Ethnic parties are battling larger, national ones by focusing on state-level issues in the Kachin State capital, but the pandemic has made it hard to reach rural, offline voters.

This article is part of Frontier’s Tale of Five Elections series. We’re following the election through five townships across the country, capturing events and local voices through the campaign, voting and declaration of winners. Scroll to the bottom for the first article on Myitkyina.

By PYAE SONE AUNG | FRONTIER

Restrictions on large gatherings to curb COVID-19 have made the election campaign period more subdued than in 2015, but in the Kachin State capital of Mytikyina, visual proof of the November election is everywhere. People wearing t-shirts and masks with different party logos throng through the streets and markets of the northern city on the Ayeyarwady River.

Party swag is one way candidates are trying to build name recognition while still adhering to health measures. Ze Lum, a campaign manager from the United Democratic Party, said the party has run out of t-shirts several times and has had to order more.

Unlike in 2015, candidates cannot hold public meetings at churches, monasteries or large community halls. Instead, they are exhausting themselves by traipsing door-to-door in as many villages and wards in their constituencies as they can.

“We have many problems on the ground,” said Kachin State People’s Party candidate Lum Zawng, who’s running for a Kachin State Hluttaw seat in the neighbouring constituency of Waingmaw-2. This seat is currently held by the National League for Democracy, the party that controls the state government and has the largest share of seats in the state hluttaw.

“Some villages in my constituency are far from the town and the roads are sometimes bad, but candidates are not allowed to stay overnight in villages,” he said, referring to a ban imposed as a local measure against COVID-19. “Travelling back and forth from the city is very time-consuming and ineffective.”

Still, in Myitkyina, national parties like the NLD and ethnic parties like the KSPP are pressing ahead by holding small gatherings and canvassing household by household.

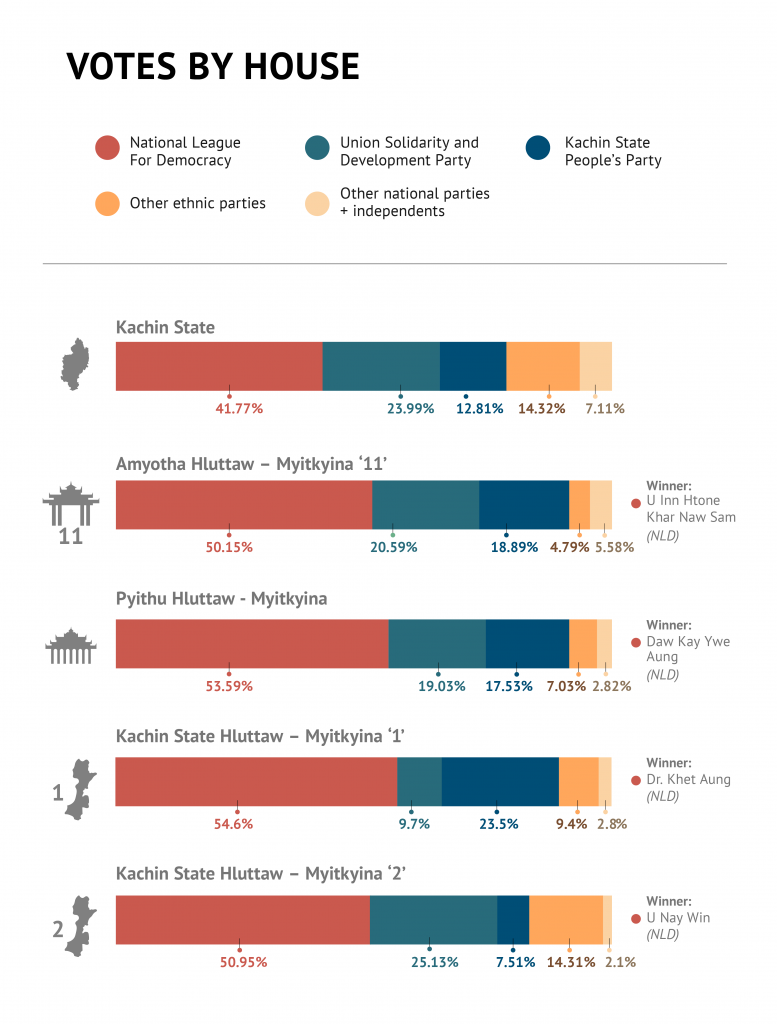

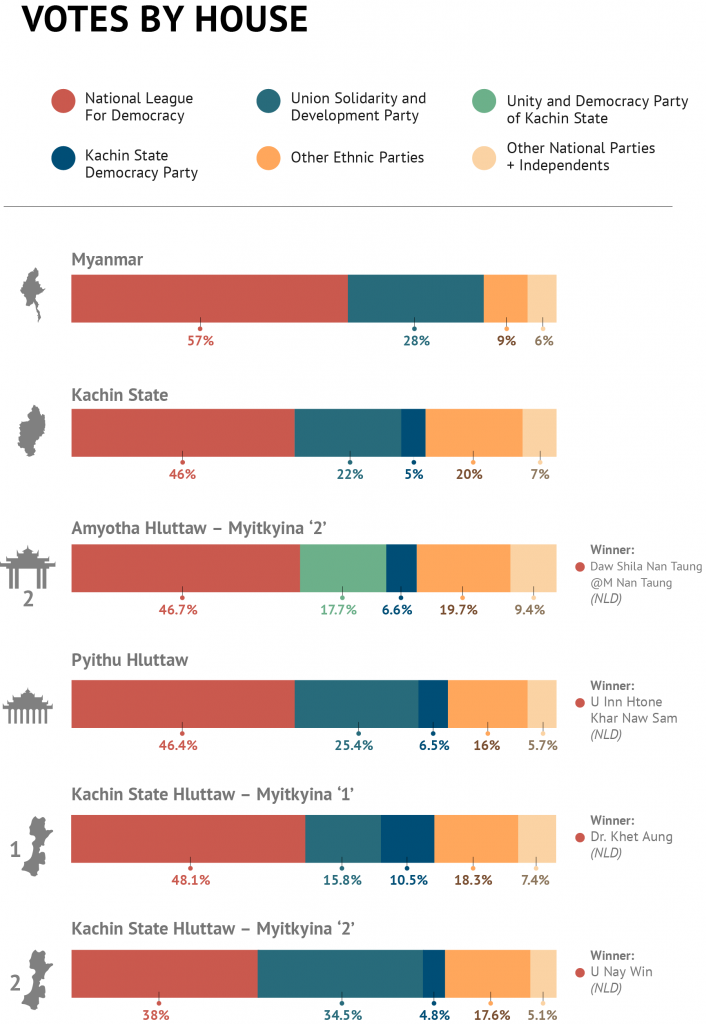

“NLD members from wards and villages who own spacious compounds are organising gatherings of up to 50 people,” the maximum number allowed by the health ministry, said Ndung Hka Naw, the party’s candidate for the Amyotha Hluttaw seat of Kachin-11, which encompasses Myitkyina and is currently held by the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party. “As well as following the instructions, we also provide masks and hand sanitiser to those who attend,” he told Frontier.

Other parties have resorted to vehicle convoys. Lum Zawng said younger KSPP supporters have been touring the township on bicycles and motorbikes.

National parties, however, have suspended vehicle convoys locally. Ostensibly this is a precaution against the spread of COVID-19, but in recent weeks there have been media reports of large NLD and USDP vehicle rallies elsewhere in Myanmar.

NLD candidate Ndung Hka Naw said the party is worried that convoys through downtown Myitkyina could attract crowds large enough to breach COVID-19 rules.

Chairperson for the USDP’s Myitkyina branch U Nyunt Win said the party has also suspended convoys for the time being.

The relatively small-scale campaigning in Kachin State has helped it to avoid ugly clashes between NLD and USDP supporters that have broken out elsewhere, mainly in Bamar-majority areas. The dust ups have received widespread criticism on social media.

“Parties here seem to be following the regulations and have resisted launching big campaign events that would raise health concerns among voters,” said Reverend Hkalam Samsom, president of the influential Kachin Baptist Convention. “I don’t see conflicts between the red and the green this time either,” he added, referring to the NLD and USDP by their colours.

But along with the perks of incumbency, the governing NLD’s name recognition infers it a greater advantage amid the pandemic restrictions, which make it harder for smaller and newer parties to raise awareness. In its campaign, the NLD has largely focused on the personality of its leader, State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi – a face familiar to all.

“The incumbent party automatically has advantages, and they are amplified during the pandemic,” said Lum Zawng. “Our feet are tied. [The election] is free but it is not fair.”

“Government officials are wearing [NLD] party badges and logos while distributing COVID-19 relief funds as if it is the party providing handouts to the people,” said Myitkyina Township USDP chairperson Nyunt Win.

Election observers and political analysts in Myitkyina told Frontier that the UDP, also known as the hninsi (rose) party because of its logo, is the most well-resourced party. But UDP campaign manager Ze Lum denied accusations lodged by some that the party has been handing out cash or promising jobs to people who’ve applied to join the party.

Hkalam Samsom said the UDP’s image was badly damaged after its chairperson, U Michael Kyaw Myint, was arrested on September 28 for escaping from police custody in the late 1990s.

Michael Kyaw Myint was until recently an obscure figure, before Myanmar Now published an expose on October 2 highlighting the party leader’s questionable past, which includes links to the United Wa State Army, an arrest in the 1990s for suspected money laundering and an escape from a Myanmar prison in 1999.

Campaigns in Myitkyina are also being fought on social media.

“I often stumble across ‘live’ campaigns on Facebook by KSPP candidates – especially younger ones like Seng Nu Pan – in which they deliver messages and information about the party and its candidates to voters,” said Mung San Aung, a journalist from Myitkyina who now lives in Yangon.

In addition to Facebook Live, Pyithu Hluttaw candidate for Myitkyina Seng Nu Pan, 26, told Frontier she uses Zoom to hold meetings with her constituents. The digital tools are “useful” because of the pandemic, she said, but they’re “not very effective since not all people have access to Facebook or [other communication apps] in our area.”

More than national parties, ethnic parties such as the KSPP, which was formed by a merger of several Kachin parties that competed in 2015, have focused on issues particular to the state. These include fighting drug abuse, resisting pernicious Chinese investment and amending the military-drafted 2008 Constitution to give states more autonomy.

On October 9, Doi Bu, the KSPP vice-chair, released a short video on Facebook introducing the party’s mission. Its ultimate objectives, she said, include lasting peace, a federal democracy, the termination of the Chinese-backed Myitsone dam project, which is located about 40 kilometres north of Myitkyina, and waging a war on drugs that includes rehabilitation for addicts. She said the KSPP will partner with other ethnic parties that have the same goals and policies.

Seng Nu Pan’s main priorities stem from her own work history.

“My background is in activism concerning IDP camps and women’s empowerment, and I am promising voters I’ll make progress on these issues when I am elected,” she said.

The KSPP and other ethnic parties have taken inspiration from the strong wins the Arakan National Party and the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy saw in Rakhine and Shan states, respectively, in the 2015 general election and subsequent by-elections.

“We aim to become a powerful third force on the path to a federal democratic union,” Seng Nu Pan told Frontier, suggesting that the two main forces in Myanmar politics now are the NLD, on one side, and the USDP-Tatmadaw alliance, on the other.

Lum Zawng said the KSPP hopes to win control of the state hluttaw so it can push for more autonomy and resource-sharing with the central government – even though the constitution gives the president the power to appoint the chief minister of Kachin regardless of which party wins the most seats in the state.

“KSPP candidates are contesting every constituency in Kachin State, except those for [non-Kachin] ethnic affairs ministers,” he said. “With 53 seats in the Kachin Hluttaw including 13 reserved for the military, we will control the legislature if we win 30 seats.”