In the first in a two-part series, Frontier’s senior correspondent Mratt Kyaw Thu journeys across central Myanmar to study the history and legacy of the country’s long and complex relationship with Islam – and meet the many Muslims who are eschewing conservative strains of the religion.

By MRATT KYAW THU | FRONTIER

Photos TEZA HLAING

AN ELDERLY man in a faded longyi and a casual shirt offered a friendly “hello” through betel-stained teeth as I approached the mosque in the former royal capital of Amarapura, on the southern outskirts of Mandalay.

He introduced himself as U Nyi Hla, 71, and then took a few minutes to recall his Muslim name. “I hardly remember my religion name, but it’s … uh … it’s Abdul,” he said with a smile.

Nyi Hla, who does not wear a beard, has been the imam – the man who leads prayer services – at the Kalapyo (Young Muslims) Mosque for 12 years.

The mosque is more than 200 years old and was built soon after Konbaung dynasty monarch King Bodawpaya established Amarapura as the royal capital in 1783.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Bodawpaya was the first Burmese king to officially recognise his Muslim subjects by royal decree, wrote Ba Shin in The Coming of Islam to Burma down to 1700 A.D., published by the Burma Historical Commission in 1963.

The Kalapyo Mosque, on the Mandalay-Amarapura Road, is one of about 40 that were built on Bodawpaya’s orders for the young Muslim soldiers who served in his Royal Defence Army.

In my years working as a journalist I’ve entered countless mosques throughout Myanmar; as a non-Muslim, I’m always careful about how I act, in order not to inadvertently cause offence.

But when I entered the Kalapyo Mosque, I felt instantly at ease. Everything was familiar; in fact, with no sign to identify it as a mosque, it could easily be mistaken for a monastery.

Traces of Islam

I had travelled to Mandalay in an effort to learn more about Myanmar’s Muslim community: its past, present and future. The standard tropes – a beleaguered minority living in fear of hard-line nationalists, according to international media; a dangerous, almost existential threat to Buddhism in the eyes of nationalists – soon melted away. What was revealed was a vibrant, inclusive, well-integrated and peaceful community.

Amarapura was a natural place to begin my journey. As well as Kalapyo Mosque, other Muslim places of worship had been built in the former royal capital on Bodawpaya’s orders; these included the earthquake-damaged Oh Daw Mosque – its windows, entrance and sacred places decorated in the Burmese arabesque style – and the Koyandaw (Royal Bodyguards) Mosque.

A shrine, or dargah, in Amarapura honours Abid Shah Hussaini, a learned Muslim believed to have come from Afghanistan who was appointed by Bodawpaya to adjudicate in disputes involving members of the Islamic community.

Another tomb in the compound of Hussaini’s shrine honours U Bein, a local Muslim official who built the famous teak bridge of the same name completed in 1851 that spans the nearby Taungthaman Lake. During the reign of the ninth Konbaung monarch, King Bagan Min (1846-1852), U Bein and another prominent Muslim citizen of Amarapura, its mayor Bai Sab, were executed.

Teza Hlaing | Frontier

The neglect of Amarapura’s Islamic heritage is all too clear, though. Some of this is by government diktat: Since 2007, for example, Muslims have been prohibited from rebuilding the shrine to U Bein, which is only a short distance from the bridge named in his honour that attracts tourists from around the world.

But when Mindon shifted the capital to Mandalay, many simply moved away from the area. Nyi Hla said about 50 men attend Friday prayers at the Kalapyo Mosque because it was the only one in the area; many others are dilapidated and too old to use.

As we walked around the mosque and talked, Nyi Hla gazed off into the distance, as if staring into the past. “There were lots of Muslim households around here when the king moved his capital to Mandalay, but later because of many causes, Muslims also moved to another places,” he said. “Everything’s changed later… yes, everything’s changed.”

Communal ties and tensions

Nyi Hla is a typical representative of Muslims who have lived in Myanmar for generations and have integrated into culture and society. The 2014 census counted 1,147,495 Muslims, or 2.3 percent of an enumerated population of 50,279,900.

A further 1,090,000 Muslims in Rakhine State were not counted because they refused to be identified as “Bengali”; if included, Muslims would comprise 4.3 percent of the population, up only slightly on the 3.9 percent recorded by the previous census, in 1983.

There is only one Muslim group among the 135 officially recognised ethnic nationalities. Known as the Kaman, they are thought to number around 45,000 nationally.

The rest have adopted a variety of names. The most well known are the Rohingya, whom the government and most Myanmar insist be called Bengali, but there are many others from various parts of South Asia and the Middle East. Some have unique ethnic identities, like the Panthay, who are originally from southern China, or the Cholia, who are Tamil-speaking Muslims from Tamil Nadu in southern India. Many others though simply call themselves Myanmar, Burmese or Bamar Muslims.

The census revealed that the biggest Muslim populations are in Yangon and Mandalay regions and Mon State. There are 345,612 Muslims in Yangon Region (comprising 4.7 percent of the population), 187,785 in Mandalay Region (three percent) and 119,086 in Mon State (5.8 percent).

Communal relations in Myanmar have been strained since 2012, when the violence that engulfed Rakhine State was followed by bloodshed elsewhere, including rioting at Meiktila in 2013 in which scores were slaughtered, including 30 students at a Muslim boarding school.

Men pray at Taung Balu Mosque in Mandalay (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

The violence has coincided with a rise in Buddhist nationalism that has destroyed previously harmonious relationships between friends, neighbours and entire communities.

It has become rare to see a Buddhist in a Muslim shop, or vice versa, in Yangon and in large towns in central Myanmar, such as Meiktila.

The exception is Mandalay and its surrounds, where community relations are warmer and there has historically been none of the tensions that sparked violence in Yangon, such as the deadly rioting in 1930 involving Burman dockworkers and Indian labourers.

Although Mandalay was hit by communal conflict in July 2014, leaving two people dead, many argue that the incident in fact highlighted the social cohesion in the city. Community groups, religious leaders and residents mobilised to calm tensions and combat what they said were attempts by outsiders to foment conflict following inflammatory social media posts by U Wirathu. The posts accused Muslim teashop owners of raping a Buddhist women – an allegation later shown to be false.

“The scripted sequence that played out in Mandalay was similar to the pattern of previous outbreaks of violence, but with one crucial and telling difference – local people refused join with the rioters,” US-based organisation Justice Trust wrote in a March 2015 report on the July 1-2 violence.

The rioters visited two monasteries after midnight in order to recruit monks to their cause but were rebuffed by senior abbots, the report said. “Meanwhile, activists from a local multi-faith alliance called the Mandalay Peace Committee and monks from the All Burma Monks Union responded quickly, alerting their networks and establishing a presence on the streets, thereby helping to limit the scope of damage.”

In a radio address on July 7, 2014, President U Thein Sein expressed appreciation to Mandalay residents for preventing the spread of violence in their city despite the efforts of those seeking to instigate conflict. He described Mandalay as “a model society” where people of all faiths have lived alongside each other for many decades “keeping in mind they all are Mandalay residents”. Because of the riot, “Mandalay people could show their unity and mutual trust among communities,” he said.

One of those who mobilised to keep the peace in July 2014 was Ko Than Swe, a Muslim businessman who was born in the city. He worked with Buddhist monks and other religious and community leaders to keep people calm.

He said this was made easier by the fact that people of different faiths lived and worked alongside each other in Mandalay; unlike Yangon, there is no ward or township in urban Mandalay where one religious community is totally dominant.

“When we were growing up, we spent a lot of time in Buddhist monasteries – we played in the monasteries and are familiar with Buddhism, as are many other Muslims in Mandalay,” he said.

A man cleans his hands before attending Friday prayers at Taung Balu mosque in Mandalay (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

The history of tolerance and assimilation in Mandalay may be a legacy of inclusive Konbaung dynasty kings.

The popular, modernising King Mindon, who established Mandalay as Burma’s last royal capital in 1857, permitted a mosque to be built inside the palace walls and funded a guesthouse in Mecca for Muslims performing the Hajj.

Many of the mosques and Chinese and Hindu temples in Mandalay were built during Mindon’s reign from 1853 to 1878.

They include the June Mosque on 27th Street built by U Bo, one of two Muslims who had supported the rebellion led by Mindon and his brother, Prince Kanaung, that overthrew Bagan Min and installed Mindon as king. The other Muslim, U Yuet, became the head chef in Mindon’s palace.

U Hla Win, 78, is descended from the Kalapyo soldiers who served royalty; his great-grandfather on his mother’s side served as a major with an artillery unit. Hla Win, who worked part time as a township judge during the Ne Win dictatorship, is a vegetarian who does not have a Muslim name and is moderate in his beliefs.

“I believe in Allah and the Prophet Mohammed and I follow the rules and doctrines of the Quran but I don’t like what some Muslims are doing nowadays,” he told me.

‘Our lord is powerful’

There are wide variations in the beliefs of Muslims, as there are among Buddhists. Theravada Buddhism prevails in Myanmar, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Sri Lanka, with Mahayana Buddhism dominant in northern and eastern Asia, and Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet.

Although the Quran prohibits the worship of images of people or other living beings, moderate Muslims in Myanmar and throughout the world throng dargah to offer prayers.

The Abid Shah Hussaini Dargah in Amarapura and the Lushah Dargah, at Tabetswe in Sintgaing Township, about 30 kilometres from downtown Mandalay, are popular pilgrimage sites for devout Muslims in central Myanmar.

A woman, her face and hair uncovered, prays at the Lushah Dargha (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

“Many people come here to pray, even Buddhists and Christians, as our lord is powerful,” said U Aye Ko, 51, chairman of the Lushah Dargah trustees, whose Islamic name is Mohamed Abishair.

When I visited in March, Buddhist children were playing in the dargah’s shaded compound, which covers about three acres. In front of the shrine a woman was praying; I was surprised to see that she did not wear any covering on her face or hair.

Aye Ko, the trustee, was unable to provide precise information about the origins of the dargah, but said it was named after a Muslim missionary, Lushah, from Central Asia from the early or mid 19th century. Visitors believe if they pray at the dargah their wish will be fulfilled.

Aye Ko and most other Burmese Muslim elders in Tabetswe dress as Burmese. They wear neither beards nor the long, collar-less shirts known as kurta that are traditionally worn by Muslim men in South Asia. The archway at the entrance of the Lushah Dargah, one of the biggest Muslim buildings I’ve encountered in my trips to central Myanmar, is decorated with Burmese-style sculptures.

Tabetswe has 1,000 Buddhist and Muslim households and the two communities coexist harmoniously. When I visited the village early one evening, the call to prayer at the mosque mingled with the sound of a recorded monk’s sermon being played at a monastery.

“Religion is just religion here,” said Aye Ko. “Buddhist children use the land [in the mosque] as a playground and Muslims go the monastery when there is an event to give donations.

“When there has been [communal] violence elsewhere in the country it has never affected our village and it will never happen to us.”

‘We are Burmese Muslims’

With a few exceptions, the Burmese Muslims in central Myanmar have been able to live peacefully with their neighbours because they have embraced Burmese culture. But elders worry about the influence of more conservative strains of the religion from the Subcontinent and the Middle East. The result has been a growing embrace of orthodox Islam and they suspect this has also been a factor in recent communal conflict, alongside the rise of Buddhist nationalism.

“In Yangon and some other heavily Muslim townships, they’ve been changing,” said Muslim author and teacher U Aung Aung Than. A Mandalay resident, he said that Muslim communities in most parts of central Myanmar remain well integrated. “We upper Myanmar Muslims are Burmese Muslims. We love Burmese culture and at the same time we pray to Allah and follow the doctrines of the Quran.”

During three weeks in central Myanmar, I met dozens of people who proudly introduced themselves as “Burmese Muslims”. Hla Win, the retired judge, said, “I told my grandsons that religion is just a description; humans are equal whether they are Muslims or Buddhists. But I’m worried that Muslim attitudes are changing because of outside interference.”

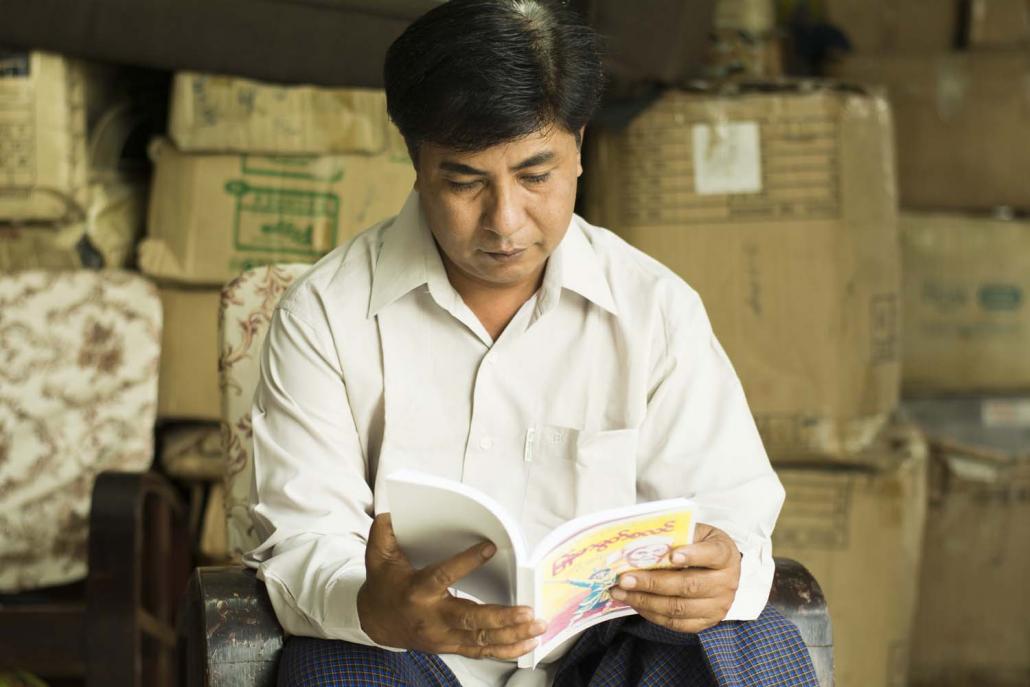

U Aung Aung Than (Teza Hlaing | Frontier)

My journey through central Myanmar journey was winding down, but one of my last interviews was the most startling.

I travelled to the Taung Balu Mosque in Mandalay to interview the imam, U Toe Moe Aung. Everyone in the mosque referred to him by this name; he only revealed later, at my questioning, that his Muslim name is Nayzwe Mudding.

The mosque is unusual in Mandalay because men and women do not pray together; instead, a separate prayer room is provided for women.

Toe Moe Aung was wearing a traditional Rakhine longyi, which Burmese men often don to mark special occasions. When I asked about his attire, he responded simply: “Our holy Quran doesn’t specify exactly what to wear. It only says that it should be ‘suitable and flexible with your place’.”

It is one teaching that many Muslims in central Myanmar have clearly taken to heart.