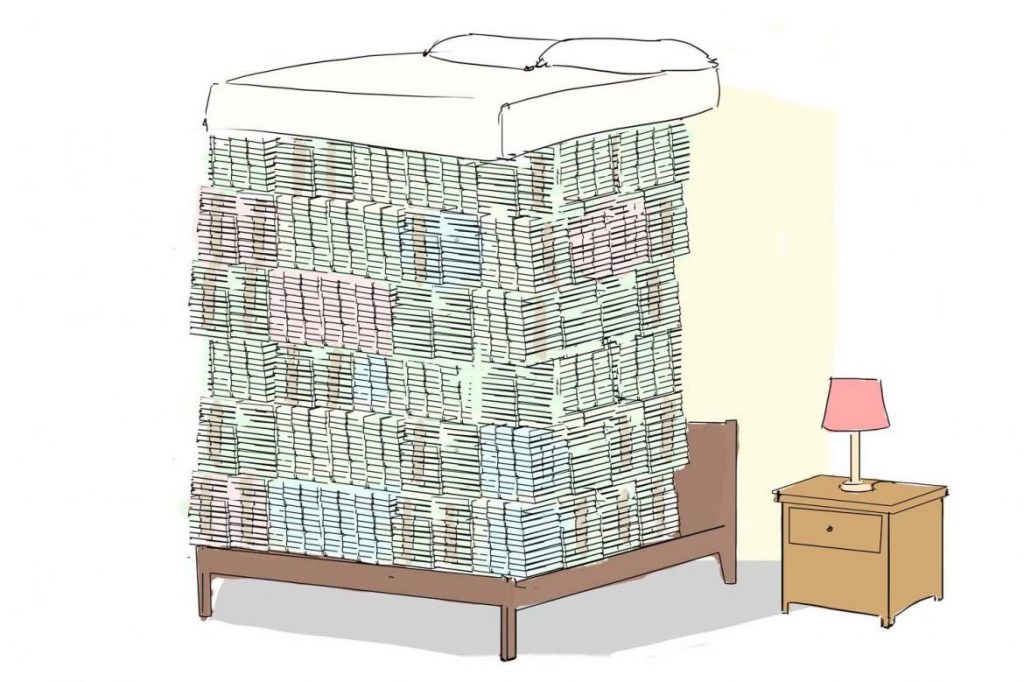

The numbers are startling. State-owned enterprises have K11.5 trillion (US$8.6 billion) in so-called “Other Accounts” at Myanmar Economic Bank.

THESE ACCOUNTS accrue no interest, costing the government hundreds of millions of dollars a year. Over the past three years, currency depreciation has meant the real value of these savings has likely declined by $2 billion.

To say that these savings could be put to better use would be an understatement.

We know all this thanks to a new report, State-owned Economic Enterprise Reform in Myanmar: The Case of Natural Resource Enterprises, that was released on July 10 by the Renaissance Institute and the Natural Resource Governance Institute. The authors spent 18 months analysing SOE finances and speaking to officials throughout the system to understand how it works. The picture is not pretty.

The Other Accounts numbers are attractive because they are an easy way to quantify the mismanagement of SOEs. But they are just a symptom of the real problem. Behind them lies an even darker, more tragic story – that of a startling lack of transparency and accountability at SOEs, from the top to the bottom.

Where auditing takes place, or expenses require higher approval, the process is nearly always just a rubber stamp. One example is expenses paid out of the Other Accounts: they are crosschecked to ensure that the figures add up, but there is no examination of what the money was actually used for.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The effects of this are clear when the report digs deeper into Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise. It reveals, for example, that under the terms of the contracts for Myanmar’s four offshore gas fields, MOGE is required to pay all taxes and duties except corporate income tax on behalf of the consortium, despite owning just 15 to 20 percent of these fields. As a result of these concessions, the country is likely missing out on revenues totalling hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

Onshore oil and gas fields are a black box. Many have no official data, including for revenues. Subcontracts for these fields are awarded by a three-person field management team, with no oversight. As well as lacking in transparency, onshore operations are also very inefficient and may in fact be losing money.

There are also unexplained costs at MOGE totalling hundreds of billions of kyat, and the strange situation whereby it has an outstanding loan of more than $1 billion from China at a relatively high interest rate of 4.5 percent, yet holds all this cash in its “Other Accounts” earning no interest.

It’s likely that other SOEs have similar problems, but at MOGE they are amplified because of the large sums of money that flow through the organisation.

These are legacy issues, some of which the government has little power to fix. It might not be possibly to renegotiate the terms of loans and tax arrangements. But the government can introduce enhanced oversight over SOEs to ensure that the ordinary people of Myanmar get the maximum possible benefit. This will take time.

One reason why the “Other Accounts” are important is because there is a quick fix: the government can amend the rules immediately, so that SOEs no longer retain 55 percent of profit.

It has the power to ensure that SOEs do not hoard huge amounts of cash. It has the power to ensure that revenues from state enterprises are paid into the treasury and put to the most productive use at budget time. It has the power to introduce greater transparency for expenses paid out of the Other Accounts.

It is incumbent on the government that this change is made now, in time for the next fiscal year beginning on October 1. Thanks to the work of Renaissance and NRGI, the disease has been analysed, diagnosed, pinpointed – now it’s time for the medicine.