The overstretched military is increasingly recruiting young men in urban areas against their will, often targeting them at night and threatening them with imprisonment.

By FRONTIER

On the night of October 27 in the Mon State capital of Mawlamyine, a truck full of soldiers stopped Ko Wai Phyo* on his motorbike. The 19-year-old was returning home from watching a football match at a teashop, but before he could explain this, the soldiers shoved both him and his bike into the truck and drove off.

Luckily a neighbour, U Soe Kyaw*, witnessed the scene. “When I saw him being taken away by soldiers in a truck, I rushed to tell his parents. Then some people from the ward and I accompanied them to the police station to find him,” he told Frontier.

By then, it was late into the night and they were told to return the next morning.

“We went back to the police station at 7am, but he wasn’t there. The police told us they hadn’t arrested him and he was probably in a military compound. They said they would make inquiries and asked us to go home,” Soe Kyaw said.

That afternoon, the police phoned Wai Phyo’s parents, telling them their son was being held at a military recruitment office in the Southern Command compound outside of town. But although difficult, his release was negotiable.

“The police told us they would make arrangements with the military, but they’d have to find a replacement for Ko Wai Phyo and they’d need some money. They said that we had to pay K3 million [about US$880 at the market rate],” Soe Kyaw said.

As a former ward administrator, Soe Kyaw knew how to deal with authorities. He advised the parents to pay the requested amount and Wai Phyo was released.

Wai Phyo was lucky to escape from the military’s clutches, but he was brutally beaten on the night of his detention and an army officer told him he had to choose between joining the military or going to prison. He also wasn’t alone.

“I saw about 30 young men who were detained like me. They couldn’t alert their families because they’d been taken so suddenly. If no one had witnessed my arrest I’d be a soldier now,” Wai Phyo told Frontier from Thailand, where his mother had sent him to live with an aunt after the incident.

“They asked us to choose between going to prison for three months or joining the military, and they beat us up when we said we wanted to go home. I was lucky because my parents managed to release me the next day. But the military asked me to sign a letter pledging I wouldn’t talk about what happened to me and threatened to arrest me if I did,” he said.

Nonetheless, Wai Phyo decided to inform the families of those he had met at the military compound.

“It was difficult at first because I couldn’t remember the names and addresses, but soon after I got out, I saw missing persons notices and I advised the families to look for them at the military recruitment office,” he said.

Desperate measures

The Tatmadaw has reportedly struggled to recruit enough new soldiers since the 2021 coup and its brutal crackdown on the popular uprising against its rule. Increasingly overstretched by nationwide armed resistance, it has turned to seemingly desperate measures like sending jailed deserters back to the front lines and forcible recruitment in rural areas via a lottery system.

As reported by Frontier in 2022, men whose names were drawn in these lotteries had to enter the army or pay a fine that was beyond what many of their families could afford. In February of that year, junta chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing said in a speech to senior officers that every citizen has a responsibility to serve in the military for two or three years under the People’s Military Service Law. Enacted in 2010, it says men aged 18-35 and women aged 18-27 are required to serve for up to two years, while those chosen as technicians and experts must do up to three years. But despite this law being in effect for more than a decade, there has been no formal conscription programme, and instances of forced recruitment recorded by Frontier were undertaken without reference to the law.

Conscription via the lottery system had prompted rural families to move to cities, where they imagined their male members would be safe. However, since at least late October this year, the military has begun forcibly recruiting in some urban centres – a practice resurrected from the time of the last junta, before 2011.

Although the extent of recruitment is unclear, reports have spread on social media of men being detained and forced to join the army even in Yangon, Myanmar’s commercial capital, prompting warnings to avoid going out at night in the city.

The recruitment drive has likely been spurred by the offensive, codenamed Operation 1027, launched by the Three Brotherhood Alliance of ethnic armed groups in northern Shan State on October 27. The Brotherhood caught the Tatmadaw by surprise and seized about 200 military outposts near the border with China in the initial weeks of the offensive. Operation 1027 also galvanised the resistance elsewhere in the country, inspiring similar offensives in Kayah and Chin states and Sagaing Region.

Meanwhile, the regime has denied it’s forcibly recruiting soldiers or people to act as porters. “There is no reason for the military to do any of this anywhere in Myanmar… I want to inform the public that they can live in peace,” junta spokesperson Major-General Zaw Min Tun said on November 23.

However, the Rangoon Scout Network, a group dedicated to gathering and publicly sharing information on the security forces’ movements in Yangon, paints a different picture. The group documented 95 cases of people being detained and taken in military vehicles from the last week of October to December 18 in Yangon Region.

One of them is Ko Win Kyaw*. The 34-year-old man was seized by the military in Kamaryut Township on the night of November 14 when he was walking home from a friend’s house.

“It was around 12:30am and they arrested me saying I was hiding in the dark. They took me with eight other men. We were beaten in a military truck and then taken to a police station. My wife and a friend found out the next day and went there,” he told Frontier.

Win Kyaw was told he’d have to join the military but was released after his loved ones paid K500,000. “The men arrested with me were kept in the cells and I don’t know what happened to them,” said Win Kyaw, who has been living in hiding since then.

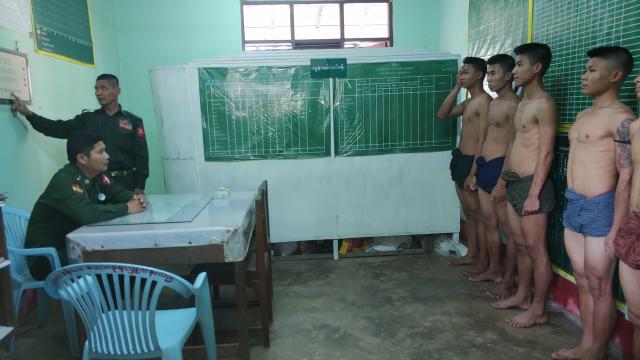

Child soldiers

The Tatmadaw has also allegedly recruited minors, with the United Nations documenting 112 cases last year. However, other armed groups, both aligned with the junta and opposing it, have also used child soldiers, defined as being younger than 18, with the UN documenting a total of 235 such cases.

One of those conscripted by the military was Ko Aung Kyaw*, who was taken in Sagaing in October 2022, aged 16.

“I left home because I didn’t have a good relationship with my father. My parents divorced when I was a kid. I left my father’s house in Mingin Township to find my mother. But I was arrested near Mingin town, where she lives,” he told Frontier.

Like many minors in Myanmar, Aung Kyaw didn’t yet have a national ID card, and his captors used that against him.

“The soldiers took me to the local police station and left me there the whole night. They came the next day and interrogated me. They asked me if I had a national registration card and I told them I didn’t because I wasn’t 18 years old yet. They asked me what other documents I had, but I didn’t have any,” he said.

That’s when he was threatened into becoming a soldier.

“One officer told me that I should join the army if I didn’t want to go to prison. I replied that I didn’t want to join the army. He said I’d be in prison for more than 10 years, but if I joined the military, I could live well,” he said.

Aung Kyaw was eventually sent to a recruitment unit in Magway town and after five months of training, in April last year, he was deployed in southern Shan’s Pekon Township, a place of active conflict between the military and largely Karenni resistance forces.

Seven months later, he managed to contact the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force and the resistance group helped him flee from his base into their sanctuary.

“There are a lot of soldiers who were forcibly recruited like me. They are also waiting for an opportunity to escape,” Aung Kyaw said from Thailand, where he now lives in hiding.

*indicates the use of a pseudonym for security reasons