Learning Burmese is crucial to understanding the country better – so why do so few people learn it?

By BEN DUNANT | FRONTIER

“IT IS A common saying that you cannot pronounce Burmese properly till you take to betel-chewing,” wrote James George Scott, under the pen name Shway Yoe, in his 1882 collection of essays The Burman.

But in reality, this was another lame excuse for the Scottish-born educator, journalist and pioneering footballer. Teaching in a mission school in 1870s Rangoon, prior to his career as a colonial administrator, Scott learned Burmese quickly and was scornful of those less able.

From merchants to civil officers, “very few Englishmen learn Burmese, and still fewer speak it well,” he wrote. “There are not very many Englishmen who can properly appreciate the difference in sound between kyaung, a cat, and kyaung, a monastery. They are apt to lose their temper when the lesson is many times repeated.”

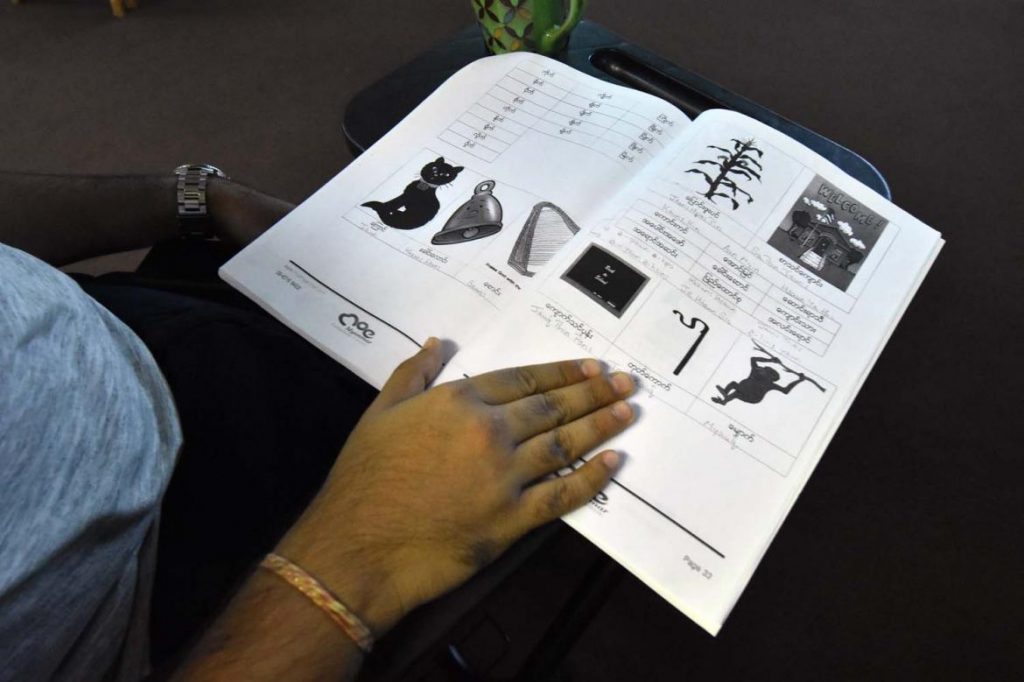

Though this was to improve in the course of British rule, fast forward 140 years to today and many among Yangon’s elite migrant community, from Europe and elsewhere, are unable to distinguish a cat from a monastery, writing from food, or a mountain from a basket, among other words that sound the same to those untrained in Burmese tones.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

For the casual visitor to Myanmar, the language gap appears manageable. Small talk with locals in English is easy to come by in the larger cities, and quickly learned Burmese phrases attract vigorous praise. But foreigners working in Myanmar will soon notice that, above a certain level of discourse, the Burmese and foreign staff of a given office inhabit different speech communities.

Burmese is the language of government, mainstream political activism, the majority of the media, and – despite the amount of colonial legislation in English still on the books – the law courts. It is the first language of about two-thirds of Myanmar’s population, and the second language of many among the rest, the country’s ethnic minorities who are generally denied education in their mother tongue. It is the only official language recognised in the constitution and remains the only viable link language across communities.

As a result, the foreign professional in Myanmar meets a crossroads early on. Either they commit the time, money and patience needed to learn what, in global terms, is an obscure language, or stay dependent on a limited corps of interpreters and translators whose skill and fidelity you can only guess at. Many, after several years in Myanmar, will find themselves frustratingly in the middle.

Yet, even proud polyglots struggle bitterly with the Burmese language, particularly if they are coming from a background of learning European languages. The soft distinction between vowel tones, the malleability of how consonants are voiced depending on syntax, and a grammar radically at odds with most Indo-European languages, require a degree of practice and immersion that few anticipate. There is also, relative to major Asian languages, a dearth of learning resources and a limited number of experienced teachers.

The Foreign Service Institute, which trains American diplomats, ranks Burmese among the second most difficult group of languages for native English speakers to learn, just below Arabic, Mandarin Chinese, Cantonese, Japanese and Korean. The British Foreign and Commonwealth Office ranks Burmese similarly.

But Professor Justin Watkins, a linguistics scholar who has taught Burmese at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies since 1999, says it is “meaningless to rank languages in terms of hardness. It gives people an excuse to feel that they’re doing something harder than anyone else.”

Ma Moe Chit teaches Burmese to two foreign students at the Moe Myanmar Language Centre. (Steve Tickner | Frontier)

For Watkins, the apparent difficulty of Burmese is a function of its distance from the first languages of many learners. “There’s an Orientalist angle to it, that Burmese is vague, Burmese is ambiguous,” he said. “It just means you haven’t understood how it works. You have to apply yourself and you don’t get it for free.”

Those who do apply themselves are effusive about the benefits Burmese proficiency grants to their work and lives in Myanmar.

Ms Vicky Bowman, who directs the Yangon-based Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business, was a second secretary to the British Embassy in Myanmar in the early 1990s before returning as ambassador in the early 2000s. She said a solid grounding in Burmese from the outset helped her gain access to different sides of a deeply divided society.

Her hobby of translating short stories and poems, including censored material, into English gave her “cover for meeting writers, artists and intellectuals who in the early 90s were about the only group still willing to talk a bit of politics”.

Her language skills also helped “break down barriers with the military on the few occasions I met them. They were usually scared to be seen speaking to a foreigner, but they couldn’t resist it when I spoke Burmese.”

Mr Ali Drummond, another British resident of Yangon who now does translation as part of his job with a French events company, studied Burmese at university in London but only became fluent after relocating to Myanmar in 2013.

“I immersed myself in Burmese society, isolated myself a bit from my expat friends, and hung out with a group of skateboarders,” he said.

He later helped establish an international-standard skateboarding park in a deprived area of Yangon by acting as a mediator between an international NGO, city authorities and the local skateboarding community, few of whom could communicate in English.

He said that, from his experience of mixed workplaces, knowing Burmese puts you in “a very advantageous position, sitting between foreign and local staff and knowing what each thinks of the other.” He added, “Burmese colleagues really value the fact that you can speak their language. It immediately sets you on a good relationship with them.”

For those without the language, interpreters and translators must bridge a gap whose length is seldom appreciated.

Ko Hein Naing Soe has worked for several years as an interpreter for international NGOs focusing on governance and elections in Myanmar. As such, he occupies a space where the English language is inseparable from a global expert knowledge base, which Myanmar has tried to tap into, in pursuit of reforms, after decades of isolation. He described the hazards of interpreting for foreign consultants who fly in and meet with Myanmar government officers, dispensing expertise acquired in another country.

The foreign expert can throw around concepts like “accountability” or “capacity building” and expect them to be translated effectively in a word or two. Hein Naing Soe said he can deploy Burmese neologisms – words or phrases coined, sometimes recently, to express such ideas in formal political discourse – but these often need to be accompanied by minutes of long-winded explanation to avoid confusion.

For instance, the term da wun khan hmu was popularised among government and civil society during the presidency of U Thein Sein to express “accountability”; but familiarity with the term still can’t be assumed, he said. Moreover, the term translates literally as “acceptance of duty” rather than submission to the law or public scrutiny.

But it works both ways. Many Burmese ethical concepts, expressed by words such as sedana, metta, thitsar and parami and rooted in Theravada Buddhism, don’t translate directly into English but are integral to mainstream social and political discourse.

Any discussion of the language gap, and its implications for political, economic, and social reform in Myanmar, might begin with a clearer picture of who these reforms are really for. Watkins believes it is important to shrink the privileged realm reserved for English in the exchange of important ideas, if the public isn’t going to be left behind.

“The amount of knowledge and power which is reserved for the English language speaking world here excludes people who happen not to be able to speak English because they don’t have money and go to a private school,” he said.

“I see it as being completely entrenched, because you can come and live here and do a high-powered job in an NGO or a company and not learn a single word of Burmese.”

But Bowman pointed to serious practical limits.

“Myanmar is not, in my view, an effective language for much professional discussion compared to English,” she said, pointing to “corporate governance” as an example.

“We have gone round and round trying to find a Burmese equivalent for ‘corporate’ to mean an organisational body that doesn’t have to be a business. We land back with ‘corporeiq’,” she said.

Nonetheless, according to Ma Moe Pwint, an experienced teacher of Burmese in Yangon, learning the language is the start of a more meaningful exchange between cultures: “When you learn a language, you don’t learn only the language but also the culture, and how people think.” She advises learners not to ask, “How do you translate this sentence into Burmese,” but rather, “What should I say in this situation?”

At a time when Myanmar and the international community hold diametrically opposed views on violence in Rakhine State and talk at cross-purposes about human rights and accountability, effective communication has never been so critical.

Learning to tell a cat from a monastery in Burmese may seem like a trivial milestone, but it’s a step towards what might one day be a more productive conversation between Myanmar and the world.