Voters and politicians in Yangon and Kachin State say inadequate voter education and bureaucratic ineptitude meant some ethnic minority voters were denied ballots to elect ethnic affairs ministers.

By YE MON | FRONTIER and ESTHER | MYITKYINA NEWS JOURNAL

Leading up to and on election day, the Rakhine ethnic affairs minister-elect for Yangon Region, Daw Htoot May, received “hundreds” of phone calls from aggrieved Rakhine people in Yangon. They told her they were unable to vote for their ethnic affairs minister because they were not on the relevant voter list, though like other voters they were able to cast ballots for their regional and Union MPs.

The complaints came as the Rakhine residents of the commercial capital voted on November 8 and in the week before election day. This advance voting option was provided to people aged over 60, to protect this vulnerable group from catching COVID-19 in crowded polling stations.

The Rakhine minister-elect – who ran as an independent because the Arakan National Party refused to let her to resign so she could stand for a rival Rakhine party, the Arakan League for Democracy – told Frontier on November 15 that she had submitted several letters asking the Yangon election sub-commission to rectify the problem between November 5 and 8, but got no response.

“It was shameful of the election commission,” she said.

Rakhine voters in Yangon were not the only ones to experience this form of disenfranchisement. Many Karen in the city reported arriving at polling stations and finding they were not registered to cast an extra ballot for Yangon Region’s Karen ethnic affairs minister.

Naw Ohn Hla, who vied for the Karen ethnic minister position with the United Nationalities Democratic Party, told Frontier on November 16 that she had also heard of many Karen people in the city who faced the same problem. Ohn Hla, who lost out to Naw Susanna Hla Hla Soe of the National League for Democracy, said she is discussing with party leaders whether or not to submit an official complaint to the Union Election Commission.

‘The commission should have explained’

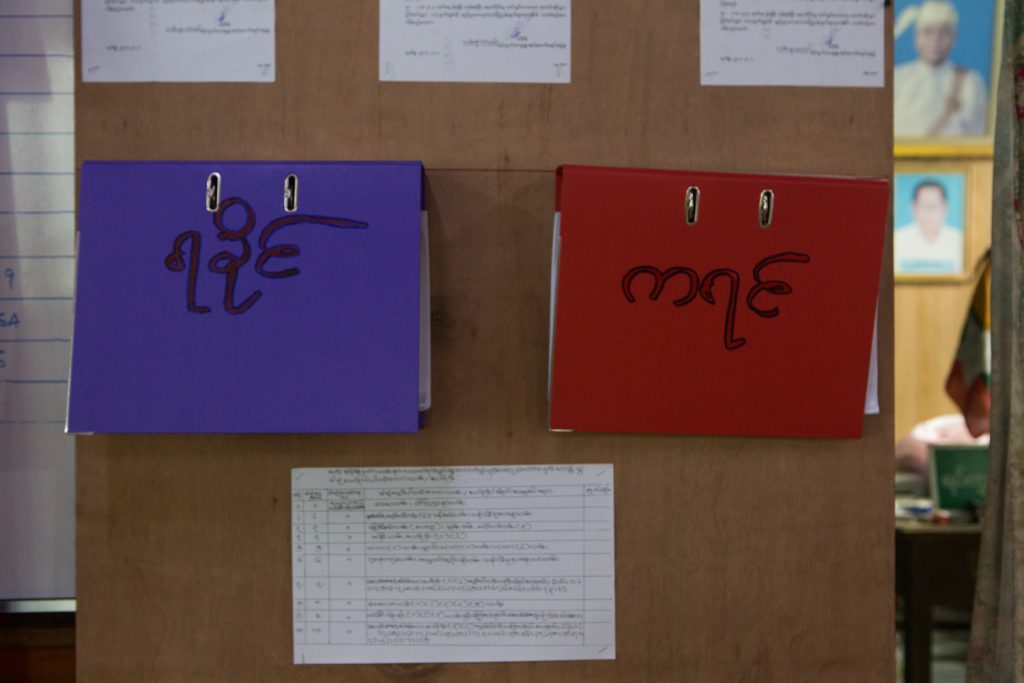

The main problem seemed to be that many of these voters were unaware that there is more than one voter list. In addition to the general voter list, which enables them to cast ballots to elect Amyotha Hluttaw, Pyithu Hluttaw and regional hluttaw MPs, there’s a separate list of Rakhine voters eligible to vote for candidates vying to be Yangon’s Rakhine ethnic minister, and a list of Karen voters who elect the Karen ethnic minister.

As with the general voter list, these ethnic voter lists are compiled by local election sub-commissions using official household and population data, complemented with door-to-door checks, without voters having to actively register. All the voter lists were publicly displayed ahead of the election – for one period in late July and early August, and another in early October – and voters were expected to check their accuracy. If they found themselves missing, either from the general or an ethnic voter list, they could apply at their ward or village tract sub-commission to be added.

However, many ethnic voters said they had not been told they needed to check two different voter lists, suggesting not enough voter education had been done. This was a problem particularly because the lists had been redrawn from the last election in 2015. Some voters claimed they had cast a ballot for their ethnic minister in previous elections but discovered too late that they were missing from the ethnic voter list for this year’s vote.

Ko Kyaw Ye Lynn, 38, a voter in Yangon’s Hlaing Tharyar Township, was among them. He had believed that being marked as ethnic Karen on his Citizenship Scrutiny Card was enough for him to be issued a ballot to elect the Karen ethnic minister. He had not checked the Karen voter list prior to voting for the position in 2010 and 2015, and he was not aware of the need to do so this year.

“If ethnic people need to check two lists, the [election] commission should have explained that to people, but they didn’t,” he told Frontier.

When Kyaw Ye Lynn found on November 8 that he was not registered as a Karen voter, the head of his local polling station told him to contact the ward administrator, suggesting that a last-minute inclusion in the ethnic voter list might have been possible. However, Kyaw Ye Lynn said he was too busy that day to pursue the issue further.

During advance voting for elderly citizens, bureaucratic breakdown rather than incorrect voter lists was seemingly to blame for some ethnic voters being denied their extra ballot. The hastily arranged measure was prompted by Myanmar’s “second wave” of COVID-19 infections, and in Yangon Region alone about 800,000 were eligible, of whom more than 600,000 voted. The scale of the process and the limited preparation time led to scores of complaints in Yangon and elsewhere in Myanmar of electoral procedures being violated.

Daw Htoo Htoo, a 60-year-old resident of Yangon’s Sanchaung Township and an ethnic Karen, told Frontier on November 15 she was unable to vote for the Karen ethnic minister because she did not receive the relevant ballot paper from her ward election sub-commission while voting in advance on November 3. She was able to vote for her other representatives.

“I have voted for the Karen ethnic affairs minister since the 2010 election, but I couldn’t this time,” said Htoo Htoo.

However, this did not appear to be because she was not registered to vote for the Karen ethnic minister. Her daughter, who voted on election day, said she saw Htoo Htoo’s name on the Karen voter list displayed at their local polling station.

Htoo Htoo said the officials overseeing advance voting told her to go to the polling station on election day if she still wanted to vote for the Karen ethnic minister, but she thought it was not worth the risk of catching the coronavirus and gave up on that vote. She added that she had also not been told of the need to check a separate voter list ahead of the election – though in her case, inclusion in the Karen voter list did not seem to be the problem.

Beyond Yangon

Apparent failures in voter outreach also prevented ethnic voters from taking advantage of a reform to make the election of ethnic ministers more inclusive. This caused some consternation in Kachin State, whose state government includes four ethnic affairs ministers, for the Bamar, Shan, Lisu and Rawang communities in Kachin.

In 2015, voters of mixed ethnicity could only vote for the ethnic affairs minister representing the group their father belongs to, according to U Tun Aung Khaing, deputy director of the Kachin State election sub-commission. But this year, he said, people of mixed heritage were given the right to choose which ethnic minister they wanted to vote for.

However, as a default, ethnic voters were still registered by officials on the voter list corresponding to their father’s ethnicity. If they wanted their names to be switched to another ethnic voter list that matches their mother’s heritage, they had to apply to do so during the voter list display period ending on October 14.

After that date, it was too late to switch, said U Than Swe, chairman of the township election sub-commission in the state capital, Myitkyina. “They can’t change it now,” he said on November 1, a week ahead of the election. “If they are on the Bamar voter list, they vote for the Bamar ethnic affairs minister, and if they are on the Shan voter list, they have to vote for the Shan ethnic affairs minister.”

But, echoing their counterparts in Yangon, ethnic voters and politicians in Kachin say the opportunity to choose was not properly communicated to the public.

“Many people don’t know about the change,” Sai Kyaw Htwe, chair of the Tai-Leng [Red Shan] Nationalities Development Party, said on November 2. He said that when election officials went door to door to prepare the voter lists, they did not explain to voters that they could choose the ethnic affairs minister they wanted to vote for.

“When the voter list was compiled, no one asked whether mixed Shan-Bamar people wanted to vote for the Shan ethnic affairs minister or the Bamar ethnic affairs minister,” he said. “People should have been informed in advance that voters holding Shan-Bamar citizenship IDs could choose.”

‘It should never happen again’

Myanmar’s 14 state and regional governments include 29 ethnic affairs ministers, who are directly elected by voters from the relevant ethnic group. The 2008 Constitution says that any ethnic group that has at least 0.1 percent of the national population – just over 50,000 people – within a given state or region in which it is not a majority gets an ethnic affairs minister. However, minorities with their own self-administered zones, such as the Pa-O, Danu or Naga, are ineligible for an ethnic affairs minister in the state or region where the zone is located. No new ethnic affairs minister positions have been created since the current 29 were devised in 2010, despite the 2014 census revealing the prevailing nationwide population estimate of 60 million to be eight million too high.

The constitution does not define the position’s scope. While the 2015 Ethnic Rights Protection Law charges ethnic affairs ministers with protecting and scrutinising violations of “ethnic rights”, these are also not defined in this or any other law. This vague mandate, together with section 10(b) of the 2010 Region or State Government Law – which states that they can be assigned to other duties by the chief ministers of states and regions – has meant that ethnic affairs ministers have often been assigned to portfolios with little relation to ethnic affairs. For instance, in Yangon, outgoing Rakhine ethnic minister U Zaw Aye Maung of the ANP has handled labour relations, while the outgoing Karen ethnic minister, Naw Pan Thinzar Myo of the NLD, has overseen tourism and been the regional government spokesperson. Both chose not to recontest their seats this year.

Twenty-three of the ethnic minister posts were won on November 8 by NLD candidates, and one each by the Mon Unity Party, Lahu National Development Party, Lisu National Development Party and Kayan National Party. Besides the Rakhine ethnic minister-elect in Yangon, Htoot May, one more independent candidate, Zuk Dau, was elected, in his case to be the Kachin ethnic minister in Shan State.

In Yangon, almost 150,000 people voted for the Karen ethnic affairs minister, of the more than 235,000 who were eligible to, while for the Rakhine ethnic affairs minister, almost 45,000 of the more than 73,000 eligible voters cast ballots.

In Kachin, 147,150 of the 210,968 people registered to vote for the Shan ethnic affairs minister cast their ballots.

Htoot May in Yangon refused to say whether she thought the election was free and fair. However, she insisted that so many ethnic voters being unable to vote for their ethnic affairs minister was a blemish on the UEC.

“The commission should take care of this for future elections,” she said. “It should never happen again to ethnic people.”