With the country’s power needs growing rapidly each year, hydropower is seen as a potential solution – but overcoming community opposition will be a formidable challenge.

By SU MYAT MON | FRONTIER

IN THE late afternoon, the residents of Shan Ywar village in Kayah State’s Loikaw Township sit and chat in front of their houses. Most are elderly or young, as the working-age adults have left to seek work in neighbouring Thailand.

Many of the 200 households in the village, in Loikaw’s Lawpita village tract, struggle to survive by growing corn on rain-fed fields. The past year has been particularly tough; corn prices have fallen sharply, from K400 a viss (1.6 kilograms) to K270.

At the current price, the average household’s production brings in just K2.2 million a year, said Sai Thein Zaw, a 100-household leader in the village. That would leave less than K200,000 a month to cover living expenses, not taking into account the cost of production.

“The falling price means that some people have not been able to sell their corn at all and they are really struggling,” he told Frontier last month.

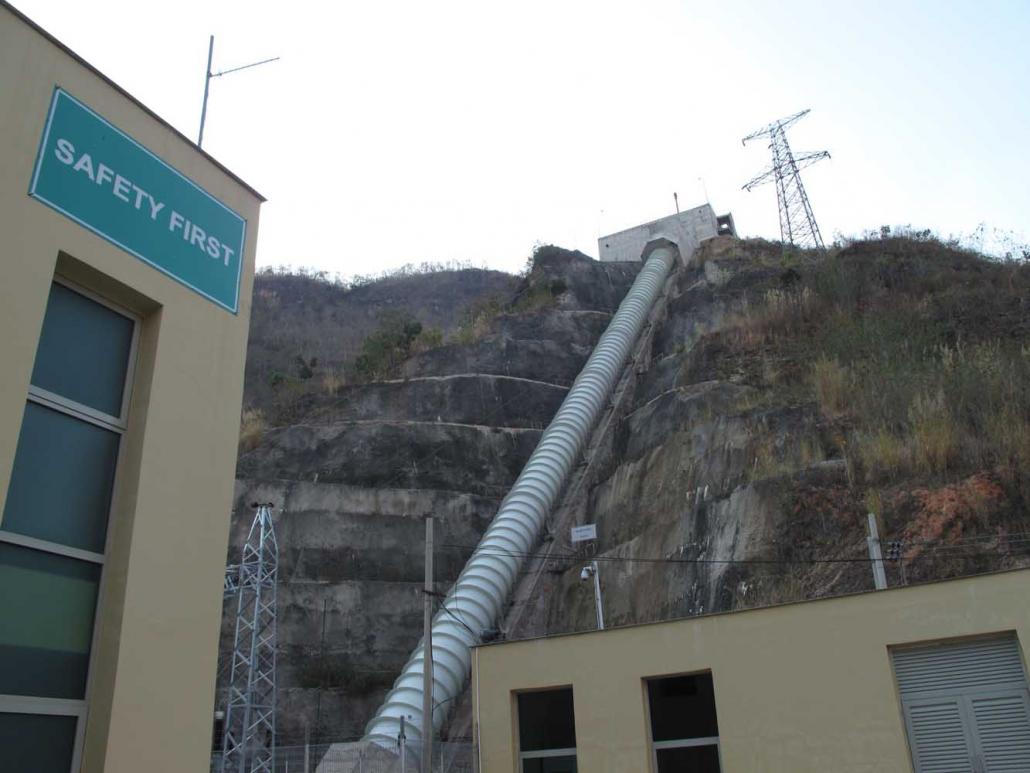

Despite the poverty and deprivation, the village is in the shadow of some of the country’s most important power-generating facilities: the three Baluchaung hydro plants.

The first in the cascade to be built was Baluchaung 2. Better known as Lawpita, it was constructed by the Japanese in the 1960s and 70s under a World War II reparation program and was Myanmar’s major power source for five decades. Today it generates around 5 percent of Myanmar’s electricity and mainly serves Yangon and Mandalay. Baluchaung 1 came online in the early 1990s and Shwe Taung Group completed the 52-megawatt Baluchaung 3 in 2015.

Power first arrived in Shan Ywar about 10 years ago, from Baluchaung 2. But many residents have only recently connected, because they didn’t have the money to pay the connection fee.

The development of the hydro dams has also resulted in much of the farmland in the area being confiscated, residents said, although they could not say exactly how much or when it was confiscated.

The construction of Baluchaung 1, about 4 kilometres (2.5 miles) from the village, has also affected their water supply. Now the river flows only during rainy season, according to Thein Zaw. At other times of the year, residents rely on a water pipeline from Baluchaung 1.

img_5231.jpg

title=

The supply is available for one hour every second day. Resident Aye Aye Myint said there are sometimes problems with the pipeline that result in it being shut down for up to a week. When that happens the villagers have to use a nearby stream to bathe and wash their clothes. “During the rainy season there are no problems but in the summer the shortages make it so difficult for us,” she said.

When Frontier visited Shan Ywar – as part of a media trip organised by the International Finance Corporation, a member of the World Bank Group – it was accompanied by U Aye Maung Maung, an executive engineer at Future Energy, the subsidiary of Shwe Taung Group that operates Baluchaung 3.

He often interrupted the interviews to provide responses, which made the residents hesitant to talk to journalists.

When Thein Zaw said there was not much farmland left since the projects were developed, the journalists asked why this was the case. Aye Maung Maung quickly cut Thein Zaw off, telling the journalists, “Well, the villagers said there is no farmland.”

The power gap

The desire – by some at least – to promote a positive image of hydropower development is indicative of the sector’s troubled history in Myanmar. This history, combined with a political environment in which ordinary people can now make their opinions heard, has made implementing new projects extremely difficult.

Few of the communities that are relocated for projects, or are otherwise affected by them, have seen the benefits. Most of the dams, either proposed or implemented, are in the country’s mountainous fringes, where poverty is high, ethnic armed groups are present and communities tend to be deeply suspicious of the government.

hydropower-map.jpg

/></p><p>U Ye Swe, deputy director of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation in Kayah State, conceded that winning community support for new dams was an uphill battle.</p><p>“The locals do not have enough knowledge about hydropower and their views are informed by the past, when they were treated badly for a long time. That is why they disagree with the projects,” he said.</p><p>Because of this opposition, people will need to “be patient and wait” for better electricity supply, he said.</p><p>But the country can hardly afford to wait. The government is aiming to have the country fully electrified by 2030 through a combination of grid expansion and off-grid solutions, bringing power to 7.2 million households and businesses, according to the World Bank. Energy demand is expected to rise by 10 to 15 percent a year as a result.</p><p>Big questions remain over the planned fuel mix to meet this energy challenge. The U Thein Sein government anticipated generating about 30 percent of electricity from coal by 2030, but the National League for Democracy-backed government has quietly shelved these projects. In September 2016, U Aung Ko Ko, director of hydro and renewable energy planning branch at the Ministry of Electricity and Energy, told Reuters that the government would instead increase the planned share of hydropower.</p><p>Hydropower already dominates Myanmar’s fuel mix; according to official figures, 26 stations with a combined installed capacity of 3,158 megawatts make up for around two-thirds of Myanmar’s total generation capacity. The government estimates there is potential for up to 100 gigawatts of hydro, and around 90 projects totalling 46 gigawatts have been identified as potentially be commercially viable.</p><p>About 50 projects have already been proposed, but many of these are in doubt because of community opposition, armed conflict, technical challenges and an inability to secure financing.</p><p>Ye Swe said that despite the challenges he believed that increasing the role of the hydropower was the best answer to meeting Myanmar’s energy needs.</p><p>“This is a good opportunity [to develop hydropower]. We really need power and foreign countries are will to provide technical support. We have to grab the chance firmly,” he said.</p><h3><strong>Charting a way forward</strong></h3><p>The question, then, is how to move at least some of the projects forward. To support decision-making, the International Finance Corporation is helping the government undertake a Strategic Environmental Assessment of the hydropower sector, focusing on five key river basins.</p><p>According to the IFC, which is part of the World Bank Group, the assessment will support high-level policy and planning by shifting thinking from a project-by-project basis to a “landscape approach”. Crucially, it will consider key environmental and social issues that have previously been ignored by planners and developers.</p><p>The assessment will result in a tool that maps out low, medium and high-risk areas for hydropower development on the river basins. For example, an area that is an environmental or cultural hotspot and also used for river transport or fisheries may be graded as a high-risk area because of the significant impact a hydro project would have. This tool can then be laid over proposed projects to guide planning decisions.</p><p>“At the moment, decision makers do not have a bird’s eye view of Myanmar’s river basins and a comprehensive document that outlines stakeholders’ environmental and social issues,” said Ms Kate Lazarus, the team leader for the IFC’s environmental and social hydropower advisory program.</p><p>“The government of Myanmar has an ambitious 2030 energy plan. As hydropower is part of the government’s master plan, we’re working to help the government raise standards and lower environmental and social risks and improve decision-making.”</p><h2 class=

/></p><p>The assessment is not project specific; while it will map the proposed projects, it will not make recommendations on whether they go ahead. It will also not replace the need for detailed environmental and social impact assessments for each project.</p><p>While the IFC has been involved in hydropower projects in other countries and supports sustainable hydro development, it is not involved in any projects in Myanmar. Lazarus said IFC would consider financing hydropower development once the strategic assessment is complete, but had no plan to get involved in “large hydropower development on the mainstream” of the Ayeyarwady and Thanlwin (Salween) rivers, such as the Myitsone or Mong Ton dams.</p><p>Nevertheless, the assessment will ultimately facilitate hydropower development. And that has put the IFC at loggerheads with many activists and communities that oppose dams at all costs.</p><h3><strong>Fiery meetings</strong></h3><p>The Strategic Environmental Assessment has included a series of stakeholder workshops across the country. These have served to highlight the extent of community opposition, particularly among political activists, to hydropower projects.</p><p>The workshop at the Kachin State capital Myitkyina in late January was picketed by about 60 protesters, who called for the cancellation of controversial projects on the Ayeyarwady River and its tributaries, including the 6000MW Myitsone.</p><p>At the February 3-4 consultation meeting in the Kayah State capital Loikaw, which Frontier attended, there was little interest in the nuances or scope of the assessment. Comments from the audience suggested that most in attendance were opposed to any hydropower development, and felt that the workshop was aimed at rubber-stamping existing hydropower projects.</p><p><strong></strong></p><h2 class=

title=

Officials from the Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Natural Resources and local activists engaged in at-times heated discussion.

The IFC representatives weren’t spared, either. When a presentation was given on fish species in the Thanlwin River, which is slated for more than half-a-dozen larger hydropower projects, activists interrupted with sarcastic comments.

They gave a range of reasons for opposing the projects, including the unfinished state of the peace process. U Oattra Aung, a member of Karenni National Youth Organization, said it was dangerous to proceed with hydropower projects in areas controlled by ethnic armed groups.

He said he was not opposed to all hydropower projects, but plans for dams on the Thanlwin needed to be carefully considered because they affected the rights of ethnic minorities, the peace process and the nation’s political situation.

It would be better if the peace process was completed before work continued on planned mega hydropower projects, he said, in an apparent reference to the planned Mong Ton Dam, which would be the biggest in Southeast Asia.

“We cannot accept this policy if it does not include our voice,” he told Frontier. “We did not come here just to listen to what their policy is; we came here to cooperate and make the policy together,” he said.

Ko Thein Zaw, a member of Mong Pan Youth Association, said developing hydro projects in sensitive areas now could harm the peace process and ethnic reconciliation.

He said the Thanlwin River was a sensitive and important place for ethnic minorities that live in its vicinity, and should not be desecrated by building dams.

He also questioned whether hydropower was necessary.

“If electricity can be produced through solar plants, then why are we looking at hydro power? And with these projects the electricity will be sold off to another country rather than used for our own country.

“We are not objecting the electricity project, but we do oppose the big dam project in the country.”

He said ethnic minorities also doubt whether they will benefit from the projects that are planned for their homelands. He noted that Nay Pyi Taw receives almost 24-hour electricity in part thanks to the dams in Kayah State, but Loikaw had only received a steady power supply very recently.

Officials said 63 percent of the state’s population now receives electricity, but activists retort that many villages were only connected shortly before the 2015 election, as the Thein Sein government sought to shore up its support.

“Where is the equality?” he asked. “We ethnic people do not think it is fair.”

Lazarus said the views of those opposed to hydropower development will be integrated into the strategic assessment, but also urged civil society not to oppose or boycott the process entirely.

“Hydropower is an emotive topic, especially in Myanmar where there is no history of projects that are best practice examples,” she said.

“We need civil society on board to help us raise standards and achieve sustainability. Working against the SEA means that one would be working against the idea of better understanding environmental and social concerns, or against the idea to help decision makers improve their planning.”

Additional reporting by Thomas Kean.

![/></p><p>U Ye Swe, deputy director of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation in Kayah State, conceded that winning community support for new dams was an uphill battle.</p><p>“The locals do not have enough knowledge about hydropower and their views are informed by the past, when they were treated badly for a long time. That is why they disagree with the projects,” he said.</p><p>Because of this opposition, people will need to “be patient and wait” for better electricity supply, he said.</p><p>But the country can hardly afford to wait. The government is aiming to have the country fully electrified by 2030 through a combination of grid expansion and off-grid solutions, bringing power to 7.2 million households and businesses, according to the World Bank. Energy demand is expected to rise by 10 to 15 percent a year as a result.</p><p>Big questions remain over the planned fuel mix to meet this energy challenge. The U Thein Sein government anticipated generating about 30 percent of electricity from coal by 2030, but the National League for Democracy-backed government has quietly shelved these projects. In September 2016, U Aung Ko Ko, director of hydro and renewable energy planning branch at the Ministry of Electricity and Energy, told Reuters that the government would instead increase the planned share of hydropower.</p><p>Hydropower already dominates Myanmar’s fuel mix; according to official figures, 26 stations with a combined installed capacity of 3,158 megawatts make up for around two-thirds of Myanmar’s total generation capacity. The government estimates there is potential for up to 100 gigawatts of hydro, and around 90 projects totalling 46 gigawatts have been identified as potentially be commercially viable.</p><p>About 50 projects have already been proposed, but many of these are in doubt because of community opposition, armed conflict, technical challenges and an inability to secure financing.</p><p>Ye Swe said that despite the challenges he believed that increasing the role of the hydropower was the best answer to meeting Myanmar’s energy needs.</p><p>“This is a good opportunity [to develop hydropower]. We really need power and foreign countries are will to provide technical support. We have to grab the chance firmly,” he said.</p><h3><strong>Charting a way forward</strong></h3><p>The question, then, is how to move at least some of the projects forward. To support decision-making, the International Finance Corporation is helping the government undertake a Strategic Environmental Assessment of the hydropower sector, focusing on five key river basins.</p><p>According to the IFC, which is part of the World Bank Group, the assessment will support high-level policy and planning by shifting thinking from a project-by-project basis to a “landscape approach”. Crucially, it will consider key environmental and social issues that have previously been ignored by planners and developers.</p><p>The assessment will result in a tool that maps out low, medium and high-risk areas for hydropower development on the river basins. For example, an area that is an environmental or cultural hotspot and also used for river transport or fisheries may be graded as a high-risk area because of the significant impact a hydro project would have. This tool can then be laid over proposed projects to guide planning decisions.</p><p>“At the moment, decision makers do not have a bird’s eye view of Myanmar’s river basins and a comprehensive document that outlines stakeholders’ environmental and social issues,” said Ms Kate Lazarus, the team leader for the IFC’s environmental and social hydropower advisory program.</p><p>“The government of Myanmar has an ambitious 2030 energy plan. As hydropower is part of the government’s master plan, we’re working to help the government raise standards and lower environmental and social risks and improve decision-making.”</p><h2 class=](/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/hydropower-map.jpg)