Distilleries are coming under increasing pressure from the government and the public to install systems to treat the huge volumes of wastewater they discharge into the environment.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

Photos TEZA HLAING

U BA KYI, a farmer in Ashay Thae Phyu village in western Yangon Region’s Htantabin Township, woke early and went to a nearby canal. He removed plastic bags filled with rice seeds and laid out the seeds to dry in the sun. His clothes reeked from the stench of the canal water.

Normally, after a few days the seeds would germinate and be ready for planting. But not this time – all of the seeds were rotten. It was 2013. Ba Kyi was not alone; scores of other paddy farmers in Ashay Thae Phyu, a village of 200 households, were having the same disappointing experience. The canal water was killing their rice seeds. They had to buy seeds to grow paddy that year. For Ba Kyi that meant the unexpected cost burden of having to buy enough seeds to plant on his 27 acres of paddy fields.

The farmers had also used the canals near the village to raise fish and prawns for consumption. But after a liquor factory owned by Hteik Shwe Yee Oo Co was established near the head of the canals in 2013, the catch of fish and prawns had declined.

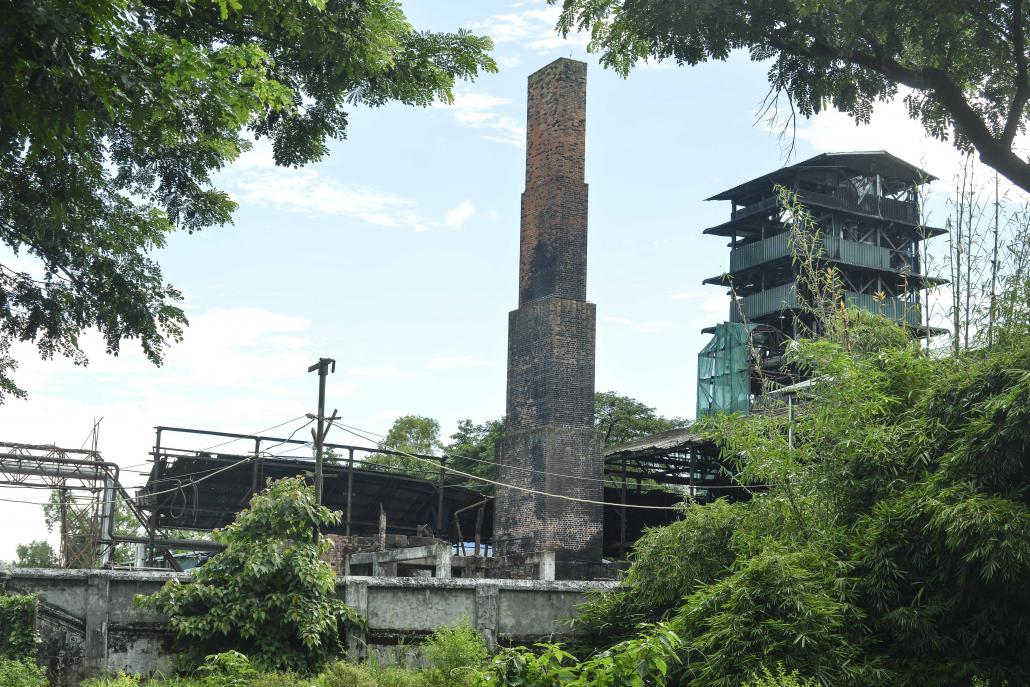

Yangon distillery in Thaketa Township is one of more than 40 distilleries across the country. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The residents of Ashay Thae Phyu are among hundreds of thousands of people in townships throughout the country whose lives have been affected by untreated wastewater from distilleries, say MPs and environmental groups.

In its first year in office, the National League for Democracy government began paying attention to complaints about wastewater pollution from distilleries, which are licensed by the Ministry of Home Affairs. The issue had been largely ignored under previous governments.

“As the responsible departments lacked the resources to address the problem, the factories discarded wastewater without properly treating it,” said Pyithu Hluttaw MP U Khin Maung Latt (NLD, Myanaung, Ayeyarwady Region).

New rules of the game

The 2012 Environmental Conservation Law and related provisions in bylaws enacted in 2014 stipulate that wastewater from factories must have a COD of less than 225 parts per million, a BOD under 50ppm and a pH level between six and eight.

Last month, the Ministry of Home Affairs issued notices warning distilleries across the country that they have six months to install wastewater treatment plants. Once the plant is installed, an inspection team will check that the wastewater meets the required standards. Only if it does will they be permitted to continue operations.

Just a handful of distilleries have wastewater treatment systems in place, but the government has set a six-month deadline for them to clean up their act. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

In response, the Yaung Ni distillery in Myanaung has begun a six-month trial of a biological wastewater treatment system that was recently installed at a cost of US$2 million (about K2.7 billion).

“This system is simple,” said U Kyaw Thein Lwin from Kyar Min Gyi, the company that owns the factory.

The wastewater, he said, is treated to reduce the COD (chemical oxygen demand) and BOD (bio oxygen demand) rates. “Then we could dispose of the wastewater anywhere,” he said.

However, many distilleries are reluctant to install the expensive wastewater treatment systems and take responsibility for the pollution they are causing. Kyar Min Gyi, for example, has yet to install a wastewater system at its distillery at Samalauk in Nyaungdon Township due to the high cost, Kyaw Thein Lwin said.

“There are more than 40 distilleries throughout the country producing overproof alcohol, but only a few have begun installing this biological treatment system,” said U Nay Win, secretary of Green Images Myanmar, an environmental group focusing on wastewater management.

Just a handful of distilleries have wastewater treatment systems in place, but the government has set a six-month deadline for them to clean up their act. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

He said the government needs to closely monitor distilleries to ensure they are complying with anti-pollution guidelines. He said he was worried that the government lacked the will or ability to enforce the standards.

A few months ago, the Yangon Region government ordered Hteik Shwe Yee Oo, the operator of the Khabaung Shwe Yee distillery near Ashay Thae Phyu, to cease operations. The distillery in Kyat Khanar village has been dumping untreated wastewater into canals that eventually empty into the Hlaing River.

However, during a recent visit with Green Images Myanmar and two community leaders from Ashay Thae Phyu, the distillery appeared to be operating in defiance of the ban.

Htantabin township administrator U Than Zaw Lin said some of the distilleries in the area had been given a 15-day extension so they could use up all their remaining raw materials rather than let them go to waste.

The Ayeyarwady Region government ordered the Kyar Min Gyi distillery in Samalauk village tract, Nyaungdon Township, to close until a wastewater treatment system has been installed. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

The General Administration Department under the military-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs is the main body authorised to issue licences for alcohol-related businesses, ranging from liquor shops to distilleries and breweries. Final decisions rest with the GAD, although it considers recommendations from the Environmental Department of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation and the Directorate of Industrial Supervision and Inspection under the Ministry of Industry.

In mid-August, the GAD ordered five distilleries in the Shwe Pyi Thar industrial zone on Yangon’s northern outskirts to suspend operations because none of them had installed a biological wastewater treatment system. Several sources confirmed that the distilleries are complying with the order.

“As the perfect treatment system might involve an investment of $2 million, businessmen might shrink from the cost. But if they install a sustainable system, the pollution risk to public health will decline,” said U Kyaw San Naing, a director of the Environmental Conservation Department.

Win Brothers Holding Myanmar is one of the few private businesses to have installed biological treatment systems in its distilleries; the Shwe Min Pyan plant established in Mandalay in 1992 and the Yangon Distillery factory in Yangon’s outer eastern Thaketa Township, established in 2004.

The Ayeyarwady Region government ordered the Kyar Min Gyi distillery in Samalauk village tract, Nyaungdon Township, to close until a wastewater treatment system has been installed. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

Win Brothers makes a well-known tipple, High Class whisky. Its two distilleries also sell overproof alcohol to the companies that make Royal Club and other domestic whisky brands.

U Thein Lin, a chemical engineer and production director at Win Brother, said other distillery companies needed to take responsibility and treat wastewater.

“We cannot get any profit back from wastewater treatment, but as we are earning money from this business we should take responsibility for factory emissions,” Thein Lin told Frontier.

Disposing of untreated wastewater could damage all land and water resources, including underground water, and the ecosystem. It can also cause health problems, he said.

‘We’ve got our fish back’

Residents of Samalauk village tract, in Ayeyarwady’s Nyaungdown Township, about 32 kilometres (20 miles) west of Htantabin, say pollution from the nearby Kyar Min Kyi distillery has made their lives a misery since it went into operation in 2009.

The distillery, in the middle of the village tract near a monastery, primary school, hospital and police station, produces thousands of litres (gallons) of overproof alcohol a day. Residents say the smell, noise and environmental pollution it causes has badly affected the quality of their lives.

Ko Arkar Phyo, a fisherman born and raised in Samalauk, told Frontier that fish numbers have declined in the nearby Pun Hlaing River because of wastewater pollution from the distillery.

“Before 2010, there were a lot of hilsa and river catfish and we could cast a net near our village and be sure of a good catch,” Arkar Phyo said. “Since 2013 we haven’t caught any kind of such prized fish.”

A worker monitors smoke from the Yangon Distillery in Thaketa Township. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

Arkar Phyo said fishermen often had to dive into the river to free their nets if they became entangled on rocks or branches. He blamed untreated wastewater for the skin disorders he began suffering after the distillery went into operation.

“I suffered from itching for months,” he said, adding that not being able to enter the river had resulted in lower earnings from fishing.

U Kyaw Thu Tun, a member of a welfare association in Samalauk village tract, blamed years of inhaling atmospheric pollution from the distillery for the cancer that killed his father and two elderly monks from the adjoining monastery.

Following a campaign by the village community that had the support of regional MPs, the Ayeyarwady Region government recently ordered the distillery to suspend operations until it installed a biological treatment plant.

Arkar Phyo said that since the distillery had suspended operations many fish have already come back.

But the location of the distillery is also a problem for villagers.

“Even if the factory installs a proper treatment system, the villagers will not accept it and will continue to complain to the president and the state counsellor because it is situated in the middle of the village,” said Ayeyarwady Region Hluttaw lawmaker Daw Ni Ni Moe (NLD, Nyaungdon-1)

The Kyar Min Gyi distillery received its licence to make overproof alchohol under the military government in 2009. After the transition to democracy began in the aftermath of elections in 2010 won by the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party, the villagers began to voice opposition to the distillery.

A worker at the Yangon Distillery in Thaketa Township. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

U Kyaw San Naing, a director of the Environmental Conservation Department, agreed that the distillery’s location was unacceptable because it was in the middle of the village tract.

“We don’t instruct where these factories should be set up,” he said. “But we consider a lot for the location according to [Environmental Impact Assessment] regulations.”

Kyaw San Naing said distilleries licensed under previous governments would be the subject to departmental recommendations when they renewed the licences, as would companies applying for new licences.

But the final decision on whether to grant permission is up to the military-controlled Ministry of Home Affairs, he added.

Stricter enforcement

Yangon City Development Committee is planning to check that factories in the municipal area have installed effective wastewater treatment systems. There are 24 industrial zones with a total of 3,474 registered factories in the Yangon area but only about 10 percent have installed wastewater treatment systems, show YCDC figures.

The YCDC has five standards for wastewater treatment, depending on the type of factory, which include food and beverage manufacturers, chemical plants and battery makers, as well as distilleries.

A spokesperson for YCDC’s Pollution Control and Cleansing Department said that while the standards apply to more than 200 factories, only around 30 were meeting the requirements at present.

In an indication of the scale of the treatment challenge, the YCDC says 250 factories in a range of industries are producing 100,000 gallons of wastewater a day.

However, untreated wastewater from distilleries is particularly toxic and more poisonous than that from breweries, say experts.

Daw Aye Aye Thant, brewing team leader at Heineken Myanmar and a former executive at leading whisky brand Grand Royal, said huge volumes of water were needed to make overproof alcohol. “If you make 1,000 gallons of OP liquid, there will be 9,000 gallons of wastewater,” she said.

As the concerns of affected communities have risen, sympathetic MPs and groups such as Green Images Myanmar have been maintaining pressure on the government over the issue.

Nay Win hopes that factories will seize the opportunity to install effective wastewater treatment systems within the six-months set by the government.

“If we do not take action now,” he warned, “all of the rivers in Myanmar will be damaged by pollution and inland water fishery resources will be devastated.”

TOP PHOTO: A worker holds samples of wastewater at the Yangon Distillery in Thaketa Township, Yangon. The company installed a wastewater treatment system in 2015. The distillery opened in 2004. (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)