In the temple-strewn Rakhine State township, most would-be voters say they’re trying too hard to survive to take much interest in the November election.

This article is part of Frontier’s Tale of Five Elections series. We’re following the election through five townships across the country, capturing events and local voices through the campaign, voting and declaration of winners. Stay tuned for updates about Mrauk-U, as well as Mayangone in Yangon Region, Bawlakhe in Kayah State, Myitkyina in Kachin State and Pyawbwe in Mandalay Region.

By KAUNG HSET NAING | FRONTIER

The stone-brick Buddhist temples of Mrauk-U rival those of Bagan in splendour. Though often called “ancient”, they were built between 1430 and 1785, when Mrauk-U served as the cosmopolitan capital of the Arakan kingdom. In 2017, a commission appointed by the government to recommend solutions to conflict in Rakhine State urged the government to nominate the sprawling collection of ruins as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Former United Nations secretary-general Mr Kofi Annan, who chaired the commission, called Mrauk-U “arguably the greatest physical manifestation of Rakhine’s rich history and culture.”

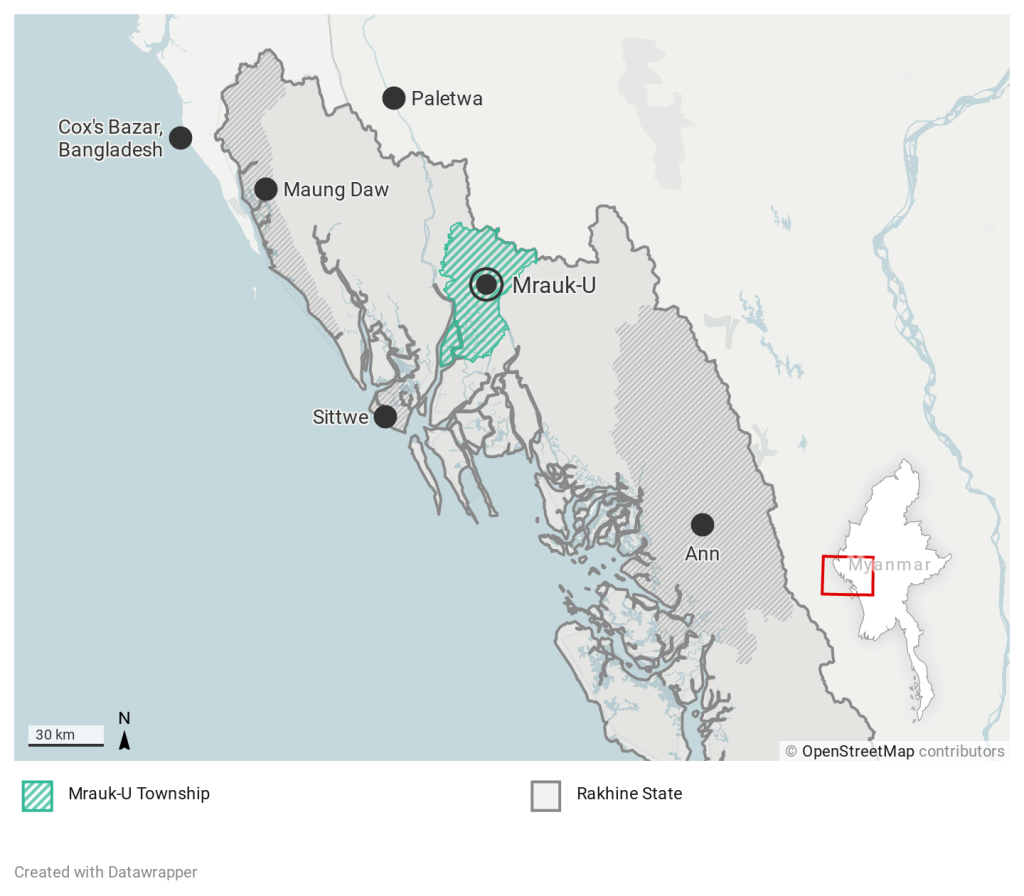

But for the last two years, the township in north-central Rakhine has been the scene of some of the most intense combat between the Myanmar military and the Arakan Army, which is fighting for greater political autonomy for the state. With ballots still set to be cast on November 8, the chance of being caught between the two warring groups’ fire has created an atmosphere of fear among voters, candidates and election officials.

Tatmadaw troops perch on the hills surrounding the town and man checkpoints on all main roads leading in and out of it. Military columns regularly march through the urban centre, and a 9pm-5am curfew has been in place since April last year. A particularly fierce battle in July saw the military carry out airstrikes in the area.

The township has also been subject to a mobile internet blackout since June last year – imposed by the government ostensibly to disrupt the AA’s operations but criticised by human rights groups as a cover for human rights abuses by the Tatmadaw. 2G service was made available in August this year, but Frontier found it to be virtually unusable.

“Here, you travel at your own risk,” said Daw Thida Khaing, 36, secretary of the Mrauk-U Township election sub-commission.

“Village [tract] election sub-commission members might plan to come to town, but on the way here, they hear news of something happening and turn back,” she said, referring to the many sudden eruptions of conflict in the township.

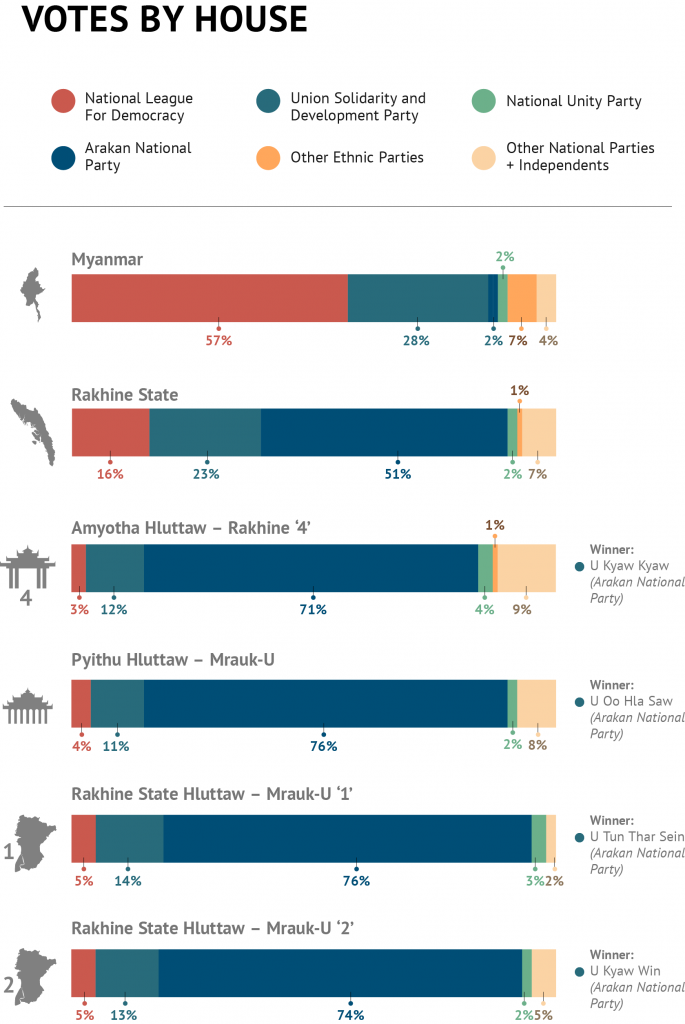

Interest ran high during the 2015 election, when support for the ANP was strong. The party won 22 of the 35 elected seats in the state’s 47-member assembly. But that excitement turned to resentment after the election, when then-president U Htin Kyaw – who the constitution gave the authority to appoint state and regional chief ministers – chose U Nyi Pu, a member of the National League for Democracy, as Rakhine State chief minister.

The NLD had won just nine seats in the state hluttaw, and besides the position of Chin ethnic affairs minister, these NLD victories were confined to southern townships, where Rakhine nationalism is weaker. For ANP voters elsewhere in the state – such as in Mrauk-U, where the NLD received only about 5 percent of the vote – the appointment of Nyi Pu as chief minister felt like a slap in the face. For some, it must have sounded a distant echo with 1785, when the Bamar Konbaung Dynasty conquered the Arakan kingdom.

The 2014 census put Mrauk-U Township’s largely rural population at 189,630, but the General Administration Department has more recently counted 244,981 residents. Of these, 87pc are ethnic Rakhine, but with the township sharing a border with Chin State to the north, there are also about 4,500 ethnic Chin residents, according to the GAD.

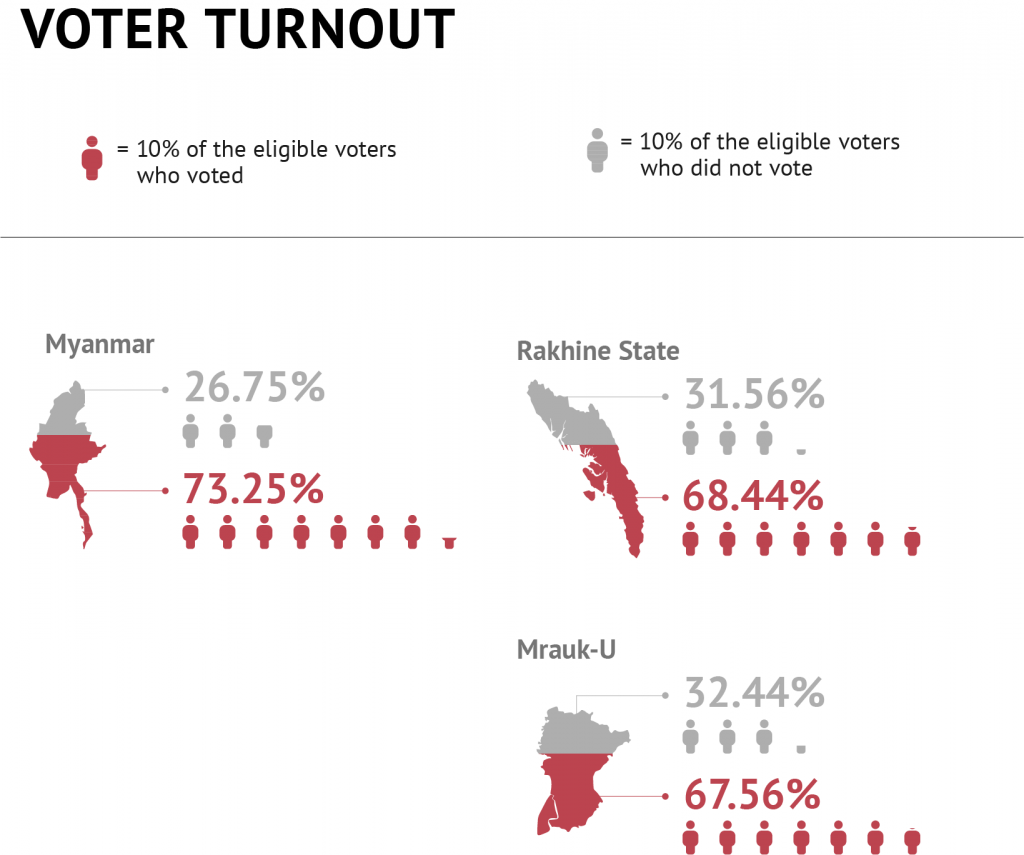

Nearly 68pc of the township’s 141,446 eligible voters cast their ballots in 2015, mostly for the ANP, which won about 75pc of votes cast in Union and state hluttaw races. The Tatmadaw-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party came a distant second, with just a little more than 10pc of votes.

But the cost of the violence that has since engulfed the township has eroded most interest in the November election. Several of Mrauk-U’s historic temples – once seen as a possible tourism lifeline in the impoverished area – are strafed with bullets. There are 26 camps sheltering about 18,000 people displaced by the conflict. Some of these camps are at the foot of the town’s most significant temples, including the Shittaung (built in 1535), named after its 80,000 Buddha images, the Htokekathein (1571) and the Laymyathnar (1430).

Just 30pc of this year’s 157,674 eligible voters checked preliminary voter lists for errors or omissions, and only about 200 had made corrections to their entries, according to data from the township election sub-commission in late August.

In teashops and restaurants in the town, most talk was of the armed conflict and the AA. When Frontier entered, the chatter would die down but quickly resumed once people concluded we were safe. The upcoming election, however, was barely spoken about, and the young people climbing hills around the town for rare snatches of mobile internet signal were mostly seeking news of the war rather than the vote.

“Most people think it will make no difference if they vote. They’re not interested in the election,” said Ma U Myint Yi, the 26-year-old vice-chair of the 290-member Mrauk-U Youths Association, which runs youth development programmes and assists internally displaced people.

She said most are preoccupied with the ongoing conflict, the “second wave” of COVID-19 cases that began in Rakhine in mid August, and their own struggle to make a living. Electoral politics seems to offer few answers to these problems.

She said most people are unhappy with their current MPs’ performance, but that, for now, disinterest outweighs dissatisfaction.

Twenty-four candidates from seven parties, including the ANP, Arakan Front Party, USDP and NLD, are contesting seats in the township. The splintering of Rakhine nationalist politics since 2015 has made the result hard to predict, with a fierce contest expected between the ANP and the AFP, whose leaders broke away from the ANP in 2018.

The AFP’s founder, former ANP chair Dr Aye Maung, was sentenced in March last year to 20 years’ imprisonment for high treason after accusing the Bamar-dominated National League for Democracy government in a public speech of treating Rakhine people like “slaves”. In May the Union Election Commission annulled his status as a Pyithu Hluttaw MP for Ann Township because of the conviction, but he still receives widespread support in north and central Rakhine.

The ANP chose U Htun Nay Win, 36, to contest the township Pyithu Hluttaw seat for Mrauk-U after the incumbent, prominent party member U Oo Hla Saw, decided not to seek re-election. Htun Nay Win will face off against the AFP’s U Maung Than Myint, 62.

Daw Mi Shwe Phyu, 55, owns the Moe Cherry restaurant in downtown Mrauk-U. She laughed when asked whether future MPs might be able to solve any of her problems.

Her restaurant, which for nearly 20 years has mainly served foreign tourists visiting the historic temples, earned K1 million a day before December 2018, when fighting escalated. Earnings have dwindled over the past two years because of the fighting.

“I want our township to be peaceful, because only then will tourists come back and our restaurant be able to do good business again,” she told Frontier from her empty restaurant.

She’ll vote for a Rakhine-based party but has not yet decided which – whichever one prioritises peace and development, she said. Still, her expectations for progress are low.

November will be 22-year-old Ko Maung Maung Htay’s first time voting. But the young electronics repairman, who lives in the town’s Myothit ward, has not checked his entry on preliminary voter lists.

He said he wants an MP that can stop the Tatmadaw from harassing and detaining civilians.

“When we go to the market, there are Tatmadaw soldiers, and they often interrogate young men like me. If they want to take us with them we can’t do anything about it,” he said. “We want politicians who can solve these kinds of problems.”

For him, that looks most like Aye Maung’s party, the AFP.