The deputy leader of the Arakan Army tells Frontier in the border town of Laiza in Kachin State about the group’s shift in focus to Rakhine State and why the Rakhine people may have to endure more suffering in the years ahead.

By YE MON | FRONTIER

Photos HKUN LAT

THE SECURITY situation in Rakhine State continues to worsen as fighting between a defiant Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw spreads to more townships, claiming more lives on both sides and displacing thousands of frightened and anxious villagers.

Shortly before the latest flare-up in fighting, Frontier interviewed the Arakan Army’s deputy chief, Brigadier-General Nyo Tun Aung, near Laiza, the town on the Chinese border where the Kachin Independence Organisation has its headquarters.

Speaking from what he described as the group’s temporary headquarters, Nyo Tun Aung discussed the motivation and ambition behind the AA’s Independence Day attack, its alleged links to the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army and the decision to shift its headquarters to Rakhine State.

Later the same day, AA forces in Rakhine State staged an assault on a police outpost in Ponnagyun Township’s Yoetayoke village, which state media said left nine police officers dead.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

The attack precipitated a fresh wave of conflict that has spread to urban areas, including the historic town of Mrauk-U, once the capital of an independent Arakan kingdom.

Pre-emptive strike

Nyo Tun Aung characterised his group’s January 4 attack on four police stations as a defensive action in response to a build-up of Tatmadaw forces in northern Rakhine State.

He said that in October and November 2018, two elite Tatmadaw divisions, the 22nd and the 55th Light Infantry Divisions, had trained in Bago Region in preparation for deployment to Rakhine to strike at the group.

The Tatmadaw had begun deploying more troops to Rakhine and border areas of neighbouring Chin State, where the group is known to have bases. The AA had learned about planning for the operation from Tatmadaw soldiers it had captured, Nyo Tun Aung said.

He also pointed to the Tatmadaw’s announcement on December 21 that it was suspending operations in five regional commands in northern Myanmar until April 30 as further evidence of an imminent campaign. While the Tatmadaw said the unilateral ceasefire was announced in order to pursue talks with groups yet to sign the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement, it excluded the Western Regional Command, which covers Rakhine State.

Shortly afterwards came the brazen AA raid on security posts in northern Rakhine on January 4, Independence Day, that left 13 policemen dead and resulted in the government’s order at a high-level security meeting three days later for the Tatmadaw to “crush the terrorists”.

Nyo Tun Aung said the large cache of weapons and ammunitions that AA forces seized from the police stations was further evidence of a build-up of forces in the state.

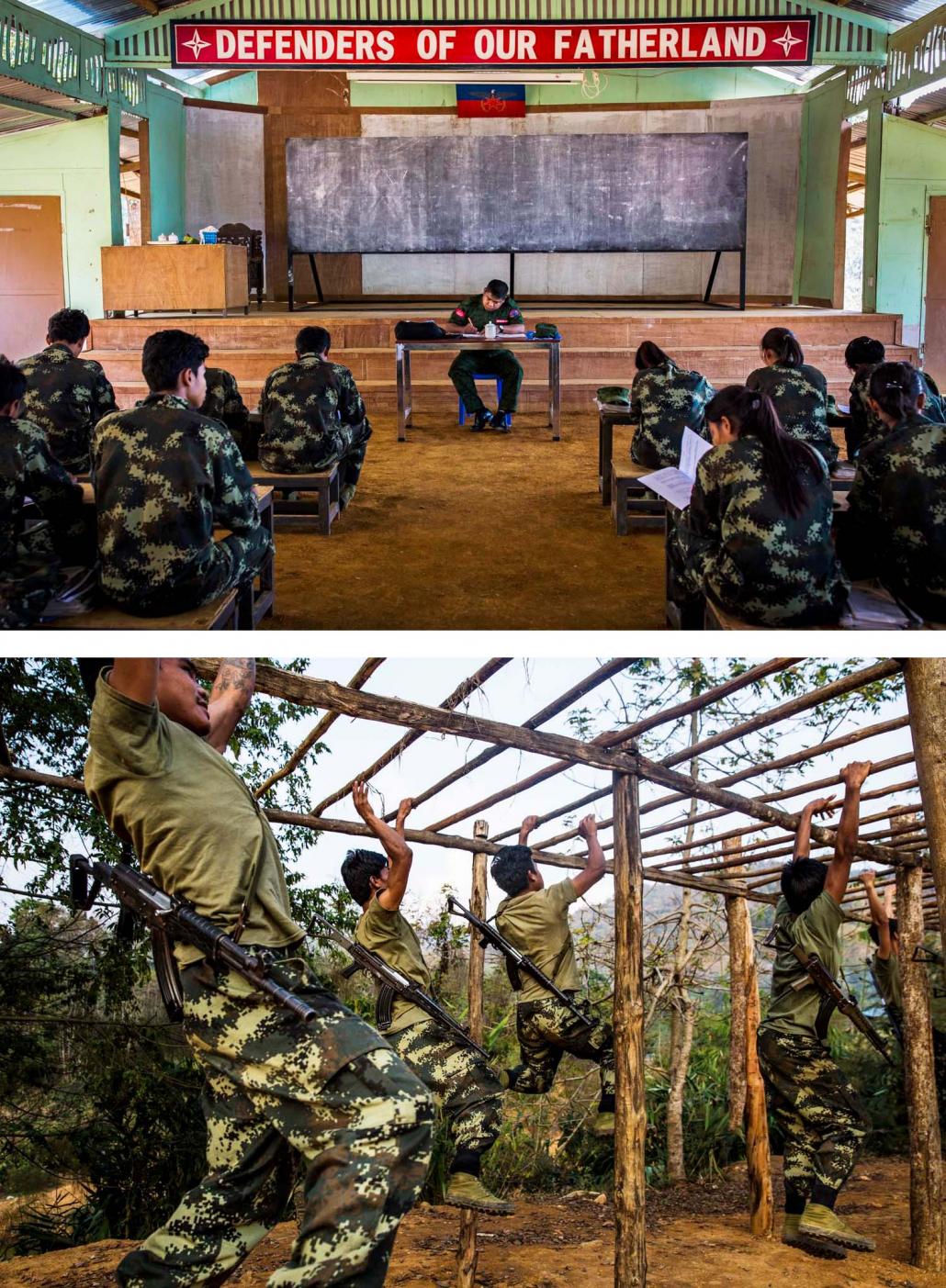

An Arakan Army training camp near Laiza. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

ARSA link denied

The AA denied government and military accusations after the Independence Day attacks that it had cooperated with the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, the militant group that attacked security posts in northern Rakhine in August 2017. The attacks were followed by a massive Tatmadaw operation that sent more than 700,000 people, most of them Rohingya Muslims, fleeing to safety in neighbouring Bangladesh.

Government spokesperson U Zaw Htay claimed in January that there were links between the AA and ARSA. Tatmadaw statements after the Independence Day attacks also claimed that the AA was cooperating with ARSA.

Although there were some similarities between the attacks, the allegations were strongly denied by the AA. Nyo Tun Aung said that unlike ARSA, the AA would never kill civilians, and pointed out the group had released soldiers and civilians detained during the attacks.

He said that the AA agreed with the government’s decision to brand ARSA as a terrorist group, despite the AA being labelled terrorists in turn by the government after the Independence Day raids.

“We are ready to cooperate with the military to crackdown on ARSA. We condemn terrorism; we will never cooperate with ARSA,” said Nyo Tun Aung.

The powerful Arakan National Party has also criticised the government and the Tatmadaw for claiming links between the AA and ARSA.

ANP general secretary U Tun Aung Kyaw said neither the military nor the government had provided any evidence to support a link between AA and ARSA. He said that if the allegation was designed to undermine support for the AA among ethnic Rakhine, he doubted it would work.

“Most Arakanese people support the AA; it is a fact,” he told Frontier.

Making the dream reality

Despite only being founded in 2009, the AA has emerged over the past three years as one of the country’s most prominent ethnic armed groups. The group enjoys considerable support because nationalist and anti-government sentiment is strong in Rakhine State.

It has a Rakhine nationalist agenda that includes self-determination, safe-guarding identity and cultural heritage and the development of the state, one of the country’s poorest.

The AA espouses what it calls “the way of Rakhita”, a rallying cry among Rakhine nationalists that evokes memories of the once powerful Arakan kingdom that was defeated by the Bamar Konbaung dynasty in 1784.

Another rallying cry is “Arakan Dream 2020”, in which it aims to achieve self-determination by the end of next year.

Nyo Tun Aung said the group envisioned a Rakhine State within Myanmar that had a significant degree of autonomy, citing the example of the territory managed by the United Wa State Army. At times during the interview Nyo Tun Aung referred to establishing an “Arakan kingdom”.

The AA has also built support in Rakhine State by shifting many of its forces there from Laiza, where it has been based since it was founded with support from the KIO.

Nyo Tun Aung said the group had even fulfilled its long-held dream of moving its headquarters to Rakhine State, but declined to reveal the new location.

“If I told you [the location], the military will go there; we are making a revolution,” he said.

The AA must remain in Rakhine because the Arakanese people need their own armed force, he said.

“If we do not achieve success in implementing our dream, the next generation should continue striving to implement it,” Nyo Tun Aung said.

The ANP’s Tun Aung Kyaw said peace and stability in Rakhine was more important than whether the AA had its headquarters there.

“We are very upset about the current situation; the fighting should be stopped,” he said.

U Than Soe Naing, a political analyst in Yangon, said the support of the Rakhine people was essential for the AA to achieve its goals, but he doubted whether armed struggle alone would be enough to secure autonomy.

“AA assumes that the Arakanese people supports them, and, actually, most of them do. I think that’s why the fighting has been so intense,” he said. “But I don’t think the AA’s ‘Arakan Dream’ strategy will bring change in Rakhine State.”

An Arakan Army drill near Laiza, Kachin State, close to the border with China, where the Arakan Army was established in 2009. (Hkun Lat | Frontier)

Fighting at Mrauk-U

The increasingly intense encounters between the AA and the Tatmadaw spread this month to Mrauk-U, the once resplendent capital of the rich Arakan Kingdom, which the government is planning to nominate for a UNESCO World Heritage listing in September.

Mrauk-U, about 60 kilometres north of the state capital, Sittwe, is famous for its Buddhist temples and stupas built between the 15th and 18th centuries, two of which were damaged by artillery fire on March 18.

The military and the AA have blamed each other for the incident; the AA also issued a statement with Northern Alliance members, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, which accused the Tatmadaw of committing war crimes in Mrauk-U.

The fighting in the ancient town has angered residents and raised concern among archaeologists, who say there is need to protect what are some of the country’s most important Buddhist monuments.

In a statement on March 18, the Myanmar Archaeology Association expressed extreme concern that the fighting could hinder progress towards the World Heritage listing of Mrauk-U.

“[Both armed groups] should declare Mrauk-U a demilitarised zone,” said the statement, which noted that Myanmar had in 1956 signed the 1954 Hague convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict.

U Thein Lwin, deputy director of the Department of Archaeology and Museum, said the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture would urge the president to use his powers to ensure that the temples are not damaged.

“It would be difficult to work on the World Heritage nomination if fighting continues there,” he said.

The fighting in and around Mrauk-U has displaced thousands of civilians, though the authorities have been slow to release figures. Estimates of the number of people displaced by fighting in Rakhine and Chin since late last year vary widely. The Rakhine State government recently referred to 7,800 IDPS but some estimates say about 20,000 people have been displaced.

The AA’s Nyo Tun Aung acknowledged that the Arakanese people would have to endure more suffering during what he described as the “storm of the revolutionary period”.

“The Arakanese people and the IDPs understand us,” he said. “We are very sorry for them.”

But Nyo Tun Aung gave no indication that the AA planned to pull back its forces.

“There will be more clashes in Rakhine,” he said.