democracy. Most delegates were township-level officials appointed by the junta.

dsc_5299.jpg

Steve Tickner / Frontier

The convention was suspended in April 1993 after ethnic nationality delegates objected to a proposed centralised political structure. The disruptions irritated SLORC and it created the Union Solidarity and Development Association, under the patronage of junta strongman Senior General Than Shwe, to take a leading role in the convention.

Another suspension followed in September 1993 after ethnic nationality delegates continued to push for a federal system.

In November 1995, after the junta denied a request from the NLD to review the convention’s working procedures, the party’s 86 delegates boycotted proceedings and were expelled.

The expulsion of the NLD delegates led to a walk-out in solidarity by the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy and the Arakan League for Democracy.

In March 1996, SLORC adjourned the convention. In July that year it enacted a law that made criticism of the National Convention illegal and offenders liable to long prison terms.

The convention did not convene for another eight years until it met at the Nyaunghnapin Camp after Prime Minister General Khin Nyunt had unveiled the seven-step roadmap.

U Tun Yi, a central executive committee member of the National Unity Party and a delegate to the National Convention, has fond memories of the camp.

“It was a happy time when we were there,” he told Frontier of the years between 2004 and 2007. “The government provided all the facilities we needed and we participated in the discussions in comfort.”

Tun Yi, whose Socialist-era party had won 10 of the 492 seats contested in the 1990 election, said the security-conscious Than Shwe had chosen the site for the camp because it was in an isolated area near a number of military bases.

“In my opinion, whatever the previous government and the military might have done the camp is the responsibility of the current government to do the right thing. If the compound is not properly maintained it will fall into complete disrepair,” he said.

The amount spent on building the camp must have been considerable. The future of the abandoned compound is unclear.

Yangon Region assembly MP Daw Sandar Min (NLD, Seikgyikanaungto-1) said she was unaware of any plans for the compound. “As far as I know, the government has not sold it but I do not know what the previous government might have done,” she told Frontier.

National Convention timeline

May 27, 1990 National League for Democracy wins general election in a landslide, claiming 392 out of 485 seats.

July 27, 1990 The State Law and Order Restoration Council promulgates SLORC Declaration No 1/90, in which it refuses to hand over power to the NLD and states that those elected in May “have the responsibility to draw up the constitution of the future democratic state”.

April 24, 1992 The SLORC military government announces that a National Convention will be convened to draft the constitution.

May 28, 1992 A National Convention Convening Commission is formed. The committee includes 14 SLORC officials and 28 people from seven different political parties.

July 10, 1992 The National Convention’s 702 delegates are named. Only 99, or about 15 percent, are representatives from the 1990 election.

October 2, 1992 The military government issues SLORC Order No 13/92, announcing the six objectives of the National Convention. The objectives are: non-disintegration of the union; non-disintegration of national unity; perpetuation of national sovereignty; promotion of a genuine multiparty democracy; promotion of the universal principles of justice, liberty and equality; and participation by the Defense Services in a national political leadership role in the future state.

January 9, 1993 The National Convention starts its first session and adjourns after just two days following dissension from opposition and ethnic delegates.

June 7, 1993 Lieutenant-General Myo Nyunt, who heads the convening committee, reopens the convention by stating that the new constitution must guarantee a leading role for Tatmadaw in national politics.

September 16, 1993 The National Convention is suspended again, after ethnic minority representatives continue to propose a federal system.

September 2, 1994 The National Convention reconvenes and discusses self-administered areas, the legislature, the executive branch, and the judiciary.

November 28, 1995 The 86 NLD delegates boycott the National Convention after the authorities reject a request to review the National Convention’s working procedures. They are expelled from the convention the following day.

March 31, 1996 The SLORC adjourns the National Convention following the departure of the NLD representatives.

August 30, 2003 Prime Minister General Khin Nyunt announces the “Seven Step Roadmap to Democracy”, the first of which is reconvening the National Convention, which has been adjourned since 1996.

May 17-July 9, 2004 The National Convention resumes at Nyaunghnapin Camp in Hmawbi Township.

February 17-March 31, 2005 The National Convention conducts another session with 1,075 delegates attending to discuss legislative power sharing.

December 5, 2005 – January 31, 2006 The National Convention conducts another session at Nyaunghnapin with 1,074 delegates. In January, talks focus on the role of the armed forces in the future political system.

October 10 – December 29, 2006 The National Convention sits for its fourth session since 2003.

July 18, 2007 The National Convention resumes for its pronounced final session.

September 3, 2007 The National Convention concludes with the adoption of the Fundamental Principles and Detailed Basic Principles.

December 3, 2007 At a press conference, Minister for Information Brigadier-General Kyaw Hsan announces the first meeting of a 54-member Constitution Drafting Commission.

February 9, 2008 The military junta announces that a National Referendum will be held in May 2008, followed by a general election in 2010.

May 10, 2008 The constitution is overwhelmingly approved at a flawed referendum, with more than 92 percent of votes supposedly in favour. The referendum takes place two weeks later in areas affected by Cyclone Nargis, which hit on May 2-3 and killed almost 140,000 people.

Sources: Human Rights Watch, state media