Amid a harsh present, State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is asking voters to reflect on the past. Her own party’s past, to be exact.

Through a newly created Facebook page, Chair NLD, she has broadcast a series of lectures about the NLD’s long struggle against military rule.

It’s a story of hardship and sacrifice that political novices don’t fully appreciate, she implied. “Some of the newcomers do not understand how difficult it was in the past to be involved in politics,” she said in the second of the videos, uploaded on August 13.

Her words seemed to be a response to some of the disappointment at the NLD’s record in government. Watching her lectures, you sense that the party’s biggest adversary in the November election is not a rejuvenated military opposition or a consolidated ethnic bloc, but despondency over the prospects for a better society.

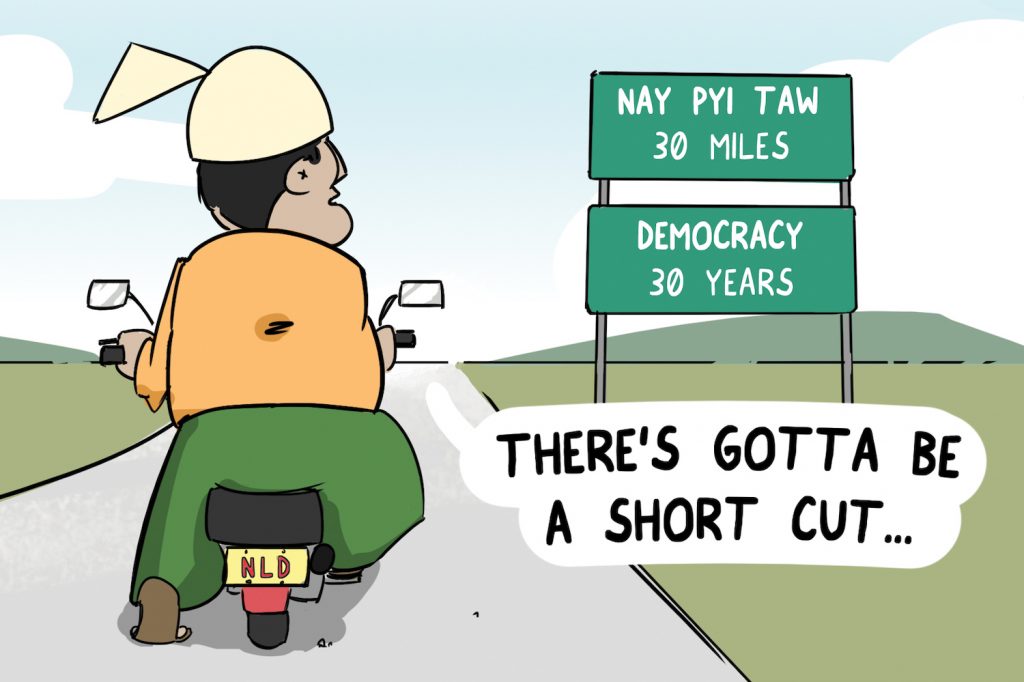

Much of this despondency, at least among the more politically engaged, is rooted in an attitude towards the 2008 Constitution. The military-drafted charter is often viewed as a dead weight obstructing all avenues towards democracy and peace. Not only are its rules stifling, but any effort to change it in a positive direction would be in vain because of the veto it hands to military appointees in parliament, the thinking goes.

While it’s important to be realistic about the prospects for change, this attitude can be its own kind of straitjacket. A truly democratic and peaceful Myanmar is indeed impossible under the constitution in its current form, but saying politics is at a dead end is convenient for those who want to keep the perks of office while avoiding the hard slog of reform.

First, consider vital reforms that could be undertaken without changing a single letter of the constitution.

The civilian government has a full mandate to reform the judiciary. State prosecutors are under the attorney general, who is a presidential appointee, and courts are administered by the Supreme Court, whose justices are also appointed by the president. The NLD has taken some baby steps towards fixing the courts. But as shown by the continued imprisonment of peaceful activists on spurious charges – not to mention the countless legal injustices that take place every day, and go unreported – there is much to be done.

But what of that other key component of criminal justice, the police? The force is part of the Ministry of Home Affairs and is therefore under Tatmadaw command, but it’s questionable whether the constitution requires this.

Section 338 says “all the armed forces in the Union shall be under the command of the Defence Services”. The “armed forces” in most countries refers to the army, navy and air force. Whether the term includes the police in Myanmar is perhaps a matter for the Constitutional Tribunal to decide, but it’s worth remembering that the General Administration Department (which also has a security mandate) was considered essential to the military’s continued control of society – right up to the point when the government announced it would move from home affairs to a civilian-controlled ministry in late 2018.

Next, consider constitutional changes with far-reaching benefits that the Tatmadaw would not veto, and might even support. Exhibit A is a proposed change to Article 261 that would allow the chief ministers of the states and regions to be elected by regional assemblies, rather than being appointed by the president.

By forging a more direct link between voters and their regional governments, and providing a space for ethnic parties, this reform would be a concrete step towards the federal union the NLD claims to be working towards. It also has the support of military-aligned MPs, but the NLD voted down a related amendment bill in parliament in March out of what looked like political self-interest: Under the current distribution of seats in regional assemblies, the NLD would lose two subnational governments, Shan and Rakhine. After November 8, it may find itself in a minority in even more of the ethnic states.

These examples suggest that the failure to deliver change has less to do with the constitution and more to do with political will and capacity. The NLD showed courage in drafting constitutional amendments which, as expected, were voted down by military MPs early this year. Let’s hope the next government marries this courage with a more pragmatic plan of action.

This editorial will appear in the August 27 edition of Frontier.