A new cycling tour that follows that travelled by one of Myanmar’s best-known kings in the 16th century aims to create more jobs in the tourism industry, and showcase the country’s greatest asset: its people.

By THOMAS KEAN | FRONTIER

Photos NYEIN SU WAI KYAW SOE

YANGON CAN sometimes feel suffocating, with its city limits an artificial, yet too-rarely surmounted, barrier to the rest of the country.

After living in Yangon for a while, you will most likely have dragged yourself to Bago and Thanlyin, and probably Twante, Hlawga or Pantanaw. You may even have tried to find a beach at Letkokkon and discovered only a muddy, mangrove-lined foreshore.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

And then once you’ve done that, you’ll have gazed wistfully at a map of the country, noting that most of Myanmar’s attractions and activities are hundreds of kilometres away – too far for a day trip and even a weekend getaway.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

But it doesn’t have to be like this; the journey can be the point. And the seemingly most mundane village setting can be more interesting than the grandest pagoda.

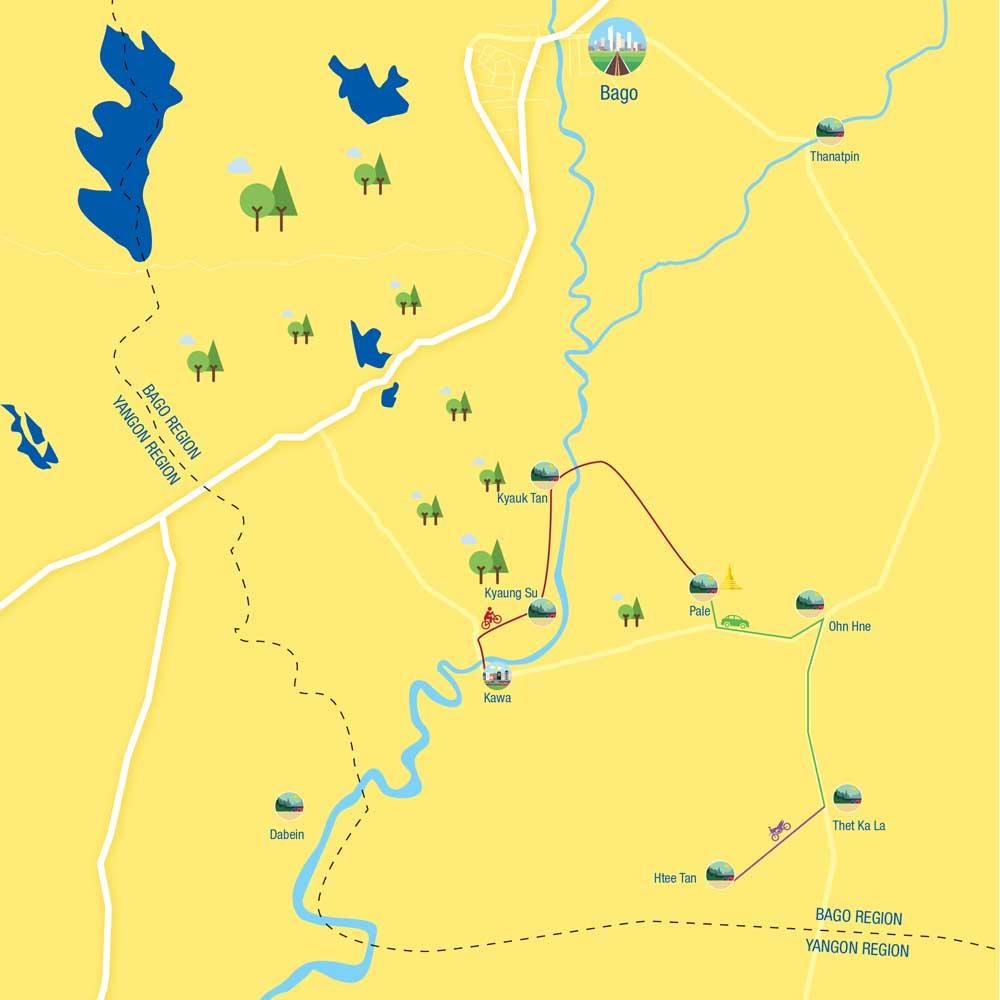

At least, that’s the philosophy that underpins Village Life on the Old Dhammazedi Road, a bicycle tour offered by Khiri Travels that showcases rural communities south of Bago.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

In 2015, the tour was among several to win grants from the Business Innovation Facility through its Product & Package Innovation Competition, an award programme designed to encourage inclusive tourism.

The name of the tour is a reference to King Dhammazedi, the most famous monarch of the Hanthawaddy Empire that once ruled much of lower Myanmar from its capital at Bago.

When the king travelled to Yangon – then known as Dagon – to pay homage at Shwedagon Pagoda, he would travel not along the modern highway but directly south from Bago and down through eastern Yangon Region.

typeof=

The tour begins in Kawa, reached by turning off the Yangon-Bago Highway at Intagaw. There are no big-name sites here: just 30 kilometres of quiet country roads, fast-flowing delta waterways, and unheralded stupas and monasteries.

Along the way, visitors can stop at local stores selling handicrafts and produce, including one shop renowned for its jam. In Kyaung Su, we took a break to chat with women making sheets of dani thatch for use as roofing. The sheets are made by folding the leaves over a frame and snapping off the hard stem to make a needle that secures the loop.

While some residents were making the thatch outside their homes, many were employed in a workshop owned by the village administrator, who welcomed us in for a cup of green tea.

Daw Ka Yee, left, makes dani thatch beside her home in Kyaung Su village. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

About 30 women sat on the ground amid towering piles of dani harvested in the Ayeyarwady delta and sent to Kyaung Su by boat. The thatch sheets are made during the dry season, from December to April, when there is little cultivation, and are mostly used by farmers as roofing on temporary huts out in the fields. The women in the workshop were clearly experienced; their hands moved in a blur of motion. The fastest can make up to 500 or 600 sheets a day, earning K1,000 for 100 pieces.

Shortly after leaving Kyaung Su, we crossed the Bago River along a narrow suspension bridge at Kyauktan. At the bridgehead on the other side we stopped to catch our breath, and an abandoned object beside the path caught my eye: a sugarcane grinder used to make juice, but with an unusually large wheel on the side, almost novelty sized. As I pointed this out to our guide, an elderly woman sitting in a hut nearby offered to sell it to me for K200,000.

Women at work inside a small factory run by the village administrator. (Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier)

When I asked how she expected me to move such a heavy piece of machinery in a village with no road access, she pointed to a bullock cart that was slowly pulling away from us down a dirt road: It was packed with belongings and children, and was clearly being used to shift home. We raced the cart to the edge of the village, marked by towering tamarind trees that must have been several decades old, if not more.

From here it was a long, slightly undulating stretch toward Kyaikmakaw Pagoda in the searing March heat. At one point, we paid a small toll to cross a bamboo bridge, about 50 metres long, that is built each year at the end of the rainy season and dismantled when the rains return. Outside the pagoda – said to contain a hair of the Buddha donated by a merchant from the ancient Mon kingdom of Thaton – we dropped gratefully into a teashop and savoured a delicious sugarcane juice packed with plenty of ice.

Once we had cooled down, we drove east to the Bago-Thongwa-Yangon Road and proceeded south, stopping at Thaketla village. As we got out of the car at Thaketla, I realised that I had been here before: in May 2010, while covering a story about water shortages during the El Niño year.

At the time I had been shocked by the deprivation, but there were signs of improvement, including a new water channel, a large monastic school and a dry season road that hadn’t been there on my previous visit.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

We took a motorbike across dusty fields to Htee Dan, a farming village that’s not even close to the main road, let alone the tourist trail. A home-style lunch was waiting for us; after the exertions of the morning, we made short work of it.

Htee Tan is the home village of Ko Zaw Min Oo, who created the tour together with Mr Edwin Briels, the managing director of Khiri. Zaw Min Oo joined the company in 2012, shortly after returning from Singapore. He had worked in tourism before, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but at Khiri discovered a passion for creating tours that showcase little known areas of the country and generate new sources of income for residents.

Htee Tan fit the bill well. Although not particularly remote, it still has no government-supplied electricity – some residents have solar panels – and the only water source is the village pond (Khiri has since dug a well to provide an emergency supply in summer, and also built a bridge to connect the two halves of the village during rainy season).

It still has no middle or high school; Zaw Min Oo recalled that he was one of only two people in the village who finished high school in nearby Thakala. Most dropped out at the primary level.

“I wanted people from this region to get more jobs and also be in touch with foreigners,” Zaw Min Oo told Frontier recently.

Zaw Min Oo and Briels visited the area four times over a three-month period to design the tour, and also studied the history of the region.

“We started sending clients but we kept making adjustments. Originally we had planned to go there by train to the jam factory [in Kyauktan], but the train didn’t run every day.”

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

Briels said he hoped the success of tours like Village Life on the Old Dhammazedi Road would encourage other operators to focus on areas away from the big cities and showcase the country’s greatest asset: its people.

This will give tourists more reason to stay longer in Myanmar or make return visits, he said.

“The number of tourists worldwide that want to visit temples all day, every day is limited and in order to expand the tourist arrivals and expand the number of Myanmar people able to earn a liveable income from tourism we need more tourist attractions,” he said. “Innovative and engaging experiences for foreign tourists are crucial for the tourism industry.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Zaw Min Oo. Although he has left Khiri to take up the position of general manager of tour agency Peace House, he’s continued to design new programs, most recently launching a three-night trekking tour in Mon State.

“Every year we want to come out with new products, new creative tours, which are completely different from other companies. We try to make them action-packed, in touch with locals, using different types of transportation modes,” he said.

“There are more than 2000 travel companies in Myanmar, but you can count just a few that are successful. We need to consider what travellers actually want.”