The lavish spending of former naval commander U Soe Thane may keep Bawlakhe safe for the Union Solidarity and Development Party, and COVID-19 restrictions are making matters harder for competitors.

This article is part of Frontier’s Tale of Five Elections series. We’re following the election through five townships across the country, capturing events and local voices through the campaign, voting and declaration of winners. Scroll to the bottom for the first article on Bawlakhe.

By EI EI TOE LWIN | FRONTIER

Early in September, as official campaigning began, Kayah State found itself in an enviable position: it was the only state or region in Myanmar free of COVID-19 cases. Then, on October 15, the seemingly inevitable happened: Kayah announced its first case.

But the state was never exempt from guidelines set by the Union Election Commission for the campaign period, which ends on November 6, two days before the election. They limit rallies to no more than 50 people and include social distancing and other measures.

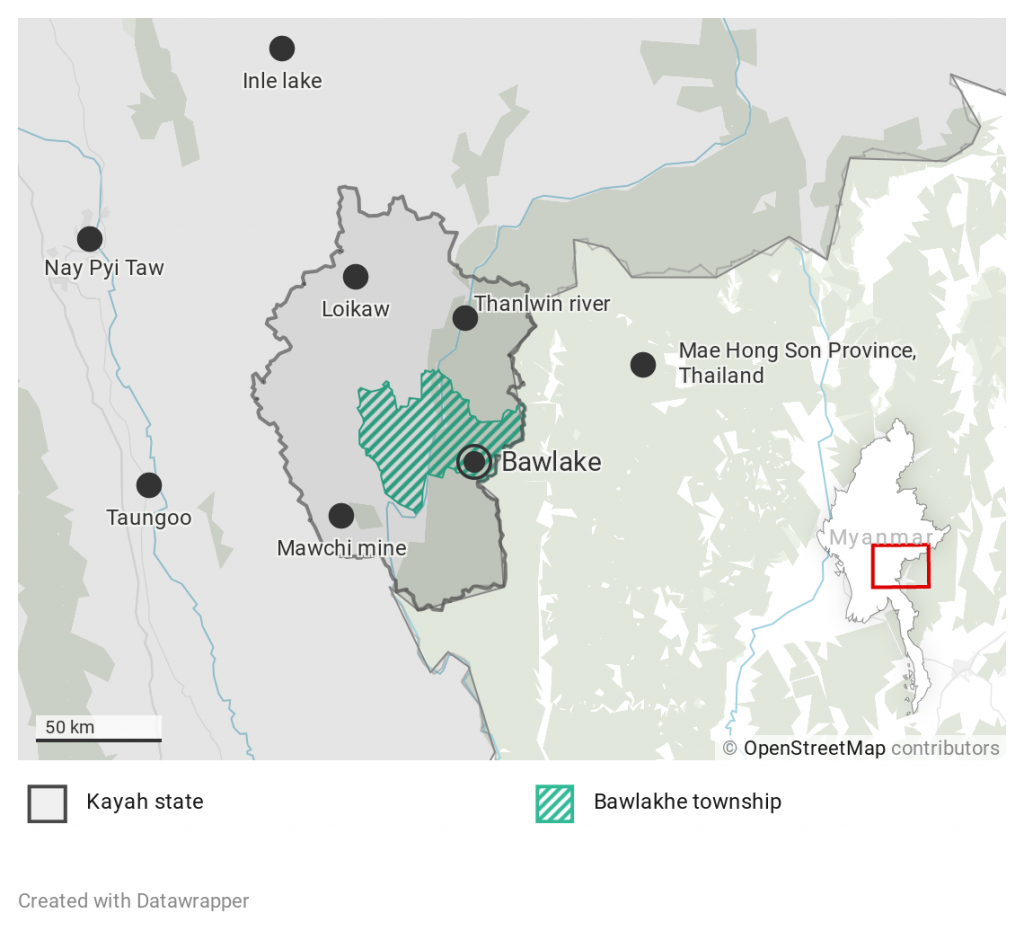

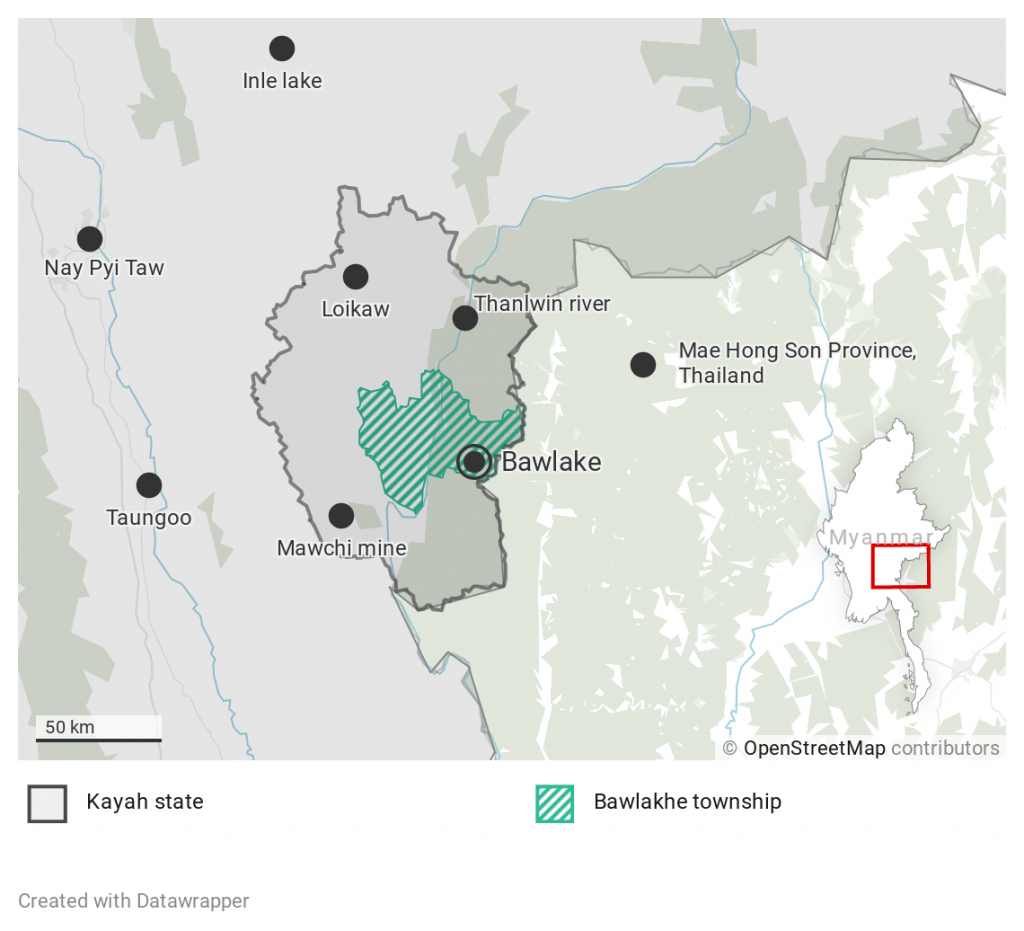

So Kayah’s lone COVID-19 case hasn’t changed much for candidates in Bawlakhe Township, where 40 from eight parties and one independent are vying for five open seats. Several told Frontier their strategies have consisted mostly of trying to engage voters by canvassing door-to-door while keeping a safe distance, and holding rallies of fewer than 50 people.

Union Solidarity and Development Party MP U Kyaw Than, who is seeking re-election to the Kayah-3 seat in the Amyotha Hluttaw, seems unconcerned.

“I don’t mind not being able to hold events with many people. My constituents know me well and I’ve explained to them what I’ve been doing in parliament for the past five years,” he said.

Bawlakhe is far from the only township in Myanmar where incumbents are more sanguine about the restrictions than their challengers. However, it is one of the few places where politics is dominated by a single politician who isn’t Daw Aung San Suu Kyi.

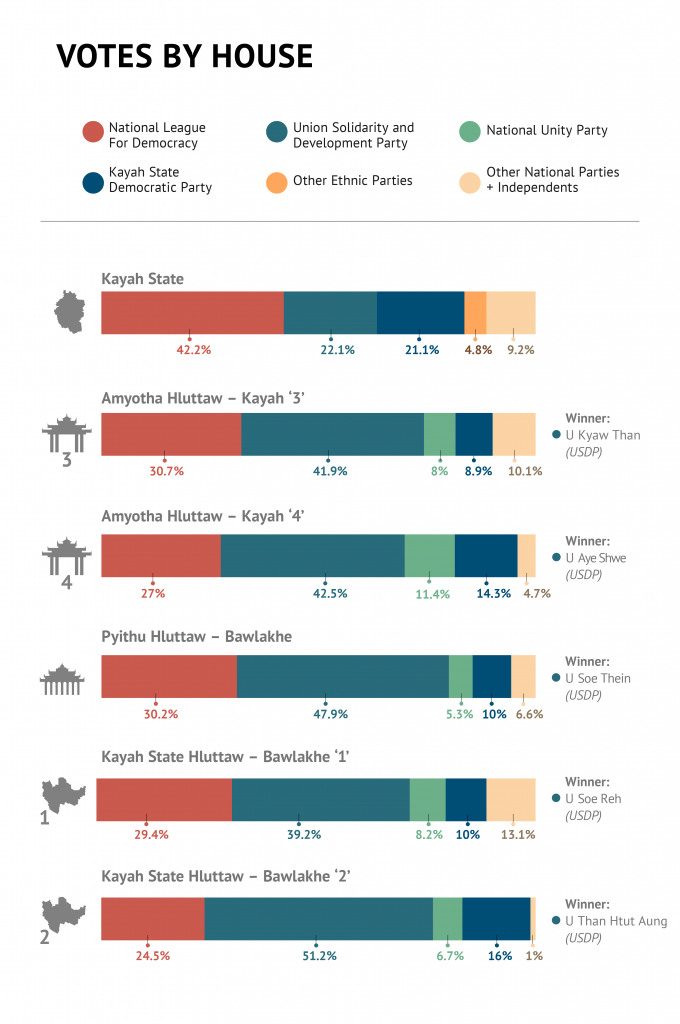

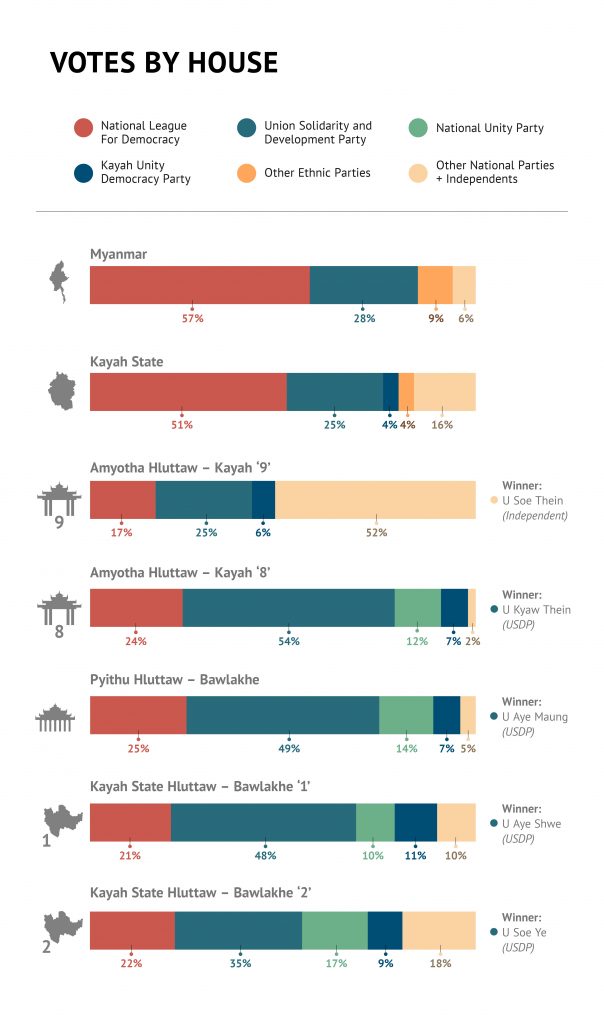

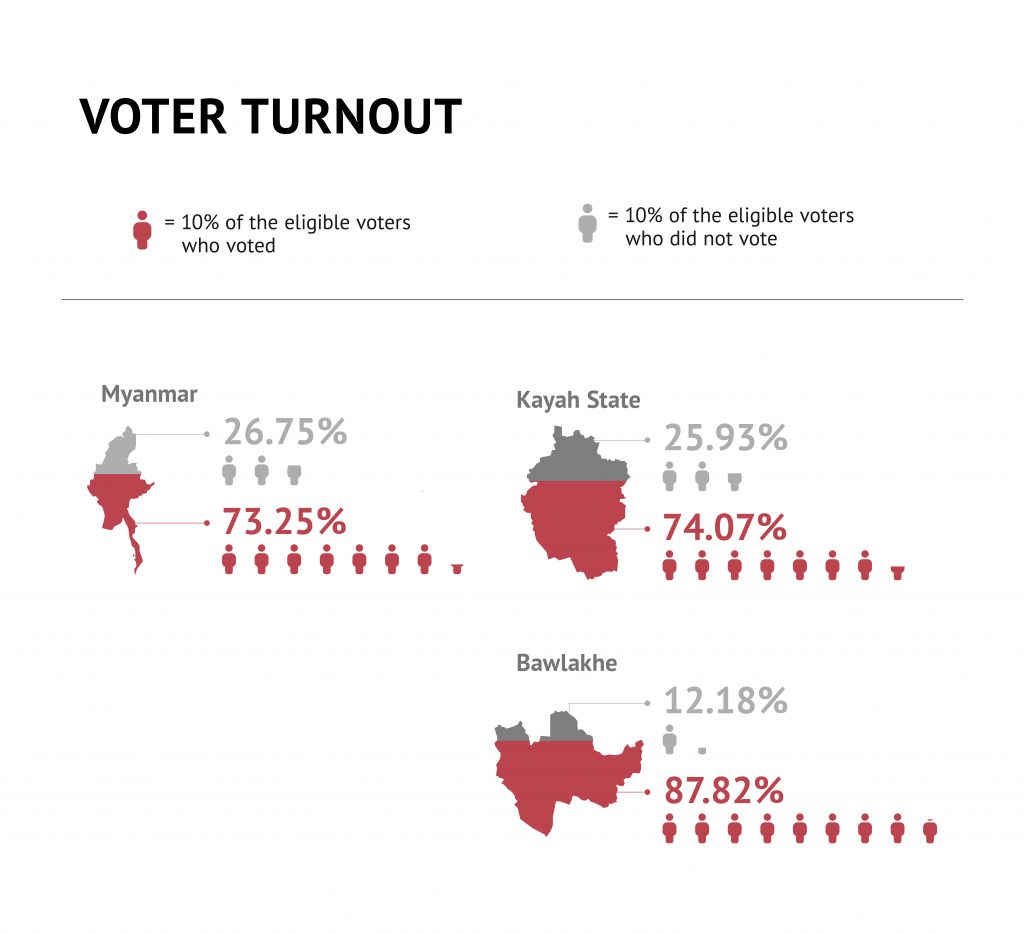

The township is a USDP stronghold. The military-backed party swept Bawlakhe’s seats in 2015, creating an island of green in a state that overwhelmingly turned red. Of the seven seats it won in the state, four – both state hluttaw seats and one seat each in the Pyithu Hluttaw and Amyotha Hluttaw – were in Bawlakhe.

The other Amyotha Hluttaw seat in Bawlakhe, Kayah-9, was won by an independent, U Soe Thane. The former Tatmadaw naval commander and president’s office minister was prevented from competing under the USDP banner by a factional squabble within the party. He has returned to the USDP this year to contest the Pyithu Hluttaw seat for Bawlakhe.

Known for his wealth – and for spending significant chunks of that wealth directly on voters – Soe Thane’s continued largesse makes for a David-and-Goliath-like competition with his main challenger, the NLD’s Sai Lin Lin Oo.

As Frontier previously reported, for many Bawlakhe residents, elections are a chance to cash in, and no one has quite as much cash to offer as Soe Thane. In May of this year he donated an ambulance worth more than K10 million to the Bawlakhe-based Forever Hands Social Welfare Association.

“We don’t care what seat he runs for, as long as he is running in Bawlakhe,” said U Zaw Zaw Oo, the association’s leader. He believes most of the association’s 3,200 members will vote for Soe Thane with him.

“Perhaps not all members, but I can guarantee that the votes of 720 permanent members will go to Soe Thane; this is the only way we can thank him for what he has done for us,” he told Frontier in August.

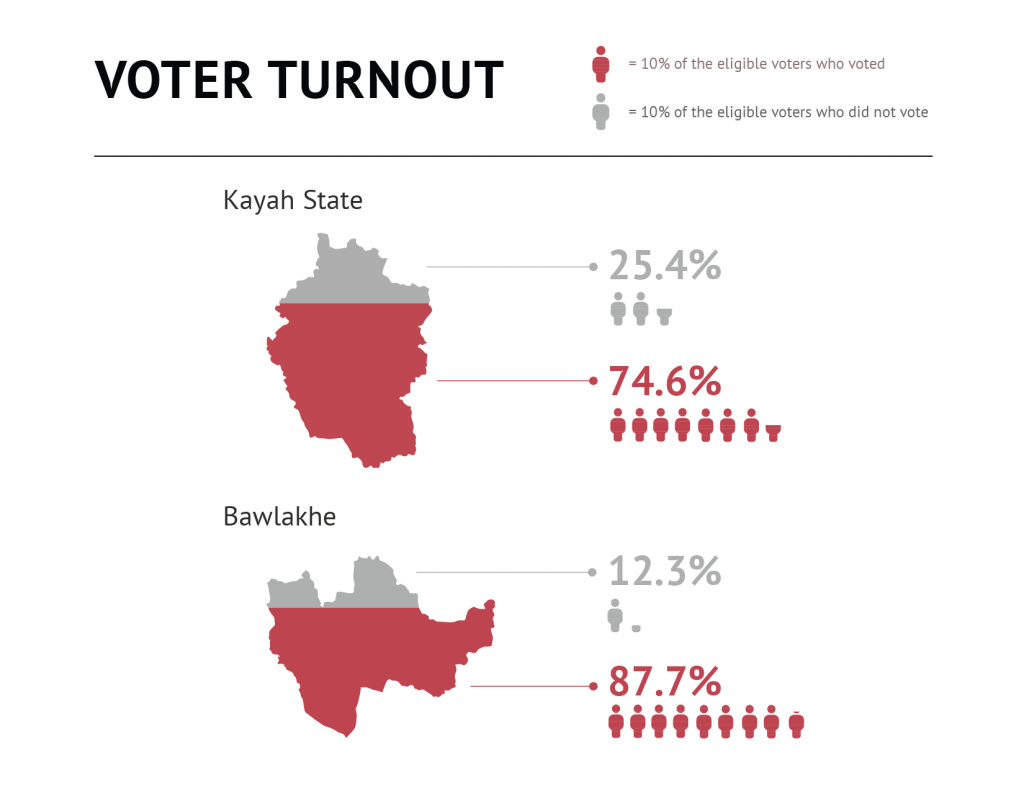

These votes will go a long way in a township with little more than 8,000 voters, and even NLD candidates acknowledge Soe Thane’s power.

“Speaking frankly, he could still maintain [the USDP’s] stronghold in Bawlakhe,” said Daw Mi Mi Maw, the NLD candidate for the state seat of Bawlakhe-1. His image as the township’s patron-in-chief was so firmly rooted in residents’ minds, she said, that “even if a bridge is built with government funds, they will call it the U Soe Thane bridge”.

Mi Mi Maw also feels disadvantaged by the COVID-19 restrictions.

“I really wanted to hold big events to shore up support, to flip Bawlakhe from a green to a red zone,” she said. “But I have to prioritise people’s health over winning an election.” Instead, she’s been holding small campaign events and canvassing door-to-door, but she said she doubts this will be as effective.

“In my experience, local people are very honest and very stubborn. It is very difficult to get them to change,” she told Frontier. “They assume that U Soe Thane has done many things for them and say they are in debt to him – that if they don’t vote for him they will be in debt to him for the rest of their lives.”

Mi Mi Maw had to get special approval from the NLD’s central executive committee to contest the November election for the party, after breaching a core NLD principle by standing for another party in a previous election.

In 2015 she stood for the state assembly’s Bawlakhe-2 seat as a Kayah Unity Democracy Party candidate but lost to the USDP candidate.

NLD township chair Sai Gyi believes the party lost all seats in 2015 partly because it chose non-residents as candidates.

“I don’t want to lose this time. To make sure we win as many seats as possible, I asked the party to accept Mi Mi Maw, a local resident, as a candidate,” he told Frontier. “Senior party officials accepted my request for the sake of the party.”

When Frontier travelled to Bawlakhe in July, most residents said they were yet to decide who to vote for, but there were already indications of a strong reservoir of support for Soe Thane.

Despite this, Sai Gyi says he’s confident the NLD will do better than it did in 2015, when the local authorities made it hard for him to field candidates and recruit party members, and the presence of three Tatmadaw battalions and a Tatmadaw-aligned Border Guard Force in the sparsely populated township made it dangerous to oppose the military-backed USDP.

“At the time, the authorities threatened to kill residents if they joined the NLD,” he said. “In military-dominated areas, people were seriously oppressed. I was stomped on with army boots and sent to jail very often.”

Those fears have gradually diminished under the NLD government, he said.

“There is more interest in joining the party. I now have more than 1,000 members. People have come to understand that, even though the USDP won locally, it couldn’t do anything without control of the central government. This year they know that they need to vote for candidates from the party that will form the government.”

Residents and local MPs say that, because of the NLD and USDP’s inability to work together, Bawlakhe has been “left behind” for the last five years.

“The [central] government doesn’t want to help us because its candidates lost here, and our USDP MPs can’t do much when the government ignores their requests,” said U Win Maung, a resident of the township’s Ywathit village. “No wonder we’ve been left behind and are still living in poverty.”

But NLD membership in Bawlakhe is still just half that of the USDP’s 2,000. With Soe Thane’s largesse and the township’s 1,200-plus military votes, the USDP may yet celebrate another landslide in November. “I would be very proud if the NLD won only three [out of five] seats in Bawlakhe,” said Sai Gyi.

U Aye Maung, the USDP township chairman and Pyithu Hluttaw MP, was confident his party could hold Bawlakhe. “We MPs have had some problems in the NLD-dominated parliament … but we did our best, and people know that,” he said. .

He’s standing aside this November to let Soe Thane contest his seat, he said, “because he can do a better job than me of representing the interests of the local people.”

Meanwhile, the Kayah State Democratic Party’s township chair, Saw Nee Ni, is gloomy about his party’s prospects in Bawlakhe. The party is a merger of two Kayah-based ethnic parties, the Kayah Unity Democracy Party and the All Nationalities Democracy Party, which both did poorly in 2015. The new party enjoys considerable momentum elsewhere in the state, partly thanks to the backing of ethnic civil society activists who supported the NLD in 2015, but it has only around 200 members in Bawlakhe and very little money.

“Although we’re contesting all seats [in the township], we don’t even have a party office or funds to support our candidates, who are campaigning with their own money,” he told Frontier. “We’re not sure it’ll work.”

While resurgent ethnic parties are poised to redraw the electoral map across much of Myanmar’s ethnic borderlands, in Bawlakhe, it seems, it’s better the devil you know.