The November 8 election will be a tough test of the commitment to democracy and human rights of controversial social media giant Facebook, and there are several steps it could take to preserve the integrity of the vote.

By EVA GIL and RAFAEL GOLDZWEIG | FRONTIER

All eyes will be on the November US presidential election to judge whether Facebook is doing enough to prevent online disinformation and foreign influence. But November will bring another election that will test the company’s commitments to democracy and human rights. Myanmar is a primary example of how tech companies can fail citizens if they do not act strongly against online hate in conflict-ridden countries.

In its 2018 report, the Independent International Fact Finding Mission on Myanmar stated that “Facebook has been a useful instrument for those seeking to spread hate” against the Rohingya. The report recognised that Facebook had tried to respond to misuses of its platform, but found it “slow and ineffective”. Myanmar’s November 8 general elections are thus a new test on the company’s efforts.

A closer look at what messages are going viral on Facebook, where they originate and how they travel can give us important hints about whether the company has invested enough to tackle some of the shortcomings that were evident prior to 2017. The election in Myanmar will be a sensitive moment in which hate speech and disinformation could resurface. In recent months, Facebook has initiated a dialogue with election stakeholders in Myanmar, investing heavily to prevent abuses in a country where the company has taken a reputational hit for unwittingly contributing to conflict and violence.

To test such commitments, Democracy Reporting International monitored the political debate online in Myanmar, analysing over 33,000 posts from Facebook pages and groups that were uploaded between November 2019 and January 2020. The data shows how nationalism and national security topics have taken a prominent role in Myanmar’s online discourse ahead of elections. As November 8 nears, polarising rhetoric on the platform will most likely increase.

Some of these pages were taken down by Facebook in April 2020, but many of them still exist. Ahead of the election, Facebook could provide more clarity on its criteria for taking down pages and contribute to further transparency by publishing a Myanmar-specific monthly report on its actions during the election campaign. Content taken down during elections should be available in an online archive for further evaluation.

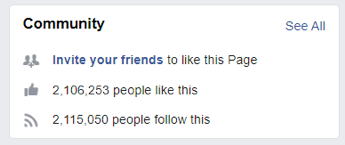

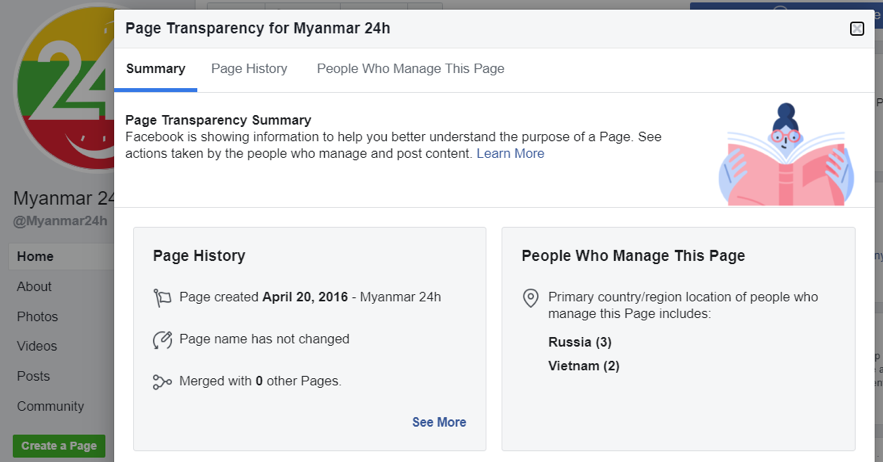

Even more problematic are pages with unclear affiliations operated from outside the country that are publishing or sharing news about politics and national security. Our research found that the “Myanmar 24h” page, which has over two million followers, shares news content in Burmese, but is operated from Russia and Vietnam.

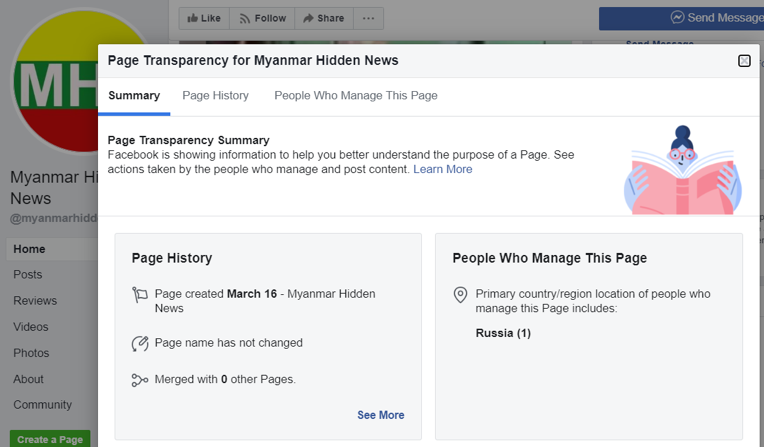

News published by this page is mostly critical of the government or the National League for Democracy headed by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, and often re-shares content from another page, “Myanmar Hidden News”, which is also operated from Russia. This re-sharing of content boosted the audience of the page, which was created in March, from zero to 11,000 followers in only two days, highlighting a strategy of creating different false news portals to share misleading content at scale. These kinds of pages can create serious damage during elections, including spreading misinformation or contributing to polarisation.

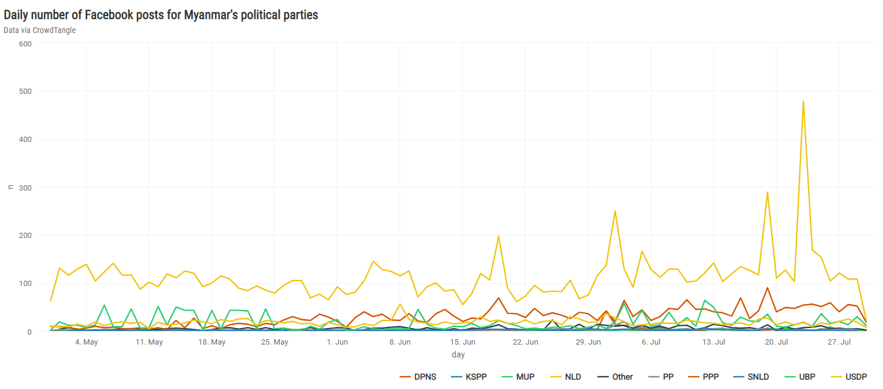

Online campaigning will play an important role in the election because COVID-19 prevention measures are likely to restrict candidates’ access to voters. DRI’s research found that the governing NLD has already developed a solid network of Facebook pages, achieving high reader engagement by sharing similar content systematically across different parts of the county. So far, no other political party has a comparable social media reach.

But official party and candidate Facebook pages are only part of the story. In our experience, parties may create other thematic Facebook pages to share content, including misinformation and defamation, to obtain political support for their candidates. This is also likely to happen in Myanmar. Together with the network of junk pages, we expect to see online space poisoned by false information and possibly hate speech.

Facebook has tried to increase transparency in political advertising in Myanmar, by opening an Ad Library and establishing ad enforcement procedures in recent months. It will be important to adapt the standards for political advertisement to local regulations, including allowing political ads only during the campaign period and respecting silence periods. Also, Facebook could provide features such as the Ad Library report, which it makes available mostly to European countries and a handful of others and that discloses aggregated data on funds spend on advertisements.

US democracy may again be damaged by manipulative interference in its coming election, but in a fragile democracy such as Myanmar such activities can be fatal to nascent democratic institutions and can contribute to fostering violence again. Although Facebook has increased spending to prevent online manipulation in Myanmar in recent years, we can still see all the enabling elements of a successful electoral manipulation campaign: the coordinated sharing of junk domains, shady pages operated from abroad influencing the political debate, regulation of political ads ignored and a low reach of voices from an incipient civil society. In addition, low digital literacy could be abused to suppress voter turnout or confuse voters.

A key step towards preserving electoral integrity in Myanmar would be for Facebook to provide further transparency on advertisements placed as well as its content moderation efforts, allowing stakeholders to understand how it deals with election-related (mis)information on the platform through monthly reports, and how this has affected the election campaign.

It is not too late to ensure the integrity of online discourse but Facebook must step up its efforts now.

Eva Gil and Rafael Goldzweig are country representative for Myanmar and research coordinator, respectively, at Democracy Reporting International, which works on social media monitoring in Myanmar with the support of Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (giz). DRI will focus on social media and Myanmar’s general election as part of the EU-funded STEP Democracy Programme and is grateful for Facebook’s support in providing access to data through the CrowdTangle platform.