The AA’s offensives into neighbouring regions together with its resistance allies have brought Myanmar’s civil war to new corners of the country – and put the group within striking distance of key munitions factories.

By FRONTIER

In March, Myanmar’s civil war finally came to U Sein Myint’s village in Lemyethna Township.

Residents of nearby farming communities began fleeing military airstrikes, as regime forces sought to push back Arakan Army troops advancing into this normally quiet corner of northwestern Ayeyarwady Region.

Sein Myint, who requested the use of a pseudonym to protect his identity, knew it was only a matter of time until the bombs also began raining down on the home he shared with his brother and sister in Pan Taw Gyi, a village on the Pathein-Monywa highway about 130 kilometres’ drive north of the region’s capital Pathein.

With the fighting edging closer by the day, they took the difficult decision to leave. “We could tell the situation was getting worse, so at the beginning of April, before Thingyan, we went and stayed with a friend in Hinthada” located about 60km east of Pan Taw Gyi, he said.

It turned out to be the right decision. Less than two weeks later, the village was hit by airstrikes and artillery fire, burning some houses and forcing the remaining residents to flee. “I heard our house wasn’t damaged, but I haven’t been able to go back and see it for myself, so I’m not sure,” Sein Myint told Frontier in late April.

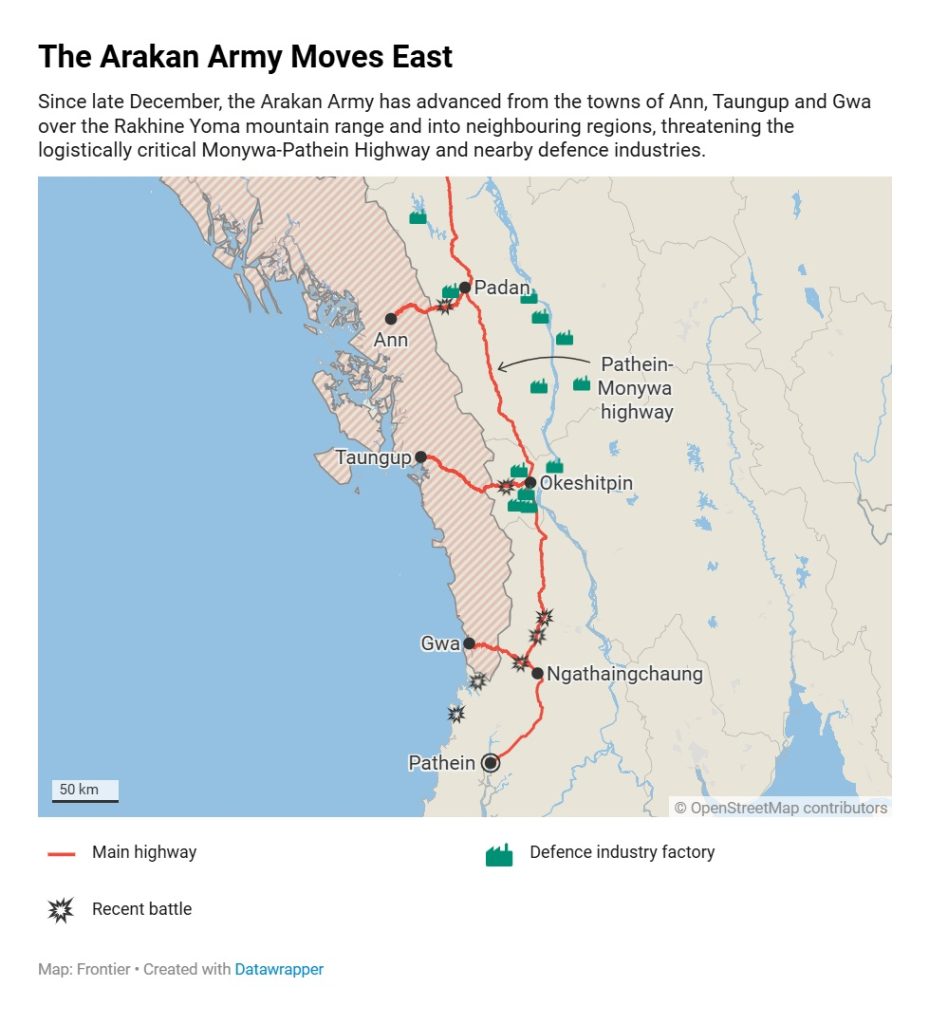

The AA offensive into Ayeyarwady followed the group’s capture of Gwa Township in late December. After seizing the southernmost part of Rakhine State, AA forces began pushing over the foothills of the Rakhine Yoma mountain range into the delta, thrusting east into Yegyi Township, and south into Pathein Township.

The AA has since attacked numerous points along the Pathein-Monywa highway, a 750-kilometre two-lane road that runs north-south between the Rakhine Yoma and the west bank of the Ayeyarwady River. The military has responded by increasing security and restricting traffic flows, as it seeks to retain control of the critically important route.

The clashes in Ayeyarwady have created difficulties for residents who have stayed behind, a young man from Si Kwin village in Lemyethna Township told Frontier.

“There’s been fighting on both sides of the Pathein-Monywa highway. There hasn’t been any fighting in our village yet, but because of the clashes we can’t go to Lemyethna or Ngathaingchaung [towns] to buy essential goods,” he said. “It’s not so bad for people who have money – they stocked up when we heard the war was coming. But for day labourers like me, a long conflict is going to cause a lot of problems.”

While the fighting is still mainly confined to the fringes of Ayeyarwady, its consequences are being felt in the region’s urban centres. Some displaced people have sought refuge in Hinthada, a town of around 100,000 people on the west bank of the Ayeyarwady River.

“There are now many people here who have fled the war. Some stay with close friends, relatives or acquaintances, but it seems renting is the more common option,” said Hinthada resident U Soe Thein, who runs a small business selling peanut oil. “We don’t know when the fighting will reach our town, so we live cautiously and try to save whatever we can.”

Three-pronged attack

The Ayeyarwady attacks are part of a three-pronged AA offensive beyond the borders of Rakhine into neighbouring regions. The group’s forces have also moved from Taungup Township into Bago Region’s Padaung Township, and from Ann Township into Magway Region’s Ngape Township.

On January 26, the AA captured the regime’s Moehtitaung camp, on the border between Rakhine and Bago. It took the group another two months to advance beyond the heavily fortified Nyaung Cho military base, about 15 kilometres farther along the mountain highway, but its capture has cleared the way for AA forces to push down the mountains towards the west bank of the Ayeyarwady River.

Thousands of residents have fled in anticipation of further fighting. Bago-based resistance forces told Frontier that clashes were continuing between the military council and revolutionary forces in western Bago. “It appears the military council’s forces are undergoing some form of preparation or repositioning,” a Gyobingauk People’s Defence Force spokesperson said. “We’ve observed them withdrawing from smaller outposts, which suggests they may be reorganising their operations.”

“People from Nyaung Cho and Nyaung Chayhtauk villages have fled and taken refuge in the towns of Padaung, Okeshitpin and Pyay to escape the war,” said a spokesperson for the National Unity Government’s Bago Region Military Department, Pyay District, Battalion 3602.

A woman from Padaung Township, who fled the war to Pyay town, said her family has been on the run since March. “We’re renting a house and still living off the money we brought with us. If it takes too long to return home, I’ll need to find a job here though. I don’t really understand the fighting, I just know that I want to go home as soon as possible,” she said.

Farther north, AA forces have advanced along the Ann-Padan road over the Rakhine Yoma into Magway since taking Ann and the military’s Western Command headquarters in December, but seem to be bogged down in fighting around the heavily fortified Nat Yay Kan military base in Ngape Township.

A senior official from the People’s Independence Army, which is supporting the AA offensive, said Nat Yay Kan was the “key entry point” to the region, and its capture would “make it easier for revolutionary groups to move into and operate freely throughout Magway”.

“The fighting is intense – the military is fiercely resisting and defending this position, and reinforcing as much as it can,” said Ko Moe Nay La, a member of the PIA’s central committee. “There has also been fighting along the military’s supply lines, as resistance forces attempt to cut off their logistical support.”

Salai Khani Lay Bway, a spokesman for the Asho Chin Defence Force, which has been supporting the AA operation, said the fighting had displaced more than 2,000 people from 13 villages in Ngape. “Right now, the fighting is focused on mountainous areas of Ngape Township – the people fleeing are from that area,” he said.

In Magway’s Mindon Township, which lies between Ngape to the north and Padaung to the south, the situation remains calm, said Ko Ba Hein, who leads the township’s People’s Defence Team.

However, the military has stepped up security along the Pathein-Monywa highway, which runs through the centre of the township and is an important logistical route.

“The military council has blocked the roads to prevent supplies from reaching areas where resistance forces have established footholds west of the Pathein-Monywa road. Military council camps are scattered along the road, and they are deploying a significant number of troops to maintain control over this section,” he said.

The highway is integral to the functioning of the military’s defence industries, most of which are on the west bank of the Ayeyarwady River in Bago and Magway, according to a January 2023 report by the Special Advisory Council-Myanmar.

The report says the factories were concentrated in these regions because they had historically been under firm military control and dominated by Bamar Buddhists, who it perceived as less of a threat than ethnic minority peoples.

The military seems to have never envisaged the possibility of a partnership between ethnic and Bamar forces that could threaten its grip on the Ayeyarwady’s west bank – precisely the prospect it now faces.

Building alliances

For almost 18 months after the coup, the AA avoided confronting the military, instead focusing on consolidating control in rural areas of Rakhine. Publicly, the group gave the impression that it had little interest in supporting the broader revolutionary movement against the regime.

Quietly, however, the AA was providing training and weapons to resistance groups that had sprung up on the border of Rakhine. Each April, when the AA marks its anniversary, more and more resistance groups send it messages of appreciation, including several groups from Magway.

In a statement this year, the PIA thanked the Rakhine group for not only providing them with training but also “instilling the patience, perseverance and spirit of sacrifice essential to the revolutionary journey”, adding that it stands ready to support the AA in whatever capacity it can.

Some of these groups supported the AA’s offensive on the Western Command in Ann, either by fighting directly or ambushing regime reinforcements as they travelled along the Ann-Padan road towards Rakhine. “Since Operation 1027, most of our efforts have focused on the Rakhine front, where we’ve been fighting alongside allied forces,” said Moe Nay La from the PIA, referring to the offensive launched in northern Shan State in October 2023 by the Three Brotherhood Alliance of ethnic armed groups, to which the AA belongs.

This strategy now appears to be paying further dividends for the AA as it advances into neighbouring regions, where these groups are based.

But there is limited information on the exact division of labour between the AA and its allies. The Rakhine group continues to say little about its cooperation with resistance forces; spokesperson Khaing Thu Kha did not respond to Frontier’s requests for comment.

Moe Nay La from the PIA said it was a “mutually beneficial relationship” built on respect and kindness. “When kindness is shown, it should be reciprocated. … We will do our best to support the AA with all our abilities and resources,” he said.

Most other resistance groups in Ayeyarwady, Bago and Magway that have ties to the AA also declined to comment when contacted by Frontier. Comrade Kaung Kyaw from the NUG’s Regional Military Command of Ayeyarwady acknowledged the group’s alliance with the AA but said he could not discuss it further “due to restrictions arising from our arrangement with our allies”.

A member of the People’s Liberation Army, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said the AA had been an important partner for armed groups across the country, not only on the fringes of Rakhine.

“They’ve launched supporting attacks in areas controlled by the Karen National Union, and they’ve also taken part in the fighting in northern Shan State. Whether it’s the PDFs or other groups, the AA has provided training when they’ve needed it,” she said. “When they achieve victories, it feels like our own victories as well. I truly want to see them succeed. I believe they’ll continue supporting the revolutionary forces as much as they can.”

A political analyst told Frontier on condition of anonymity that China’s intervention in Myanmar in the second half of last year to shore up the regime from potential defeat meant the AA and its allies had to be circumspect about their objectives and cooperation.

“[AA and revolutionary forces] are being cautious because they can’t clearly and directly state their objectives,” the analyst said. “It’s possible that because of Chinese pressure the AA might have to stop its military operations – like the [Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army] did – and instead negotiate political concessions for Rakhine State with the military council. That’s why they are avoiding giving open and direct answers to the media.”

U Pe Than, a former Arakan National Party lawmaker, said the AA had built alliances with resistance groups across the country, providing them with training and enabling them to gain combat experience. “This isn’t just to build their capabilities in the current fight – it’s also to prepare them to take on greater responsibilities in the mainland,” he said. “From what I see, it’s a deliberate and strategic move to build a stronger, more coordinated resistance front nationwide.”

A mixed welcome

While the AA’s resistance partners are effusive in their praise, the same cannot be said for some residents of western Ayeyarwady, Bago and Magway. Until the AA-led offensives, these areas had seen few clashes, largely insulating locals from the worst of the country’s civil war. “Sometimes we would hear reports of PDF groups targeting and assassinating military council officials, such as administrators or Pyusawhti members. But actual fighting only began recently,” said a Padaung resident.

The AA’s forays into these majority Bamar lowland areas have therefore generated a mixed response. Some told Frontier they hoped that the AA could work with resistance forces to overthrow the regime.

“I welcome the AA’s presence in Ayeyarwady. If the fighting reaches our town and we have to flee, then so be it,” said Soe Thein, the Hinthada resident. “People in the towns really despise the military, especially due to its conscription policy. They only deal with the authorities when absolutely necessary.”

A man from Padaung Township who recently fled to Pyay to escape the fighting said he didn’t blame the AA for his predicament. “The AA is joining in the revolution against military dictatorship. Yes, we’re suffering a lot because of the war, but the main reason people are suffering is because of the military coup,” he said. “I don’t want war or to have to flee my home, but if it happens then I’ll just face it. My only view on the AA entering Magway is positive because they’re fighting the military council.”

Not everyone is so supportive. Others said that while they hated the regime, they were worried about the toll the fighting would inevitably take.

“I don’t want to say anything about the AA’s presence here in Ayeyarwady – I just want this fighting to end quickly so that we can work and live in peace,” said a Lemyethna Township resident who recently fled his home. He said the military’s air superiority would make it difficult for any opposition force to defeat the regime. “As long as they can’t defend against the regime’s air attacks, then civilians will continue to suffer and die. … The only way for the conflict to end soon will be some kind of negotiation between the sides,” he said.

A woman who recently fled fighting in Padaung Township said she doesn’t support “any group that causes us suffering – not the AA, not the resistance forces, and certainly not the military”.

“To have to flee my home and farmland like this … sometimes I wonder what kind of bad karma I must be paying for,” she said. “I can’t even think about the future – I have no idea what to do, how to make a living right now. … All we want is to live in peace.”

Eyeing the end game

The AA push over the mountains has raised questions about the group’s objectives, and how far they plan to extend beyond Rakhine. Analysts and observers agree that the AA wants to establish a buffer zone around the state, and ensure firm control over the three highways that link it with central Myanmar.

Beyond that, there are a few obvious targets, such as the almost two dozen munitions factories run by the Directorate of Defence Industries – often referred to by its Burmese acronym KaPaSa – in Magway and Bago. The fighting is already approaching some of these factories, including a cluster of five plants near Okeshitpin in Padaung Township that produce bullets, gunpowder, cordite, mortars and anti-aircraft rockets.

“The AA will attack the KaPaSa factories – that much is certain,” said Pe Than. “It’s necessary for the entire country, for the revolution.”

The PLA fighter agreed that the munitions factories were an important objective. “If resistance forces can take these factories out of commission, it could significantly weaken the regime’s grip – not just in Magway and Bago, but even in Yangon and Nay Pyi Taw. The end goal of the revolution could be within reach,” she said.

But she believes the AA also wants to support resistance forces so they can take the fight up to the regime in majority Bamar regions. “I really believe their actions will contribute to the liberation of the entire country,” she said.

Most locals told Frontier they did not think the AA would advance its own forces into central Myanmar to topple the military regime, and that the group might eventually reach a ceasefire with the military. But they said they believed the group would continue helping resistance forces take on the regime.

“I think [the AA is] expanding gradually on this side of the mountains to better defend their territory in Rakhine,” said a resident of Okeshitpin. “Eventually, they might engage in negotiations with the junta, similar to the [MNDAA] … but I think they’ll keep participating in the revolution until it is successful, such as by supporting revolutionary forces with weapons and military training.”

A Magway resident echoed these comments, saying he believes the AA will continue supporting its resistance partners even if it begins negotiations with the regime. “I don’t think they’ll betray the people of the mainland – they’ll continue supporting revolutionary forces until the revolution succeeds. They understand that the junta is not good,” he said.

Pe Than said that while negotiations might take place, the AA ultimately saw little alternative to defeating the military regime. “The group’s main objective is not just to defend Rakhine State,” he said, “but also to join forces with allies across the country to fight until the military dictatorship is completely defeated.”

For Sein Myint, who fled his home in Lemyethna Township in March, the end of the fighting can’t come soon enough. He blames the military rather than the AA for his predicament but is nevertheless worried about what the future might hold.

“I just want the revolution to end as soon as possible,” he said. “The longer it drags on, the more civilians suffer and lose everything.”