Prominent female activists in Myanmar have dedicated their lives to challenging discriminatory social and cultural conventions.

By CHARLOTTE ENGLAND | FRONTIER

“I was born feminist,” insisted Daw Pyo Let Han, 35, sitting in her small office on the second floor of a narrow building in downtown Yangon. “I always questioned traditional norms, like that women’s longyis are dirty. Most people think women are equal to men in our country, but I never thought that was true because in the religion and the culture women are always subordinate to men.”

Last year, Daw Pyo Let Han launched Myanmar’s first feminist magazine, Rainfall, with three other women activists. She is also the author of three novels about women’s experiences in Myanmar.

“I like to break out of the traditions and the cultural and social norms. I make women think about their social status as second class citizens,” she said, describing her novels as “shock therapy”. “I think I wrote the first book in Myanmar about the love between two women,” she said.

Daw Pyo Let Han is part of burgeoning feminist movement in Myanmar, an organic strand of women’s activism that is thriving outside party politics. The movement is creative and thoroughly modern, clever, adaptive and diverse, and explicitly intersectional. Slowly but surely it is gaining traction and helping to change the restrictive gender norms that have a quiet grip on Myanmar’s women, and are all the more insidious for their subtlety.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“Myanmar women are perceived as enjoying equality in society,” said Daw May Sabe Phyu, 39, director of the Yangon-based Gender Equality Network. “But the majority of the decision makers at the parliament, at the judicial systems, at the administrative bodies [are men],” she said. “We see very few women obtaining leadership positions. Women [do not have] access to equal pay and equal opportunities. The existence of widespread violence against women also shows strong discrimination.”

Discrimination against women is much more difficult to tackle because it is rarely acknowledged, said Daw May Sabe Phyu. But increasingly, women activists are finding ways to highlight and counteract discrimination.

Daw May Sabe Phyu, director of the Gender Equality Network. (Charlotte England / Frontier)

Daw Htar Htar, 43, runs Akhaya Women, an organisation that offers women “empowerment through sexuality dialogue” — essentially a safe space in which women can meet to discuss sex, gender and their bodies.

“We address practices, norms and beliefs that put women as second [class] citizens, [with] lower status,” Daw Htar Htar said. “For example, everybody in Myanmar thinks our menstrual blood is dirty. And we cannot wash our longyi together with men’s clothes, we cannot iron it together. If they touch [a woman’s longyi], men will lose good luck. The message given daily is women are low.”

Akhaya’s discussion groups began spontaneously, with Daw Htar Htar chatting to friends in her living room. The sessions are still informal and relaxed, but Daw Htar Htar plans to expand the project and is training more facilitators. There is also discussion about taking the program into schools.

“Especially for girls and women there is no way to learn about sex and sexuality and many of us don’t touch or see or look even at our own body,” Daw Htar Htar said. “When we learn about our own body, very simple facts about our own body, we feel so empowered.”

Daw Htar Htar, one of the founders of Akhaya Women. (Charlotte England / Frontier)

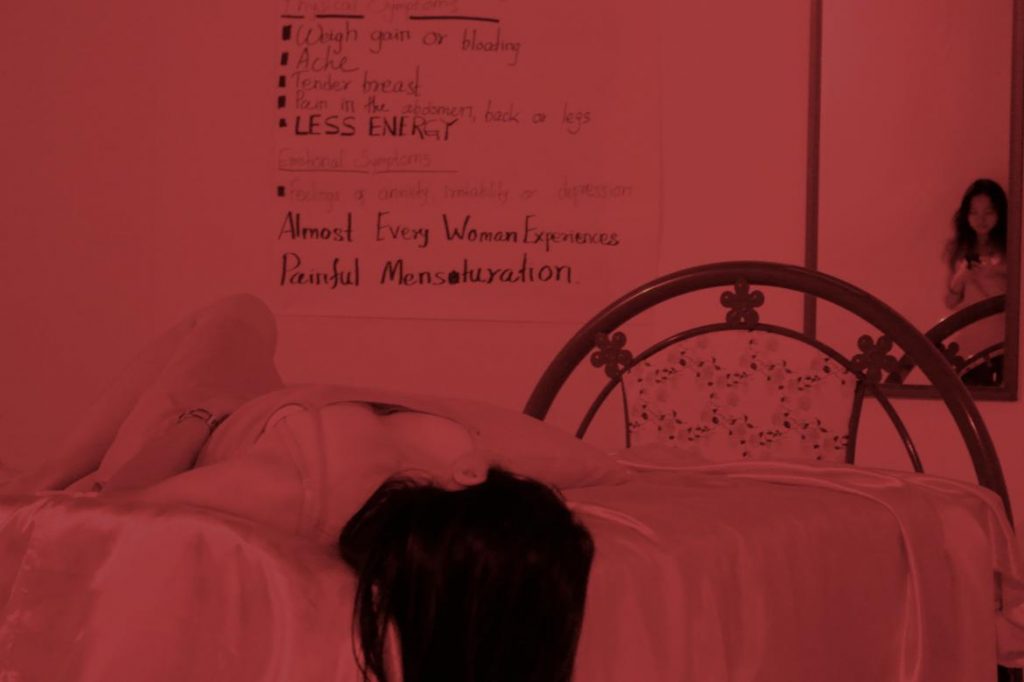

Performance artist Ma Ei, 37, is also challenging the oppressive silence surrounding women’s bodies, in an unconventional way. The inspiration for her latest art installation was the dismissive reaction of a male friend to her complaining about feeling very tired during her period. She was so annoyed she decided to spend three days lying in a blood-red room for an installation entitled “Period”.

“I wanted to remind men: ‘We have this, you should care, you should respect women’,” Ma Ei said, adding that she also wanted to occupy a space and set aside a time for women to talk about an issue that is rarely discussed in Myanmar, where — as Daw Htar Htar said — periods are considered unclean.

Although “Period” was the first time she tackled such a taboo subject, Ma Ei often channels her frustration at the routine subjugation of women in Myanmar into powerful performance art pieces.

“I did a show where I dress like a man and then I cook. And sometimes I just put cooking utensils in front of me on the table and I don’t do anything, I just sit and watch,” she said, explaining that women of her generation were encouraged to marry young and to have babies instead of pursuing careers, and that at home women are expected to do all of the work. “Most of the women are just housewives. Even if they have a job, when they come back home women have to do everything, all the housework,” she said.

Initiatives such as “Period”, and to an extent Rainfall magazine, risk being inaccessible to most Myanmar women and remain the domain of a privileged few in Yangon. Ma Ei admits that her family in Dawei has no idea what she does and would not understand if it did. But there is a decisive push to be inclusive. The Rainfall staff, for example, are working to establish a distribution network so subscribers can receive the magazine throughout the country. Daw Pyo Let Han emphasised that the aim of the publication is to promote feminism at all levels, including in villages.

There are also women activists working with an explicitly intersectional agenda. In Chin State, I joined Daw Cheery Zahau, 34, on the campaign trail last year while she competed in the national election as a candidate for the Chin Progressive Party. We travelled between remote villages, on foot or by motorcycle when the steep mountain paths were too narrow and decrepit for cars. Daw Cheery Zahau has been educating remote communities about their rights, democracy, and specifically about women’s issues, as an activist for more than a decade, since she co-founded the Women’s League of Chinland in 2004.

Daw Cheery Zahau, co-founder of the Women’s League of Chinland. (Charlotte England / Frontier)

“According to the UNDP survey in 2011, the poverty rate in the whole country is 26 percent and in Chin State it’s 73 percent,” she said, adding that there is a complex relationship between poverty and sexism. “Even when there is income, most of the income is earned by men. Women always remain at home and they work in the farms or they take care of the family. They never have a chance to generate income.”

With the WLC, Daw Cheery Zahau has travelled extensively in Chin State, delivering humanitarian aid and establishing small development projects that aimed to empower women.

Back in Yangon, Daw Wai Wai Nu, 29, echoes Daw Cheery Zahau’s sentiments, emphasising the intersectional discrimination faced by Rohingya women.

“My passion is to work on youth and women’s issues generally,” Daw Wai Wai Nu said, “but after the conflict happened in 2012, I realised that there are very few organisations working on the Rohingya and talking about the Rohingya, and there are no organisations working with the Rohingya women. I had to do something.”

Daw Wai Wai Nu said that she could not collaborate with Muslim or Rohingya men’s groups, because most of them were “quite sexist”. She established the Women Peace Network of Arakan, which advocates for change at both the grassroots and parliamentary levels, and pr motes “mutual understanding” and peace between women and youth from different ethnic groups.

“Regardless of your status or your ethnicity or your gender,” said Daw Wai Wai Nu, “you should have the same rights and dignity as a human being.”

Title photo: A scene from performance artist Ma Ei’s provocative art show, “Period”. (Charlotte England / Frontier)