The jump in reported child rape cases has resulted in more teenaged mothers and calls for a comprehensive response from the government.

By KYAW LIN HTOON | FRONTIER

THE ROOFTOP apartment in Yangon’s Sanchaung Township was welcoming with the fragrance of baby powder. There were babies and toddlers everywhere, some crying, some quietly enjoying each other’s company and others crawling on the floor.

The infants are residents of Mommy Cook, a maternity shelter for vulnerable pregnant woman. In the four years since it began providing care, Mommy Cook has helped hundreds of mothers. They include an increasing number of child mothers.

“At the moment I’m supporting 14 infants, ranging in age from two months to 18 months, and they include three children born to mothers aged between 12 and 15,” said Ma Shin Nyein Mel, 35, the founder of Mommy Cook.

A dramatic increase in child rape cases in Myanmar has focused attention on the crime and prompted calls for rapists to receive the death penalty. However, not enough attention is paid to the young victims, who receive support from a handful of NGOs, generous donors and activists. Most victims do not receive enough support or care from the government.

The numbers

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Ministry of Home Affairs figures show that there were 897 reported cases of child rape last year, up from 671 in 2016. The figures show that an average of two children are raped every day in Myanmar, but that’s based on reported cases and the actual figure is likely to be much higher.

Child rape is a distressing topic and cases make for uncomfortable reading.

One involves the five-year-old daughter from her second marriage of a woman we will call Daw Suu Wai Khin. In November 2016, in Yangon’s East Dagon Township her daughter was raped by her 18-year-old son from her first marriage.

Suu Wai Khin and her husband divorced over the incident. She did not believe her son committed the crime but her husband said DNA testing was submitted as evidence during the trial and on March 20 the son was sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment.

After her parents divorced and her father moved away, the victim wondered which parent to follow but she and an older brother, aged nine, eventually moved in with their mother. Difficulties finding accommodation meant they had to move three times in a year.

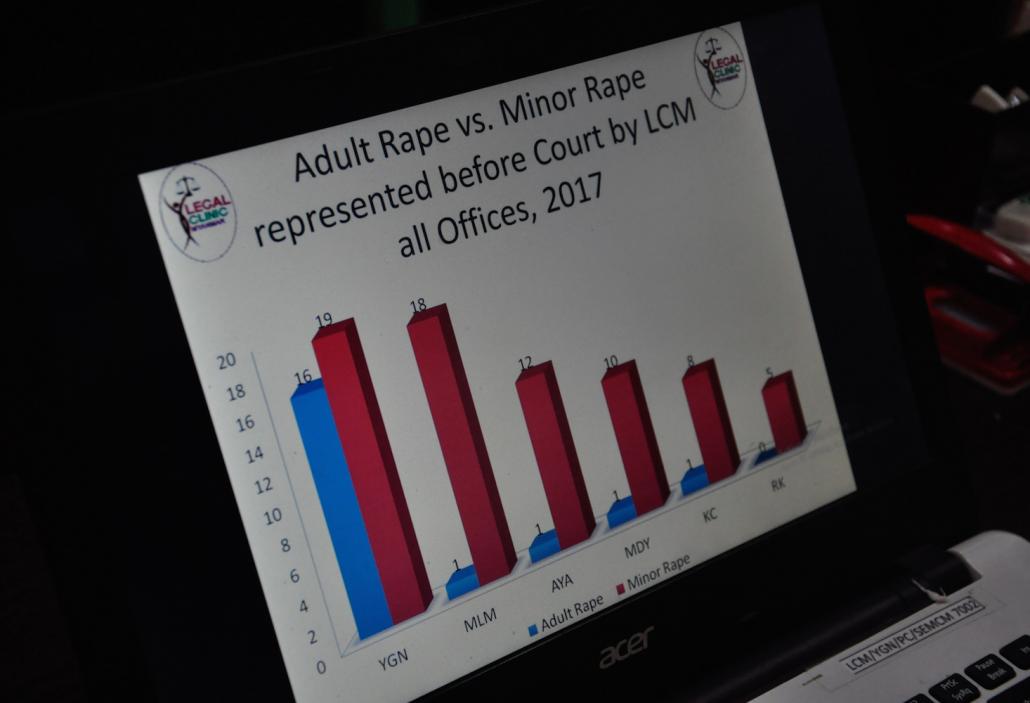

A screenshot of research on rape cases in Myanmar (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

Yangon Region MP U Nyi Nyi (National League for Democracy, South Dagon-1), learned of the case and has been doing what he can to help the victim’s family.

With the help of party members and friends, Nyi Nyi raised about K2.5 million to buy a small plot on which the family could build a house.

The victim, Phyu Phyu (not her real name), is a clever child who is making progress at kindergarten at a local public primary school.

Phyu Phyu, who underwent surgery at North Okkalapa Township Hospital to repair internal injuries suffered when she was raped, has set her ambitions high.

“I want to be a medical doctor and help people,” she told Frontier.

Victim blaming

A year before Phyu Phyu was raped, the four-year-old daughter of a woman we will call Ma Thiri Aung was allegedly raped by a monk at a Mandalay monastery where she was sheltering with her husband after they were evicted from their home by relatives over a dispute.

The monk had invited the couple to stay at the monastery while they saved enough to rent a house.

The alleged attack occurred about two months after the couple had been living at the monastery. They reported the alleged rape to the police, who opened a case against the monk and detained him. Instead of supporting the family, the community turned against it.

The monk’s wealthy followers began accusing Thiri Aung and her husband of lying about the rape to extort money. They had to leave the monastery and have since moved house four times.

“One of the previous house owners didn’t know about the rape case when we signed the rental agreement but after he heard about it we were evicted immediately,” Thiri Aung told Frontier.

In a neighbouring ward they rented a house from its kindly owner, but the attitude of local residents was hostile.

“When we moved into that ward, my daughter’s health was improving and she wanted to play with other kids in the street. But every time she tried to play with those kids their parents would order them to come home. Sometimes they even scolded their children in front of my daughter, telling them to never play with her again,” Thiri Aung said.

Daw Hla Hla Yee, a director of Legal Clinic Myanmar (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

She works part-time, as a cleaner and as a seamstress, and her husband works nights as a security guard. The cost of medical treatment for their daughter is a burden and attending trial hearings is also straining the family budget. Thiri Aung is grateful for donations of K300,000 from the Mandalay Journalism School and K50,000 from Legal Clinic Myanmar, which provides legal aid and social support to victims of injustice.

Thiri Aung said without the donations she would have struggled to cover the cost of medical care for her daughter, whose education over the past two years has been disrupted by complications arising from the physical injuries she suffered, as well as mental trauma.

Child mothers

The day before her interview with Frontier, Shin Nyein Mel was in Pyin Oo Lwin, where Mommy Cook has another shelter.

She was there to meet the family of a 12-year-old girl, who was seven months’ pregnant. The case was revealed when teachers became suspicious and a test confirmed the pregnancy. It’s alleged that the girl was raped many times by a cousin.

The girl’s parents were reluctant to file a complaint with the police and instead turned for help to Shin Nyein Mel, who has agreed to provide care.

The girl does not understand the changes taking place in her body and is afraid when the foetus moves. Her parents did not want the pregnancy to be terminated and they do not want to care for the baby after it is born.

“They want me to adopt the baby, and to care for their daughter,” said Sin Nyein Mel.

Women activists and specialists on sexual violence say it’s essential that the government provides better medical support and health care for child rape victims.

“State-owned hospitals should take account of all costs and provide the best possible care, from accommodation and medicine to communication,” said Ms Doira Lahkyen, a senior project manager with Paung Ku, an NGO that works to strengthen civil society groups.

“They [child rape victims] need to be provided with compassionate care,” she said, adding that they often require specialist treatment, such is the level of trauma they are often facing.

Calls for death penalty

The sharp increase in reported child rapes has fuelled a campaign for perpetrators to receive the death penalty.

Figures from Legal Clinic Myanmar underline the issue: it has received 72 requests for legal aid in cases involving the rape of children and 20 requests in cases involving adults, which is Myanmar is legally defined as someone aged 16.

child_rape_young_mothers_5.jpg

Children play in a room at the Mommy Cook centre in Yangon’s Sanchaung Township (Kyaw Lin Htoon | Frontier)

In January 2017, U Soe Nyunt, Justice of the Supreme Court, instructed judges to give heavy sentences to convicted child rapists.

On February 19, the Myanmar National Human Rights Commission released a statement urging the judiciary to impose heavy sentences on child rapists.

The calls came ahead of media reports that another 30 child rape cases were reported in the first quarter this year and that heavier prison sentences, of about 20 years, were being imposed on child rapists.

Despite the longer jail terms, calls for child rapists to be executed continue to grow.

Daw Hla Hla Yee, a director of Legal Clinic Myanmar, said that from her perspective as a lawyer it was unlikely that executing rapists would be an effective solution.

Capital punishment for child rapists could make the situation worse because perpetrators might be more likely to murder their victims, Hla Hla Yee told Frontier.

“If the parliament drafts a law that deals specifically with child rape, I would prefer it provides for paying compensation,” she said, adding that in the absence of any such law the government could issue guidelines that addressed the issue from prevention to rehabilitation.

Child welfare experts say the government needs to take a comprehensive approach, including ensuring that victims receive specialist medical care and trauma counseling, as well as providing more shelters.

Many of the victims’ families are poor, uneducated and vulnerable, and their lives have been badly disrupted by their ordeals. Yet, like Phyu Phyu, Thiri Aung’s daughter is also motivated to do well in her studies. She wants to become a lawyer.

“I want to send rapists to jail,” she told Frontier.