Vendors of fake medicine and faith healers are using spurious claims to prey on desperate people of limited means who have been diagnosed with cancer and other life-threatening diseases.

By HTUN KHAING | FRONTIER

Travelling home by bus recently I noticed an advertisement for a product that claimed to provide effective treatment for about a dozen diseases, including HIV/AIDS, cancer, and ailments affecting the eyes, bones and muscles.

The advertisement said the product was developed as a result of research conducted in the United States, but no institution was mentioned. I felt uneasy after reading the ad because it reminded me of a friend who died of AIDS about seven years ago.

Due to the stigma related to the disease, my friend did not seek the help of a professional doctor. He could have easily obtained anti-retroviral drugs to treat his symptoms but he instead chose to use products promoted by faith healers, believing they could cure him. They couldn’t, and by the time he was admitted to hospital, his days were numbered.

I wanted to find out more about the product advertised on the bus so I called the number on the ad. I said I had a friend who had contracted HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, and the woman who answered the phone asked me to make an appointment.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

When I arrived at her flat, near the University of Dental Medicine in Thingangyun Township, she showed me a bottle of Thai traditional medicine. A bottle of 60 capsules cost K100,000 and the medicine needed to be taken for about a year, she said.

In spite of the products she was peddling, in my mind I had some admiration for her because she answered my questions with respect and patience, something that rarely happens at clinics and hospitals in Myanmar.

My mother died of liver cancer last summer. She had been diagnosed with the disease about two years earlier. I was with her when she was being treated, which gave me an understanding of patient-doctor relationships in Myanmar.

No doctor ever explained my mother’s situation and treatment as patiently as the woman who was selling this Thai medicine. My mother often spent less than five minutes in the consulting room when seeing doctors, an issue that is common in Myanmar.

I took a train home from my appointment with the woman selling the Thai traditional medicine and, by coincidence, there was a man in my carriage selling a product he said could cure cancer.

His medicine was large seeds that he sold in glass bottles for K250. He said women with breast cancer could treat it by grinding the seed in water and applying it to their bodies. He said the seeds were called budalet and could cure ailments of the skin, eyes, urinary tract and teeth, as well as cancer.

I bought K1,000 worth of seeds because I wanted to take a closer look. About 15 other people bought seeds, too. As they were being sold another vendor appeared, with a powder that she said could cure toothache.

None of these medicines have been registered. There has been no research to determine if they are really effective. Selling these products is illegal. The maximum penalty for selling fake or unregistered medicine is seven years’ imprisonment and a fine of K500,000.

Since 2014, the Myanmar Food and Drug Administration detected about 63 kinds of fake or unregistered medicine on the market, mainly originating from Thailand, China and India.

Dr Theingi Zin, director of FDA, said legal action had been taken in 80 cases involving fake or unregistered medicine.

Despite the risk of a jail sentence, there is a thriving market in Myanmar for fake and unregistered medicine and products sold by faith-healers. Most buyers of these products have cancer or other diseases that are hard to treat or cure.

Targeting the poor

The mother of a friend needed radiotherapy to treat her cancer every month. There was a long wait for treatment in Yangon so she used to travel once a month to Mandalay to be treated there. She had to make the journey because she could not afford to be treated at a private hospital in Yangon.

Being diagnosed with cancer in Myanmar can feel like a death sentence, especially for those of limited means. It is no coincidence that the targets of faith healers and those selling fake medicine are patients at the grass roots.

There was a noticeable increase in faith healers and the sale of fake medicine after 2010, said U Aung Naing, a consumer rights activist.

“They approach patients directly, going door-to-door, and it is difficult for the authorities to detect them,” said Aung Naing, who has held positions with the Myanmar Consumer Protection Association and the Myanmar Consumers Union.

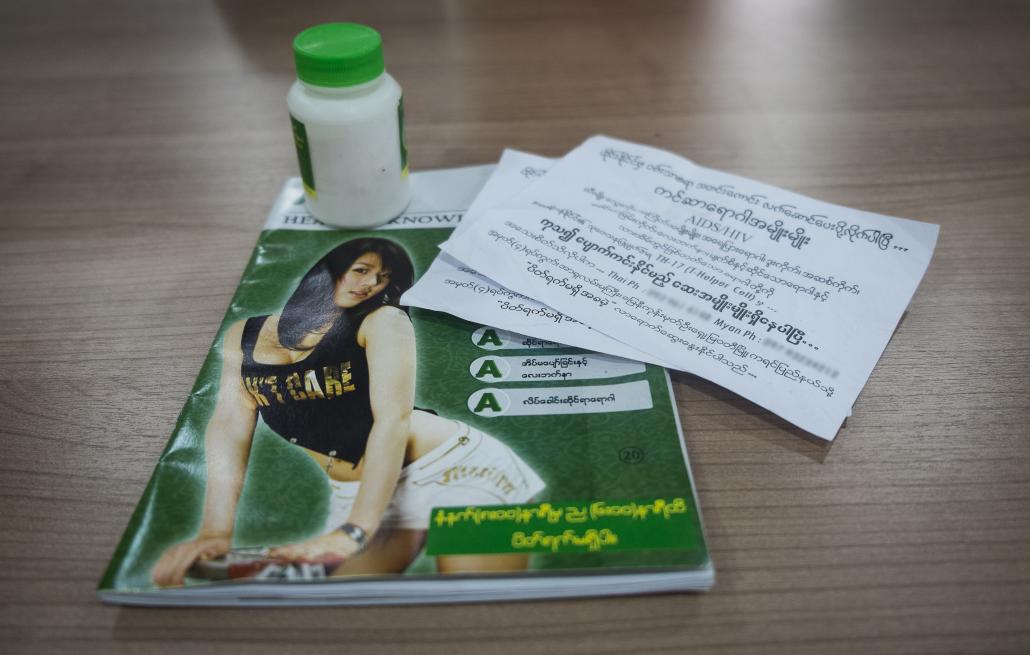

A magazine and pamphlet advertising an unregistered drug that claims to cure HIV/AIDS. (Teza Hlaing / Frontier)

Patients who rely on faith healers or fake medicine to treat HIV/AIDS are unlikely to speak out if they are cheated because of the stigma attached to the disease.

Concern has been raised about the aggressive advertising and high fees of some clinics that claim to be able to treat cancer.

I paid a visit to one of these clinics in Bo Myat Tun Street in downtown Yangon. It calls itself the Asia clinic but used to be named the New Hong Kong clinic. I was told the cost of treating a cancer patient with Chinese traditional medicine would be at least K250,000.

In 2014, the government issued warnings to eight Chinese clinics over aggressive advertising and unlicensed doctors.

Dr Pe Thet Khin, the health minister in the previous government, said it was difficult to take action against the Chinese clinics because they used neither Western medicine nor Myanmar indigenous medicine.

Dr David Kyaw, a retired professor of forensic medicine, was highly critical of the exaggerated claims made by some clinics.

“They are advertising that they can treat any disease, big or small, in one stroke,” he was quoted as saying by 7Day Daily. “If action is taken against one, another 10 will get away and start a clinic in another place with another name.”

If you are diagnosed with a disease in Myanmar you have three choices for treatment. If you have enough money you can be treated in a private hospital. Otherwise you can wait in line at a government hospital or put your trust in a faith healer.

Top photo: Ann Wang / Frontier