A lucrative hybrid seed trade is sprouting in Myanmar, thanks to a growing farm sector and relaxed visa regulations.

By PETER JANSSEN | FRONTIER

Alex Bookbinder / Frontier

The devastating floods in July and August weren’t bad news for everybody.

“It was an opportunity, too, because it means farmers need to buy more seeds since whatever they had planted is gone,” said Kittitouch Pattanakittipong, the manager in Myanmar of East-West Seed International Ltd. In the aftermath of the floods, East-West distributed free vegetable seeds to hard-hit farmers, in a move that combined charity and marketing. “When they learn they are good, they will come back and buy them,” Mr Kittitouch said.

East-West’s sales were below the company’s targets in July and August, but exceeded them by 120 per cent in September and October, said Mr Kittitouch. East-West expects yearly sales to reach US$5 million (about K6.38 billion), up sharply from US$3 million last year.

The Netherlands-based company has been a market leader in the hybrid vegetable seeds industry in Southeast Asia for more than 30 years, and sees huge growth potential in Myanmar because of its largely agriculture-based economy.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Perhaps one of the greatest unsung benefits of the reform process started by President U Thein Sein in 2011 was a relaxation on visas for foreign experts. For East-West, which depends greatly on extension programs in rural areas to help sell its seeds to farmers, the visa relaxation was a breakthrough. “What has changed is the operation itself,” Mr Kittitouch said. “We can bring in more foreign expatriates. And four, five years ago if you were a foreigner you couldn’t travel around the country without getting permission from the local government. Now it’s different.”

Simon Groot, a Dutch national whose family business had been producing hybrid seeds for the European market, established East-West in the Philippines in 1982. Over the past 33 years, the company has expanded its hybrid vegetable seed business to Thailand, Indonesia and Vietnam, as well as to India and China. Technological expertise has helped East-West to become a market leader. “The seed business is very unique,” Mr Kittitouch said. “Even if you have a lot of money, you can’t catch up with the old players in one or two years because you have to have the good R&D and germplasm.”

East-West’s main rival in Southeast Asia has been traditionally been the Chia Tai Group, an affiliate of Charoen Pokphand Group, Thailand’s largest agricultural conglomerate. Since opening an office in Yangon nine years ago, East-West has gradually replaced Chia Tai as the main seed provider in Myanmar, say industry sources, although verification is difficult because of a paucity of sales data. “The reputation of East-West, or their Sorn Daeng – Red Arrow brand – is very good in Myanmar,” said Niran Nirannot, who was formerly with the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation in Myanmar and is working for the United Nations Development Program in Bangkok. “I don’t doubt their claim to expect five million dollars in sales for 2015,” she said.

East-West’s marketing campaign in Myanmar began informally. Myanmar buyers bought seeds directly from East-West’s Thai headquarters at Nonthaburi, just outside Bangkok, or they were imported from the company’s operation in the northern city of Chiang Mai. When the Myanmar market got big enough, East-West opened an office in Yangon. It was only after visa restrictions were relaxed in 2011 that the company could bring in the technical staff it needed to train the extension teams that play a crucial role in sales, because most farmers are poor and understandably reluctant to spend money on seeds.

Alex Bookbinder / Frontier

“Four, five years ago if you were a foreigner you couldn’t travel around the country without getting permission from the local government. Now it’s different.”

Myanmar farmers have traditionally relied on natural, open-pollinated seeds, but most commercial-scale seeds are F1 hybrids, which are infertile and have to be bought each season.

“They think the seeds are very expensive,” said U Thein Tun, an East-West extension team leader. “But if it is profitable, they don’t complain.” Typically it takes an extension team two to three years to convince a farming community that it is worth investing in hybrid seeds. East-West’s preferred marketing strategy is to choose a competent farmer and provide him or her with the other ingredients for success, which include fertiliser, pesticides and know-how. These gifts demonstrate the benefits of modern technology to other members of the community. “Seeing is believing,” U Thein Tun said.

Hybrid seeds are expensive, although they typically account for less than 10 percent of a farmer’s total investment costs. For example, the total investment needed to grow an acre of watermelons is between $500 and $700, with the hybrid seeds costing $50 to $70. That’s not cheap, but it’s a necessary investment for farmers eyeing export market opportunities. “The price of seeds is quite high, but if they don’t use F1 hybrid seeds they cannot export, because of quality issues,” U Thein Tun said. Watermelons, grown mainly in Mandalay Region, have become a cash crop for export to the Chinese market, where they cannot be grown during the winter months from November to May. Hybrids are to be distinguished from genetically modified organisms (GMOs), which East-West insists it never deals in.

Chilli peppers are also emerging as an export crop, with most sent to China. The main growing area is around Nay Pyi Taw and the chillis are dried for the export market. Hybrid seeds ensure such qualities as strong colour, good taste and long shelf life, all important factors in Myanmar because of its poor transport infrastructure, which adds to the cost of all inputs, including seeds.

“We truck seeds from Bangkok to Mae Sot for 50 Baht (about Kyat 1,800) per carton (about 20 kilograms), and from Mae Sot to Yangon for another 300 Baht (about K10,700),” said Chatchai Rithichai, marketing manager for Thai Seed & Agriculture Co., Ltd, to illustrate the effect of transport infrastructure on costs.

Transport is not the only constraint in the market. One reason East-West’s sales are on an upswing this year is because it has expanded its upcountry sales team. It had previously relied on four or five dealerships based in Yangon but this year has opened sub-dealerships throughout the country. More sales in upcountry markets, however, has meant more problems.

“Myanmar is a cash-based economy, but East-West doesn’t allow the sales teams to carry cash,” Mr Kittitouch said. In most countries, East-West asks farmers to make payments through the banking system, but in Myanmar that can take time. “Some of our customers have to travel two to three hours to get to their nearest communal bank, that’s why we have to allow them to make payments a week after shipment,” he said. In Thailand, most farmers make payments on their mobile phone apps, but in Myanmar farmers either lack access to the internet, or connections are unstable.

East-West’s biggest markets are around the country’s main urban centres – Yangon, Mandalay, Bago and Nay Pyi Taw, as well as the Ayeyarwady Delta – but its best-known success story for hybrid seeds is Inle Lake in Shan State.

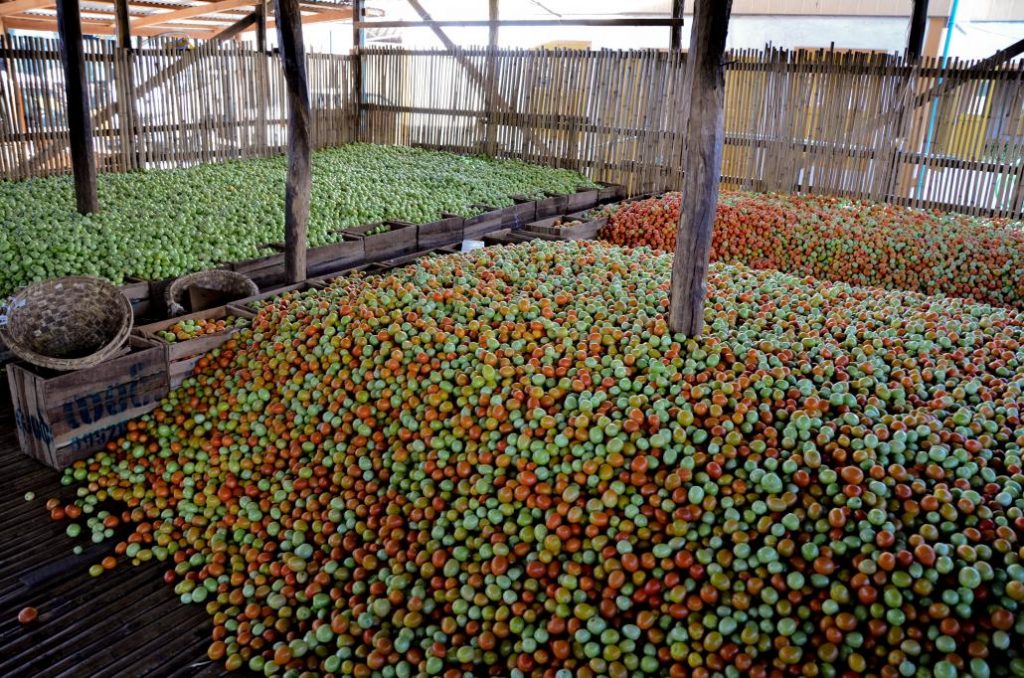

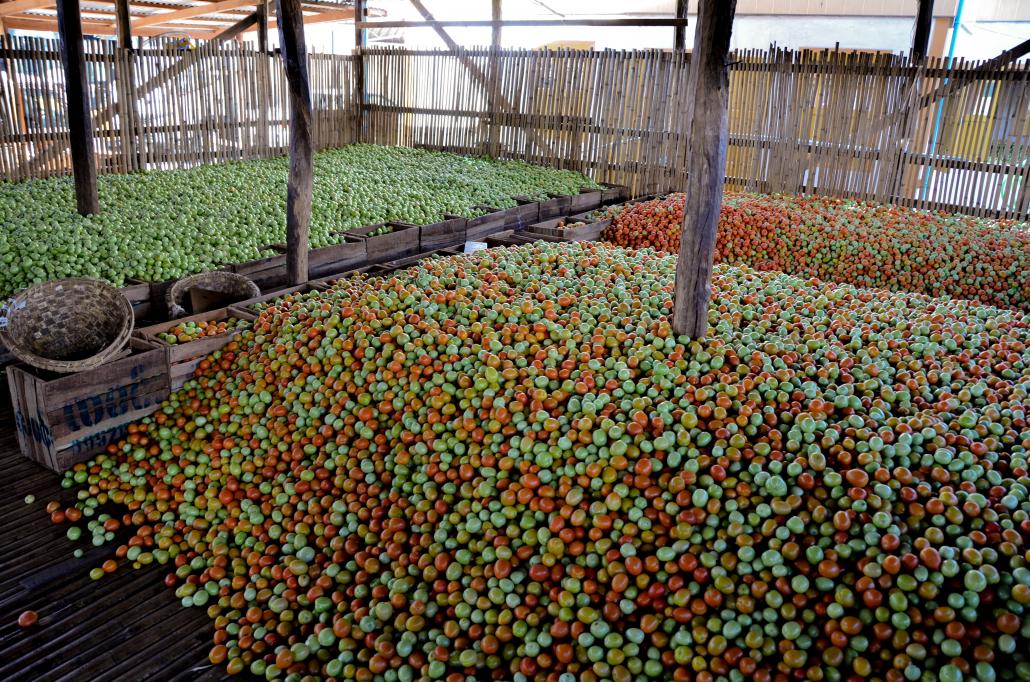

For several years, hydroponically-grown tomatoes have been a big money earner for farmers living around the lake, but that might not have happened without hybrid seeds.

“There are more than 20 companies selling tomato seeds there. Chia Tai alone is selling 15 different varieties,” Mr Kittitouch said. East-West prefers to concentrate on one of two varieties that meet the farmers’ specific needs. “We concentrate on transportablilty there. The Shan State is sending tomatoes to Mandalay and everywhere in Myanmar, but the roads suck.”