Positive developments in Myanmar over the last year have been tempered by new challenges, tragedies and upheaval.

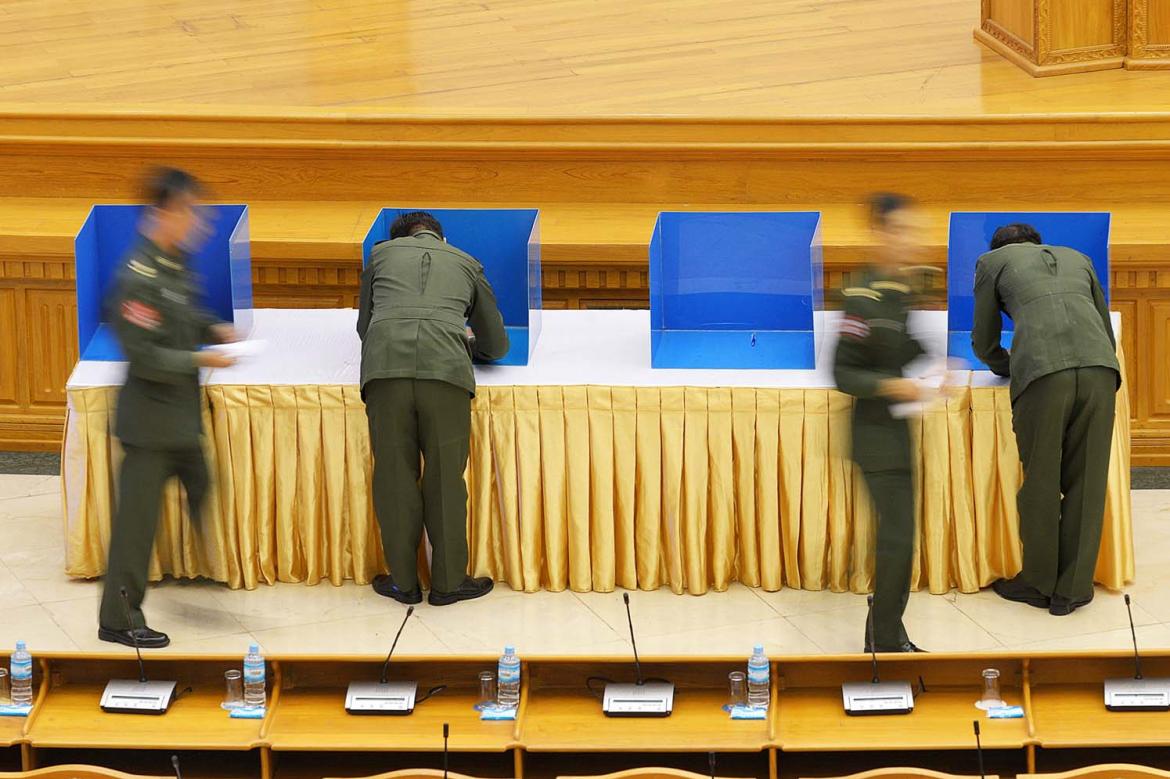

For anyone living and working in Myanmar, or watching it closely from afar, 2015 has been an exciting year. Although the momentum of the reform process seemed to wane during the year, it ended with the nation poised for a new era of change after the National League for Democracy’s stunning election victory on November 8. Developments since then have raised the people’s hopes that the military is prepared to accept the transfer power to a democratic opposition, unlike in 1990.

Of course, there are many shades of grey. It remains to be seen how democratic the democrats will be. The NLD seems to be a personal vehicle of its leader, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, the party’s decision to exclude Muslim election candidates has an uneasy feel to it and its MPs and MPs-elect are not allowed to discuss policy matters. Meanwhile, the army enjoys privileges that guarantee its grip on large parts of the government apparatus. Against that background it will be a challenge for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to deliver on the huge weight of expectation created by her party’s victory.

The year that was, was also a year of tragedies and upheaval. Floods affected much of the country and disrupted the lives and livelihoods of more than a million people and the Kokang conflict that erupted in February claimed scores of lives and displaced thousands.

The signing of a national ceasefire agreement in October was a positive development and although in itself a testament of the growing trust between the Tatmadaw and some armed ethnic groups, was not the milestone it has been touted to be.

The continued fighting in Shan State, and the fact that many armed ethnic groups did not sign the NCA and will not participate in the political dialogue due to begin in January, show that much work is left to be done in the new year to move the peace process forward.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

For some in Myanmar, misery in 2015 was nothing new, but simply a continuation of hardship already endured. Threatened livelihoods and repression led to an exodus of Rohingya Muslims and the ‘boat people’ crisis in May and June. The whole world saw Myanmar’s internal problems spill over into the region.

The adoption by parliament of the four race and religion laws drafted by the ultranationalist monk-led Ma Ba Tha group, the rejection by most political parties of Muslims as election candidates and the disqualification of many Muslim candidates by the Union Election Commission provided further evidence during the past year of rising intolerance in Myanmar.

But on the whole a positive feeling prevails. The transition, a process comprised of thousands of smaller vectors, is moving forward. The roadmap for the transition unveiled by the military more than a decade ago still determines how the country is governed and how its economic assets are owned and monetised, but has paved the way for significant reforms, including a freer press, the emergence of civil society organisations, the right to form trade unions and the country’s first minimum daily wage.

Many challenges remain. We will soon know if the new government has the capacity to meet them, in a year that promises to be no less crucial than the previous twelve months.

For us, the owners, reporters, editors, marketing team, layout artists and distributors of Frontier, 2015 was the year in which it all started. Our journey began on July 2, when our first issue hit the newsstands. Six months and 26 issues have passed. We have learned that as well as a rich lode of stories waiting to be mined in transitional Myanmar, there is also an audience keen to read them, and understand this remarkable country on the crossroads of India, China and mainland Southeast Asia a little better.