The decision to issue ‘notices to proceed’ to four consortia for LNG and natural gas power projects is a decisive move but some argue the government is taking on too much risk.

By THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

JANUARY 30 was the biggest day for Myanmar’s power sector in many years. At a ceremony in Nay Pyi Taw, the government green-lighted four private sector projects that, if implemented, would double the country’s generation capacity over the next four years.

Since taking office in March 2016, the National League for Democracy government has been accused of dragging its feet on the country’s power problem. But U Win Khaing’s ascension as minister for electricity and energy and the realisation that the next election is less than three years away appears to have focused minds in the government and NLD.

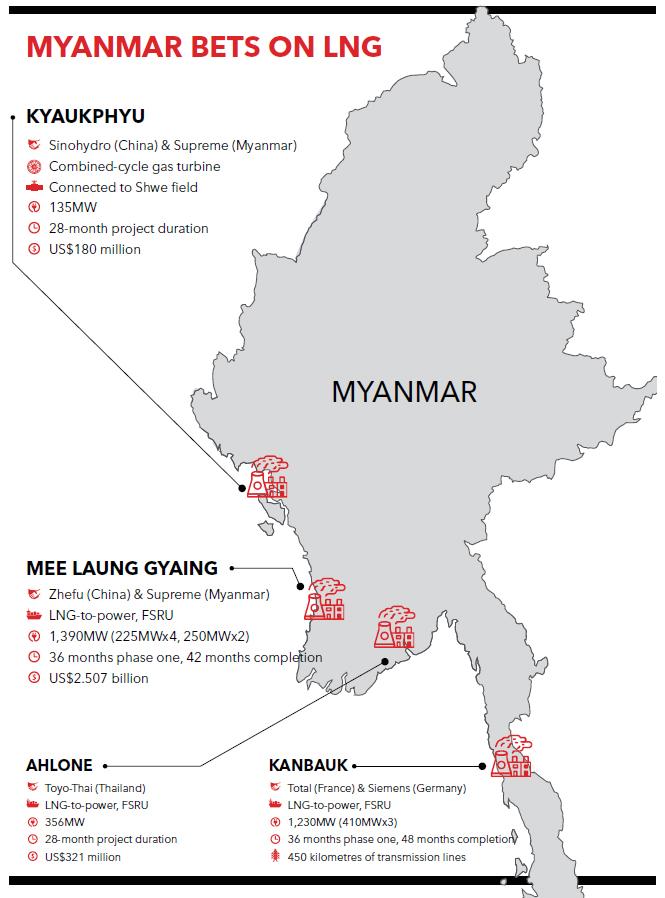

The government hopes to have at least some of the proposed plants operational by the middle of 2020, giving two developers a 28-month deadline. Three of the projects, at Kanbauk in Tanintharyi Region, Mee Laung Gyaing in Ayeyarwady Region and Ahlone in Yangon Region, are for imported liquefied natural gas. A fourth, at Kyaukphyu in Rakhine State, is for natural gas from the Shwe field.

While the announcement was a surprise, the decision to pursue an LNG solution was not. In reality, the government had few other options. There’s simply not enough domestically produced natural gas to go around, and no new fields are likely to come online within five to seven years. Hydro and coal are unpopular; dams can take up to a decade to build, even when the process is smooth.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“The government’s making extra steps to boost exploration and production but in the timeframe that they need electricity they need a quicker solution,” said Mr Marc Howson, director for LNG market development at S&P Global Platts. “It really leaves LNG as the most viable option.”

In September 2016, the ministry sought expressions of interest for LNG projects. It received more than 100 proposals; a tender or request for proposals was expected, but never called. The four projects issued with a “notice to proceed” last week were the result of direct negotiations rather than competitive bidding.

In a long interview with state media on January 30, Win Khaing outlined the ministry’s bold plan to meet the country’s rapidly growing power needs.

“The power supply is the first question asked by foreign and local investors. Today, we can say that we can take responsibility for a reliable power supply by 2020,” he was quoted as saying. (The ministry did not respond to requests for comment following the announcement.)

The big bet on LNG has its detractors, though. One industry source described the announcement as a “disaster”, telling Frontier that the cost to the ministry of buying power from the plants could “bankrupt” the sector.

Even those who are more positive about the announcement are cautious about the chances of the consortia meeting the ministry’s very ambitious completion dates.

Mr Eric Shumway, associate director at Delphos International, a project financing advisory with experience in Myanmar and across the region, said there were some “very positive” aspects to the announcement – not least that it was “a concrete sign of action from [the ministry] after a couple of years of silence”.

But he said the Kanbauk and Mee Laung Gyaing projects were “very complicated undertakings”, and completion of the first phase would likely take at least four years rather than the three that the ministry has said. “The two large projects will require highly experienced developers.”

Shumway said the biggest risk to the government’s approach relates to the nature of the “notice to proceed”.

“It is not clear what this means in the absence of any deal documentation,” he said, adding that many of the projects appeared to be at a relatively early development stage. “I worry that [the ministry’s] rush to get a PR ‘win’ with this announcement of over 3,000 MW of capacity might close off discussions on other promising power projects … on the grounds that [the ministry’s project] pipeline is already full.”

The projects

At Kanbauk, French company Total and Germany’s Siemens will install 1,230MW of capacity in 48 months. The 615MW first phase will come online in three years.

Frontier understands that the project will redeploy some infrastructure from the Yadanar offshore field, which is operated by Total. Output from the field has plateaued and is expected to decline from 2021. Most of the gas is sold to Thailand through a pipeline that makes landfall at Kanbauk. Total declined to comment further on the project by deadline.

A ministry official said the Total/Siemens consortium would also build hundreds of kilometres of high-voltage transmission lines to connect the plant to existing high-voltage lines at Payagyi in Bago Region.

The official said the investment in infrastructure would likely be borne by the investors and recouped through power sales to the government.

“Myanmar can’t yet produce LNG on its own as it requires a huge investment and technology,” said the director, who was not authorised to speak to the media. “The agreement is likely to state that all of the investment will be covered by the consortium.”

A map of Myanmar’s LNG and natural gas power projects. (Frontier)

At Mee Laung Gyaing, China’s Zhefu and local company Supreme Group will undertake a 1,390MW LNG project, with the first phase to be completed in 36 months and full capacity ready in 42 months.

As Frontier reported on January 25, the Mee Laung Gyaing project is on a remote stretch of coast north of Chaungtha in Pathein Township. The company plans to build a floating storage regasification unit about 1.6km offshore where 80,000-tonne tankers will be able to dock and offload LNG for the plant.

Supreme Group executive director U Htu Htu Aung told Frontier that the “notice to proceed” was a “firm approval” from the government that would enable to developers to move on to implementation.

“The next steps will be to negotiate and sign project agreements with the Ministry of Electricity and Energy, complete the EIA, SIA, [achieve] financial closing, and construct the power plant, transmission lines and related facilities,” he said, adding that the target timeframe for completion was “quite realistic”.

The other two projects are much smaller and will both be implemented in 28 months, the ministry said.

At Ahlone, Thai company TTCL – better known as Toyo-Thai – will build a 356MW LNG-to-power plant, while at Kyaukphyu China’s Sinohydro and Supreme will implement a 135MW combined-cycle gas turbine project. Kyaukphyu will almost certainly be the most straightforward of the four, as it is domestic gas rather than imported LNG, and most of the necessary supporting infrastructure is already in place.

Done and dusted? Not quite…

It’s not clear what the “notice to proceed” really means in a practical sense, except that these projects have the government’s imprimatur. While it’s a signal to other consortia not to bother proposing any new projects, it’s not a guarantee these particular projects will ever come to fruition.

The four consortia have much left to do. One of the most important documents for an independent power project (IPP) is the power purchase agreement (PPA), which states the price at which the government will buy power from the producer. None of the consortia appear to have a PPA in place.

Once the PPA is signed, they will then need to use it to attract billions of dollars in financing. Assuming the PPAs are properly negotiated, this could take up to a year, sources in the industry say. The issue of sovereign guarantee – a legal guarantee from the government that it will buy power for the term of the PPA at the specified rate – has held back private investment in the sector, and has not been publicly discussed in relation to the four projects. Under the Public Debt Management Law, a formal sovereign guarantee would require the government to seek parliamentary approval but this has not yet been tested.

With the possible exception of ToyoThai, they will also have to navigate land use issues, particularly for transmission lines. Kanbauk will require hundreds of kilometres of high-voltage power lines to connect it to Mawlamyine in Mon State or Payagyi in Bago Region, while Mee Laung Gyaing will have to overcome a similar issue. The ToyoThai project will face its own distinct challenges, particularly how to get LNG tankers through the shallow and congested Yangon River.

Kyaukphyu and Ahlone will benefit, however, from already having the land and most of the infrastructure in place.

In the state media interview, Win Khaing said discussions were already well underway on these issues with the investors. “We talked about delivery and power purchase agreement with the companies which are willing to make investment in our country,” he was quoted as saying. “We discussed transmission lines and power supply in line with the policies of our country and had chosen four LNG plants.”

A ‘slippery slope’

One critic of the government’s plan is the World Bank. Mr Sunil Kumar Khosla, the bank’s lead energy specialist, said it had been advocating for a “two-step approach” that would include a planning exercise to identify the best power generation options and then conduct a tender to ensure the government receives the best price.

“It seems both these steps were not followed while deciding these projects. We intend to do analysis to evaluate the relative merits of these project for the Myanmar system in the next few weeks,” Khosla said in an email.

In 2016, the World Bank commissioned consultants to examine Myanmar’s LNG options, including five potential sites for a floating storage regasification unit – a portable dock where LNG is unloaded and decompressed. However, none of these were “integrated solutions”, where the FSRU is linked to a power plant and the power generated transmitted to the grid. Instead, the decompressed gas would have been piped to plants around the country, with a focus on Yangon because of its high demand.

Frontier understands that based on the results of the consultancy the World Bank has advised the government against an FSRU and instead been advocating for a more modest project that would enable small tankers to deliver LNG directly to a site in Yangon. The ministry could then have conducted tenders to upgrade existing plants around Yangon, improving their efficiency three or four-fold.

An LNG tanker is towed along the Straits of Johor between Malaysia and Singapore. (AFP)

Another industry source said the government was “playing with fire” by choosing such large projects with their own FSRU. For such LNG-to-power projects to be economic, they need to be operating at full capacity virtually all the time – regardless of whether the power is needed.

“You’re going to be paying not just for the capital cost of the power plant but also the FSRU, and then you’re going to be paying for the energy charges [of imported LNG],” he said.

“In this case, irrespective of whether you need 1000MW despatched, you have to pay for 1000MW … For 20 or 30 years, Myanmar will have to continue paying them. This is a very slippery slope.”

Having its own FSRU or onshore facility would have given the government to control over LNG supply to privately run gas-fired plants. That means it could have reduced output when production from hydro dams is high, or if more domestically produced natural gas comes online.

“Independent generation is not necessarily bad but you need to be cognisant of whether your demand will grow.”

“The big problem here is they have not done any planning around where they want to put the plants and what capacity they want the plants, and they haven’t done any comparative bidding. These consortiums have been selected on a random basis.”

‘Myanmar urgently needs new power plants’

But Shumway from Delphos said the risk of having to pay for excess power was better than not having enough.

“Sure, LNG-to-power projects are more risky than ordinary gas-fired projects on several scores,” he said. “Then again … what are the options? Myanmar urgently needs new power plants of all types.”

He also objected to the “development bank dogma” that every project should go to competitive tender, pointing out that two of the four approved projects – Kanbauk and Ahlone – are brownfield sites that rely on infrastructure already controlled by the developer.

“How does one compel a private party to offer these features to other bidders? … If these project features truly add value and bilateral negotiation is not possible, that value is lost,” he said.

“Although competitive procurement is generally the preferred way to go and can yield good outcomes – such as we saw in the International Finance Corporation-led Myingyan procurement process – the reality is that competitive procurement can take significantly longer than bilateral negotiations. Bilateral deals should never have been closed off as an option so early in the development of this market.”

Howson from Platts said that if the three projects in Myanmar were all completed as planned they would have a “fairly significant” impact on regional LNG demand. Although ASEAN is a net exporter of LNG, supply – mostly from Indonesia and Malaysia – is relatively stable at 50 million tonnes per annum while demand is rising rapidly from countries like the Philippines and Thailand.

“You’re talking a couple of million tonnes per annum of LNG demand in a region that currently has a demand total of 11 million tonnes,” he said.

He added that Myanmar was entering the LNG market at a time of rapid change. Global production is forecast to rise 50 percent from 2015 to 2020, while many buyers are increasingly choosing shorter-term contract and spot prices over long-term contracts, which were traditionally pegged to oil prices. This change is because of the increased confidence in the security of supply offered by the LNG spot market and uncertainties over demand.

“For a new importer like Myanmar it represents a nice opportunity,” Howson said. “If you buy on the spot markets you can very quickly curtail LNG imports if and when domestic gas production eventually ramps up.”

TOP PHOTO: AFP