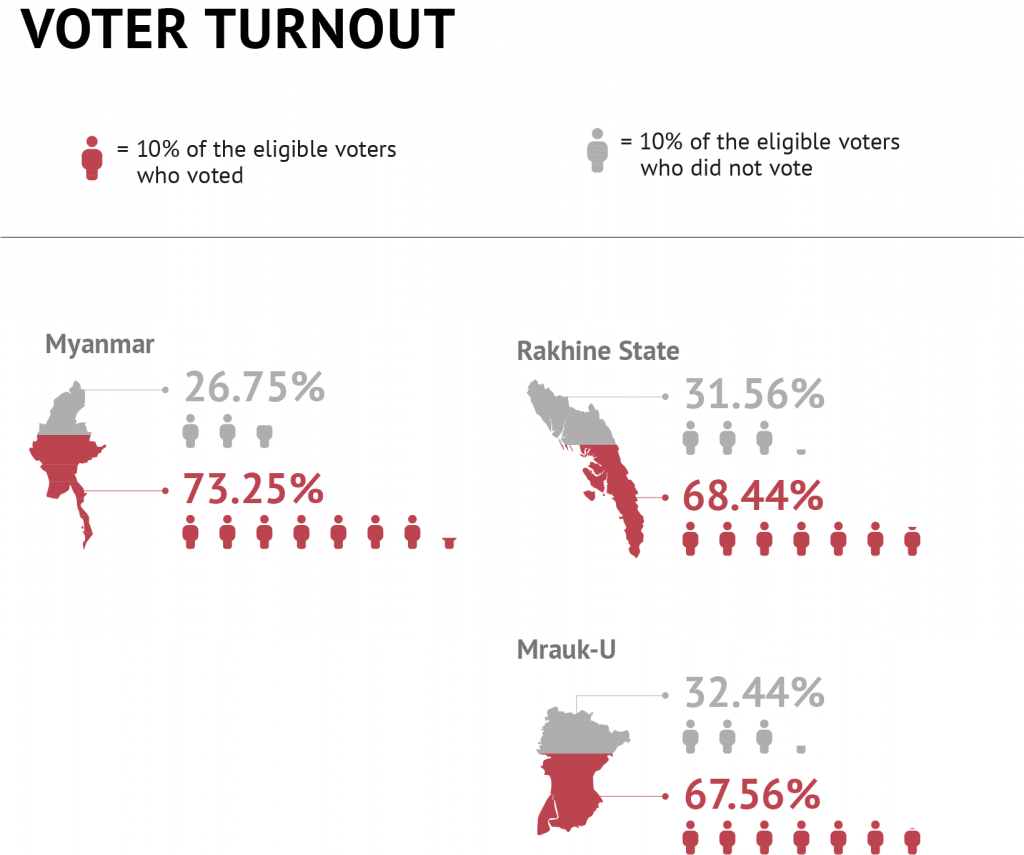

As the nation voted on November 8, the residents of Rakhine’s Mrauk-U Township had to watch from the side-lines, and many fear a lack of political representation will worsen conflict in the state.

This is the final article about Mrauk-U in Frontier’s Tale of Five Elections series. We have followed the election in five townships across the country, capturing events and local voices through the contest and its aftermath. Scroll down for the first two articles on Mrauk-U.

By KAUNG HSET NAING | FRONTIER

While voters across the country clustered in long queues under the scorching sun to cast their ballots on election day, the northern Rakhine State township of Mrauk-U was silent. No polling stations were open in the temple-filled former capital of the medieval Rakhine kingdom, and no fingers were dipped into blue ink.

“It was sadly just a normal day,” said U Htun Nay Win, the Arakan National Party’s candidate for the Pyithu Hluttaw before the Union Election Commission cancelled voting in Mrauk-U on October 16.

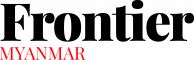

The Rakhine nationalist ANP won a plurality of seats in Rakhine in the 2015 election and was expected to retain a dominant position in the state with the November 8 vote, although the party had suffered splits since 2015 and was facing competition from rival Rakhine parties.

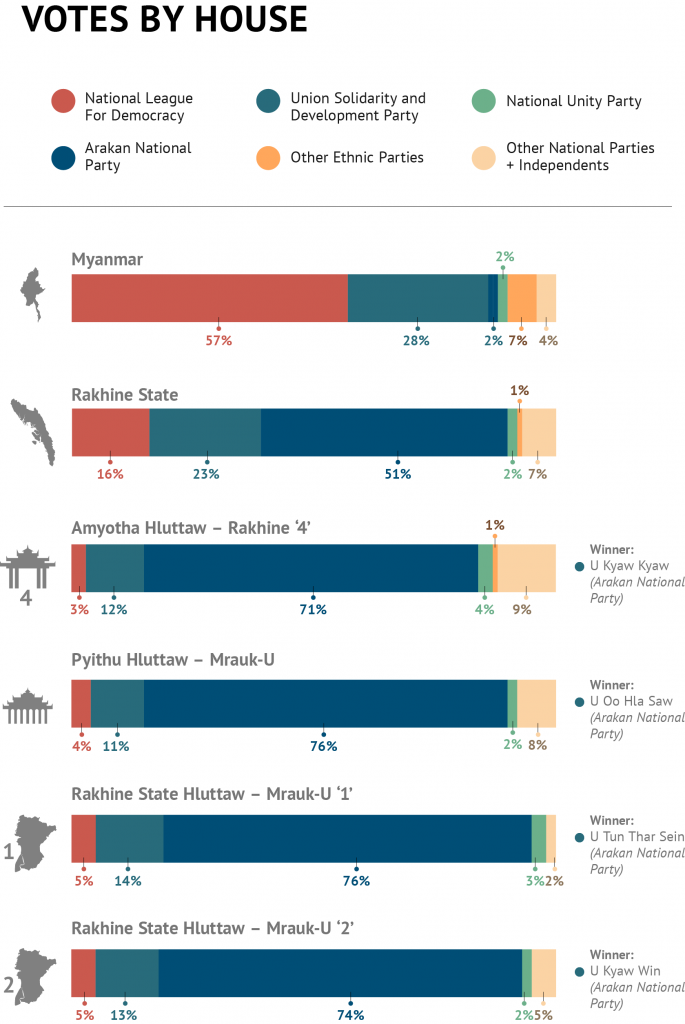

Voting was cancelled in Mrauk-U and eight other townships in the state, and in 152 wards and village tracts in four additional Rakhine townships, on the grounds of insecurity created by fighting between the Tatmadaw and Arakan Army. This deprived the ANP of most of its strongholds in the north and centre of Rakhine, while preserving predominantly NLD-voting areas in the south of the state, inviting allegations that the UEC had used the pretext of insecurity to gerrymander Rakhine to benefit the ruling party.

No fighting took place on November 8, Htun Nay Win said, but more than 1.2 million of the state’s 1.6 million eligible voters were still disenfranchised.

In Mrauk-U itself, 157,674 people were registered to vote.

“It feels bad being unable to vote when you’re watching voting take place across the rest of the country,” Ko Shwe Than Kyaw, a 26-year-old Mrauk-U resident, told Frontier on November 10. Before the vote was cancelled, he had trained as an election observer.

“It feels like democracy has been stolen from us,” he said.

November 8 would have been 22-year-old Ko Maung Maung Htay’s first time voting. He was ready to cast his ballot for the Arakan Front Party, founded by prominent Rakhine nationalist Dr Aye Maung after he quit as chair of the ANP in 2017. Aye Maung is currently serving a prison sentence for high treason for publicly accusing the NLD government of treating the Rakhine people “like slaves”. Only the AFP, Maung Maung Htay believes, could broker an end to the arbitrary killing and arrest of civilians that plagues Mrauk-U and elsewhere in the state.

“If a vocal candidate on these issues had been elected, maybe just a few positive changes could be made to our miserable condition,” he said. “Now we can only pray for less fighting and fewer arrests and killings in the days to come.”

In early November, the Rakhine Ethnics Congress, a civil society group, announced that more than 234,000 people in the state had been internally displaced by the fighting. Mrauk-U alone hosts more than 34,700 IDPs, 20,901 of whom are living in camps and 13,858 with host communities.

Even before the cancellation, there were no voter lists for camp residents. Although election sub-commission officials cited plans for special voting arrangements for IDPs, they said they would probably be unable to reach people displaced in rural areas, least of all those outside of camps.

“We wanted to vote like anyone else,” said U Htun Thein Maung, a 50-year-old resident of the Myo Thit IDP camp in Mrauk-U town. Given the chance, he said he would have voted for the ANP.

“I’m depressed,” ANP candidate Htun Nay Win said. “Under the 2008 Constitution, it was already hard to achieve self-determination – we know that. But we wanted our people to vote so the Rakhine people could at least have a voice. This year we couldn’t even do that.”

“This oppression will only further unite the Rakhine people,” he added.

Htun Nay Win and other Rakhine party candidates tried to follow the election results in the south of the state, where voting was allowed to go ahead, on November 8. But getting news was made difficult by the mobile internet ban, which the government continues to impose in seven townships in northern and central Rakhine, including Mrauk-U, and in Paletwa Township in neighbouring Chin State. The blackout began in June 2019 and service was restored at the beginning of August this year, but only at 2G speeds that make most web browsing and communication impossible.

“On election day I called [people in] Gwa, and then in Maunaung, then Taungup,” Htun Nay Win said. “We were very excited.”

U Maung Than Myint, the 62-year-old AFP Pyithu Hluttaw candidate for Mrauk-U before the vote was cancelled, said the same.

“I can’t get regular updates [on my mobile], but we can sometimes get internet for a minute here and there,” he said. “By the following night we had all the results from Rakhine State.”

These results would have provided some consolation to Htun Nay Win and Maung Than Myint. In the end, the ANP won four Pyithu Hluttaw, four Amyotha Hluttaw and seven Rakhine State Hluttaw seats, while the AFP won one Pyithu Hluttaw and two state hluttaw seats. The NLD, meanwhile, won five state hluttaw, one Amyotha Hluttaw and two Pyithu Hluttaw seats, and the Union Solidarity and Development Party won one state hluttaw and one Pyithu Hluttaw seat.

This means that, despite being hugely disadvantaged by the voting cancellations, the ANP remains the largest party in Rakhine, although even an ANP-AFP alliance would not create a majority in the state parliament once Tatmadaw representatives have filled their constitutionally mandated 25 percent quota of seats.

Significantly, Rakhine party victories included seats won by the NLD in 2015, in Taungup and Munaung townships, suggesting that Rakhine nationalist sentiment – or at least disaffection with the NLD government – has seeped southwards in recent years.

“Rakhine party wins in Taungup and Munaung are important, regardless of which [Rakhine] party it is. These seats moved from NLD into ethnic Rakhine hands, and we are very happy about that,” Maung Than Myint said.

While the NLD kept all its seats in the far-southern Rakhine townships of Thandwe and Gwa, Maung Than Myint said there was reason to expect that, in future polls, these too would fall to Rakhine parties. “The next step is, in coming elections, to ensure all seats [in Rakhine] are held by ethnic instead of national parties,” he said.

“We held a dinner with the ANP youth wing in Mrauk-U to celebrate our achievement in southern Rakhine,” Htun Nay Win said.

But the celebration was likely bittersweet. Many worry that without political representation, people in Mrauk-U and elsewhere in Rakhine will grow increasingly embittered, raising the likelihood and intensity of conflicts in the near future.

“If possible, we want by-elections to be held in Mrauk-U as soon as possible,” said Ma U Myint Yee, vice-chairperson of the Mrauk-U Youths Association.

On November 12 the AA declared a unilateral ceasefire until December 31 and called for elections to be held by the end of the year in parts of Rakhine where voting was cancelled, while offering its own assistance in conducting the polls. In an unlikely response, the Tatmadaw welcomed the AA’s call to fast-track by-elections in Rakhine and even said it would coordinate with the AA to make them happen.

However, electoral law bars by-elections from being held during the first and last year of a parliament’s term, meaning disenfranchised Rakhine voters will not be able to cast ballots until February 2022 at the earliest. Even if this rule were to be amended to allow for a much earlier vote, conflict between the AA and Tatmadaw remains intense, and it seems unlikely that the insecurity that prompted the voting cancellations in October would decline significantly in the next few months.

“I am worried we will have to go without representation for a long time,” said Htun Thein Maung, the 50-year-old resident of Myo Thit IDP camp.

“We need MPs. Now, we are like orphans.”