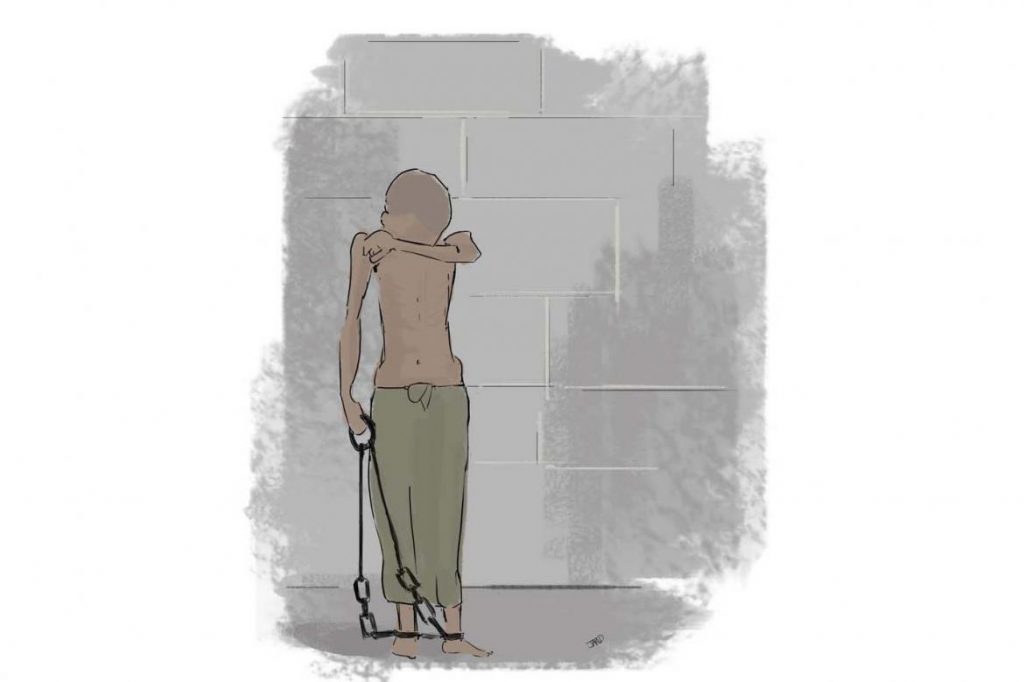

Myanmar under military rule was synonymous with political prisoners.

WHILE THE country’s best known prisoner of conscience was Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, who spent some 15 years under house arrest, advocacy group Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (Burma), estimates that there have been about 10,000 prisoners of conscience in the country’s jails since U Ne Win launched his military coup in 1962. Of that figure, AAPP estimates that about 240 have died while in jail or during interrogation.

Although there have been many amnesties since the quasi-civilian government led by U Thein Sein took power in 2011, there are still political prisoners in Myanmar’s jails.

As the 30th anniversary of the nationwide anti-government uprising known as 8-8-88 approaches in August, little has been done for the thousands of people who have suffered inside the country’s jails, which are renowned for their poor hygiene and the poor treatment of prisoners.

Days after her National League for Democracy party swept to victory in the 2015 general election, Aung San Suu Kyi was asked by reporters how she would deal with the country’s dark past. She replied that her administration would not be “going in for a series of Nuremberg trials,” a reference to hearings held after the Second World War to bring Nazi war criminals to justice.

Those who support this stance argue that Myanmar should look towards the future. They say that seeking justice for events that took place when the country was under military rule would not only re-open old wounds, but could also damage an already volatile relationship between the NLD and the military.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

But the government could be doing more. The NLD was formed out of the country’s democracy movement, and many of its members have spent many years in jail. As a result, there are some figures within the party who — Frontier understands — are keen to give the issue more attention, but such is the make-up of the party’s leadership, they appear to have little say.

The NLD administration has a great deal of challenges to overcome, and there are those who argue that issues such as the fledgling economy, the peace process and the crisis in Rakhine State are more important than dealing with what happened when the country was under military rule. However, how Myanmar deals with that past is important in charting its future.

Globally, there is a growing acceptance to talk more openly about mental health. Political prisoners, many of whom were subjected to torture, and spent months and years away from their families, have suffered more than most. Years after their release, many former political prisoners continue to struggle with issues brought about from their incarceration.

This is an area where the government can make progress. Health expenditure has increased in recent years, but remains low, especially when compared to spending on areas such as defense. The health budget must be increased further still.

With a shortage of government support, it has been left to mainly smaller organisations to work with former political prisoners, and their work includes programmes that prioritise their mental health, and help them to find jobs. The government should support these organisations, and could roll out more of its own.

There are larger victories that can be achieved too. One of the most important is to ensure that Myanmar has no more political prisoners in its jails, something that can be achieved through significant judicial reform.

The issues in Myanmar’s judiciary have been well publicised, in these pages and others. They include corruption, a lack of independence, and lawyers and judges who are poorly trained.

If Myanmar wants to view itself as a truly democratic country, it must ensure that there are no more prisoners of conscience in its jails.