A health sector strike and an uneven public boycott of coronavirus jabs under the military regime has made even Myanmar’s modest vaccination goals seem delusional.

By FRONTIER

At 68, Daw Shwe Yin Aye is among the 3.6 million people aged over 65 that the deposed National League for Democracy government prioritised for a COVID-19 vaccine.

She received the first of two doses on February 5, when it first became available at the Basic Education High School No. 4 in her township of Botahtaung, in Yangon. High schools in the city’s Dagon and Pabedan townships also began administering jabs that day.

“It was painless and I’ve had no side effects,” she told Frontier at the time.

On December 11, State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi took to the airwaves to promise that no one would be left behind in the government’s COVID-19 vaccination programme, which aimed to first vaccinate frontline health workers and those aged over 65, followed by people with underlying health conditions and senior government staff.

“I’m deeply thankful to the State Counsellor, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, and her elected civilian government for covering all citizens with the COVID-19 vaccination programme,” Shwe Yin Aye said. “We’ve got a precious opportunity to be vaccinated because of [Aung San Suu Kyi’s] efforts.”

Health workers administer COVID-19 jabs in Botahtaung Township’s Basic Education High School No. 4 in Yangon on February 5. (Frontier)

For many others, however, the ousting of Aung San Suu Kyi’s government in the February 1 military coup has changed their entire attitude to the vaccination programme. The frontline health workers that were also prioritised for the first jabs have refused them en masse so long as they’re being administered by a reviled military junta. Those workers spearheaded the Civil Disobedience Movement in early February by walking off jobs at state hospitals and healthcare facilities across the country, bringing the junta’s entire COVID-19 response to a virtual standstill.

The military regime is still trying to get the 3.5 million doses of Covishield – the Serum Institute of India-made vaccine based on Oxford-AstraZeneca’s, which the NLD government acquired in late January – into people’s arms, but with anger and distrust at the regime so widespread, people are increasingly refusing the jabs.

And while junta health officials say they have the capacity and cold chain technology to safely store all these doses and more, health officials told Frontier they could expire in the next one to two months. Although India’s drug regulator at the end of March increased the expiry period of Covishield doses from six to nine months, the Serum Institute began manufacturing the vaccine around October last year, and Frontier could not confirm when Myanmar’s batch was produced.

Myanmar offers perhaps the starkest example of a global trend. Even in places where early COVID-19 responses were exemplar, such as Hong Kong, distrust in government is threatening vaccine rollouts. And while in the United States, the vaccine rollout under President Joe Biden has been notably quick, distrust and conspiracy theories among a polarised electorate are still hampering the process.

It’s a dramatic lesson in how central trust is to effective governance, and perhaps never more so than in the midst of a pandemic. The junta now appears set to preside over millions of potentially spoiling vaccines and an inoculation programme that, at its present rate, would take many years.

Health offices shuttered

All told, more than 8,000 seniors turned up for their first jabs in the three Yangon townships on February 5. While impressive, it’s a small fraction of those eligible, with some 380,000 people aged 65 or older living in Yangon Region.

After March 11, jabs for these seniors were expanded to health departments and high schools in 19 other townships in Yangon Region. Residents in several of these townships told Frontier that, after few people showed up, many of the facilities began offering the jabs to anyone over 18 who presented valid identification.

Walking the streets of Yangon, it is not hard to find people even in the most vulnerable demographics who refuse to be vaccinated while the military remains in power.

“Even health workers who have been fighting on the frontline to control COVID-19 have boycotted their second jabs, so I too will never be vaccinated [under this regime],” Daw Thein Oo, a 69-year-old Thingangyun Township resident, told Frontier on March 31. “I will get vaccinated only if the elected, civilian government returns to power.”

Dr Khin Khin Gyi, director for emerging infectious diseases at the Ministry of Health and Sport’s Central Epidemiology Unit, is frustrated by this reaction. She stressed that the vaccines were acquired by the NLD government, not by the junta, and said getting the population vaccinated remains an important goal despite the political situation.

“I do not want people to miss out on the opportunity to get vaccinated, because these vaccines … are owned by the people,” she told Frontier. “All citizens have a right to this vaccine supply.”

She said she’s worried about the current supply expiring.

No public health officials Frontier spoke to could offer an estimate of how many people have received the initial jab in the Yangon townships that offered them, but several have since had to close their nascent vaccine programmes due to labour shortages caused by the CDM. On March 26, the health ministry pleaded on its Facebook page for striking healthcare workers to return to work and help conduct COVID vaccinations for the public.

A health worker administers first doses of the Covishield COVID-19 vaccine to seniors at the Botahtaung Basic Education High School No. 4 in Yangon on February 5. (Frontier)

The more than 8,000 that received their jabs on February 5 initially had their second shot scheduled for March 5, but the CDM has so crippled the ministry’s operations that second jabs have widely been postponed, with several local medical offices forced shut. The ministry has not set another date, except to say second jabs will be available sometime after the Thingyan traditional new year holiday, which is in mid-April.

On March 31, Frontier visited Botahtaung’s township health office on the upper block of 46th Street, but the building was closed for construction. A nearby mohinga vendor said the department had moved to the lower block of 42nd Street, but when Frontier arrived there, that office was also closed. A nearby resident said it hadn’t been open for the past month.

Another said their 70-year-old mother had received her first shot at the high school on February 5 but has not received her second, nor any information from any level of government on when she might expect to.

When Frontier arrived at the health department in Dagon Township, that office was also closed.

A staffer there that Frontier had previously spoken to said the office was too short-staffed to administer second doses, and that each ward administrator in the township will have to make their own decision on when the second jabs will be available in their neighbourhoods – probably sometime after Thingyan, he added.

“We cannot mobilise the manpower yet,” he said.

Repeated phone calls seeking comment from both Dr Daw Zin Min Min Latt and Dr U Shwe Pyi, the township medical officers for Botahtaung and Dagon, respectively, went unanswered.

From prioritisation to free-for-all

A former COVID-19 treatment centre, which shut down after the junta became largely unable to test for the disease, began offering vaccines for the elderly on March 16. But after just 300 people showed up to the Inya Centre in Yangon’s Mayangone Township that first day – and after word spread on Facebook that anyone could be vaccinated there – the centre began offering the jabs to anyone aged 18 and older, a volunteer there told Frontier.

The programme is being managed by the Yangon Region Health Department and the Myanmar Red Cross Society, with help from other volunteer organisations. Officials at the Inya Centre would not speak to reporters, nor allow them to enter or to take photographs. But, posing on March 31 as willing recipients, Frontier reporters were able to go inside and speak to several volunteers.

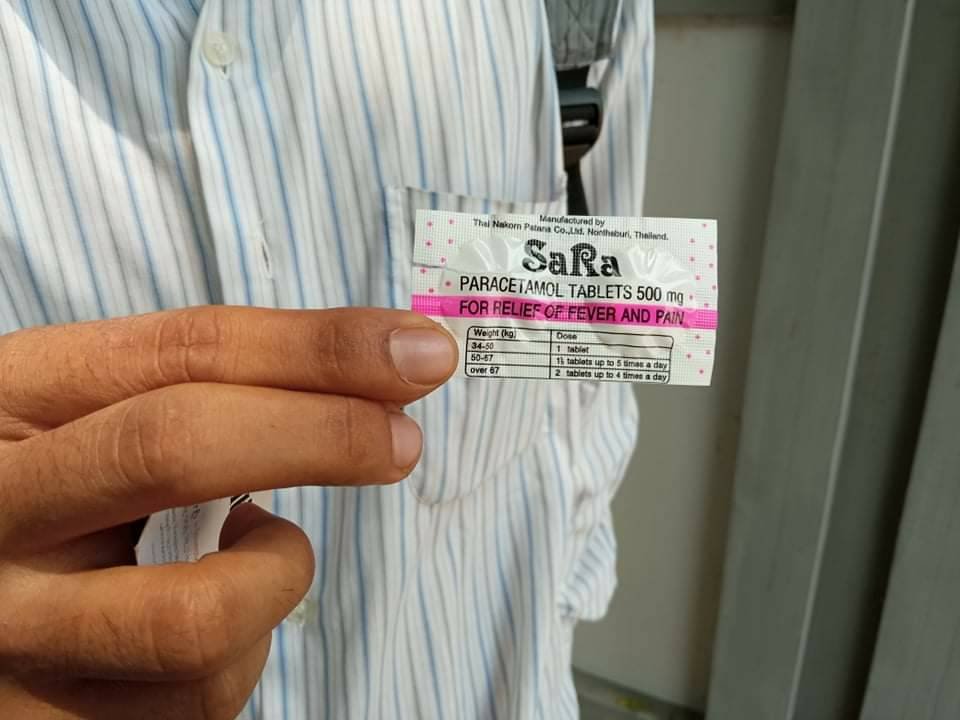

The centre is open daily from 9am to 4pm. Before entering, security guards take patients’ temperature and make them wash their hands with sanitary gel. They are then given a token with a queue number; when Frontier visited, two reporters had to wait just three minutes. The patient is called to a counter to fill out health and identity questionnaires, after which they are given a vaccination card and, finally, the jab. They are then offered 500mg of paracetamol and told to wait 30 minutes to ensure they have no negative reactions.

There was ample room to socially distance and the whole process took Frontier about 45 minutes, but the facility was below capacity. If demand were greater, longer wait times and more crowded conditions are not hard to imagine.

First doses of a COVID-19 vaccine are distributed at the Inya Centre in Yangon’s Mayangone Township on March 31. (Frontier)

One volunteer Frontier spoke to estimated that more than 15,000 people received their initial shot at the centre in the latter half of March, and that that day about 1,400 had come – what the volunteer said was about the daily average. They said most participants have been under the age of 65, with about half of them between the ages of 18 and 40 and 30 percent between the ages of 40 and 65. That leaves just 20pc in the over-65 cohort that the NLD had prioritised.

Among the vaccine recipients on March 31, Frontier saw Buddhist monks and nuns and factory workers of all ages.

“I got vaccinated because I do not want to ever suffer the horrors of quarantine,” Daw Cho Cho, 76, a retired public servant, told Frontier. “Now I can go to other states and regions if I show my vaccination card. Plus, it’s just good to be protected against COVID-19. No one can say when the coronavirus will disappear from the world.”

Cho Cho, who lives in Yankin Township, said she went to a high school in the township on March 25 hoping to get the shot but health officials there told her they’d run out. The officials also told her they’d been vaccinating not just the elderly but anyone aged 18 and over. She came to the Inya Centre when a friend of hers who lives in Mayangone Township told her about it.

The Inya Centre was first set up as a COVID-19 treatment centre on October 10 last year. A public health official who requested anonymity said running vaccination programmes at former treatment centres like Inya, which can perform thousands of jabs a day, is more effective than administering jabs at township-level outlets, such as local schools and health departments.

“If health authorities can do that, they can vaccinate more people more quickly. The more quickly we can get large numbers of people vaccinated, the safer we’ll be,” he said.

But this centralised approach is not universally preferred. In countries with more resources, vaccines are being rolled out to as many local outlets as possible, including private practices and pharmacies. The idea is to make getting the shot as easy and convenient as possible, and to avoid large gatherings of thousands of people, which could risk spreading the virus.

Private sector ‘ready’

Dr Myint Htwe, the ousted health minister in the NLD government, said at a COVAX National Coordinating Committee on November 25 that the ministry had planned to allow private hospitals and clinics to also offer vaccinations. At the time, however, few vaccines had been approved or recognised by the World Health Organization.

On February 24, the Food and Drug Administration, which operates under the health ministry, sent a letter to the Myanmar Pharmaceutical and Medical Equipment Entrepreneurs’ Association saying that anyone interested in importing COVID-19 vaccines could apply with the department to do so.

However, the FDA has not approved the use of the Covishield vaccine at private hospitals because the junta worries that if private facilities start offering it, rumours of corruption will spread that health ministry officials are illegally selling doses to the private sector, Khin Khin Gyi told Frontier. The agency has instead approved the Indian-made Covaxin vaccine and the Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines made in China for use at private hospitals.

Dr Htin Paw, president of the Myanmar Private Hospitals’ Association, told Frontier on March 20 that so far no pharmaceutical companies have imported vaccines but about three have offered to distribute them to private hospitals if licensed by the FDA to do so. However, it is unclear if any groups have taken up the FDA’s offer and applied to import any of the approved vaccines. Dr Theingi Zin, the junta’s FDA director, declined to comment.

“It is important that we, as private hospitals, provide vaccines that are legally imported and made available to the public at reasonable prices. The sooner people get vaccinated, the safer we’ll all be,” Htin Paw said. “The private healthcare sector is ready to do this.”

Of the 59 hospitals in Yangon Region with the cold chain storage technology needed to safely keep COVID-19 vaccines, 30 are privately owned and run, according to the MPHA.

Meanwhile, the available numbers for nationwide vaccination suggest a programme that is wildly off course, even if the current stock of vaccines are used before they expire.

By February 5, just 0.7pc of the Myanmar population – about 380,000 people – had got their first vaccine shot, according to data compiled by the Financial Times. By March 20, according to Khin Khin Gyi, that number had inched up to just 500,000, still less than 1pc of citizens. On the 8pm news on March 31, however, the military-run Myawaddy TV announced that more than 1 million people had received their first dose, and another 40,000 had received their second.

Khin Khin Gyi said the government does not have figures on the demographic breakdown of recipients, nor on the military-civilian split.

Before the coup, the elected government had targeted vaccinating 40pc of the population – some 24 million people – by the end of the year, with the remaining population expected to be vaccinated by 2023. Now, even these modest goals seem like a longshot. Still, the junta has no plans to rethink its approach.

“The current immunisation plan is the same as the previous government’s plan,” junta spokesperson Brigadier-General Zaw Min Tun said at a press conference on March 23. But carrying out the NLD’s plans seems to be impossible when you’re not the NLD, and the junta is unlikely to win the people’s trust before their vaccine doses expire – whenever that might be.