A field guide to the Defence Services of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

Congratulations, recruit. You have volunteered – because the 2010 law allowing conscription is yet to be enacted – to be a member of the most important institution in Myanmar since colonial rule, even if it isn’t (officially) running the country.

We’re sure you will make Senior General Min Aung Hlaing proud. Any questions?

What is the Tatmadaw?

Probably should have asked that before enlisting, son. The Tatmadaw (which simply means “army”) is the nickname for the Defence Services of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar. It has a fully-equipped Army, Navy and Air Force.

The Army is by far the largest and most influential of the Defence Services and includes regional military commands, of which there are 14 throughout the nation

There are also several independent departments and a powerful business conglomerate, the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited.

How strong is the Tatmadaw?

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Stronger than ever, of course. You thought a little thing like democracy would make Myanmar weak?

In fact, this year parliament allocated more money than ever for defence – about K2.75 trillion (more than US$2 billion).

How much firepower does that buy? That’s hard to say. In fact, an Australian specialist the Tatmadaw, Dr Andrew Selth, once began a paper on the subject with: “Due mainly to the lack of reliable data, an accurate, detailed and nuanced assessment of Burma’s military capabilities is currently impossible.”

That said, most estimates put the number of active personnel at between 300,000 and 350,000, although the figure changes if you include paramilitary groups, reserve forces or the Myanmar Police Force (which may or may not be an arm of the military, depending on who you ask).

Some estimates are much higher. Data published in 2013 by the World Bank puts the number at 513,250 total active personnel, slightly more than Thailand.

The number of military personnel has not changed much in the last ten years, unlike the Tatmadaw’s technology and equipment. Myanmar sends engineers and pilots to Russia for technical training, which sends back weapons and vehicles.

Ukraine, Russia and China are favourite suppliers of tanks, armoured personnel carriers and artillery. The Interpreter, published by a think-tank in Sydney, has reported that since 2010 the Air Force has cut deals with Russia and China for scores of advanced attack helicopters, jet trainers and fighters. China has also delivered or signed contracts for new frigates and corvettes for the Navy.

The bottom line is that as well as total political control, the Tatmadaw also remains a significant force in Southeast Asia.

What kind of influence does the military have?

The writers of the 2008 Constitution certainly saw the need for the military’s strong hand in politics. It lists “enabling the Defence Services to be able to participate in the National political leadership role of the state”, as one of the basic principles of the Union.

The chapter in the constitution on the Defence Services is only one page long, leaving its specific powers and responsibilities largely to parliament, over which the army has considerable sway.

A quarter of all parliamentary seats in Myanmar, including 56 upper house seats and 110 lower house seats in the Union hluttaw, are reserved for military appointees. This gives the military bloc an effective veto over amendments to the constitution, which require the support of 75 percent of MPs.

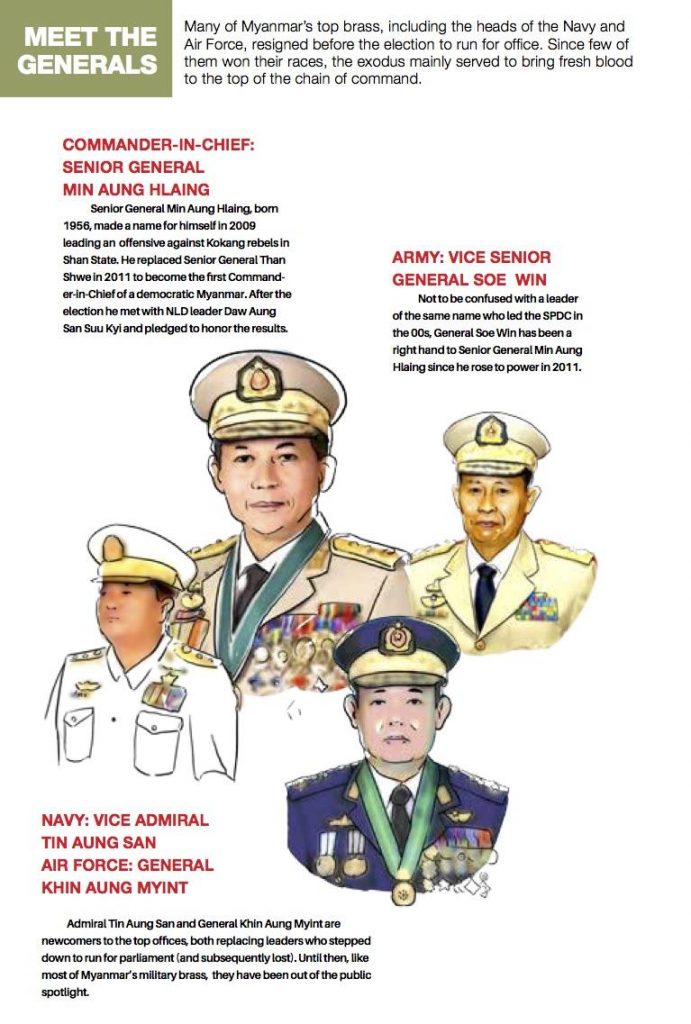

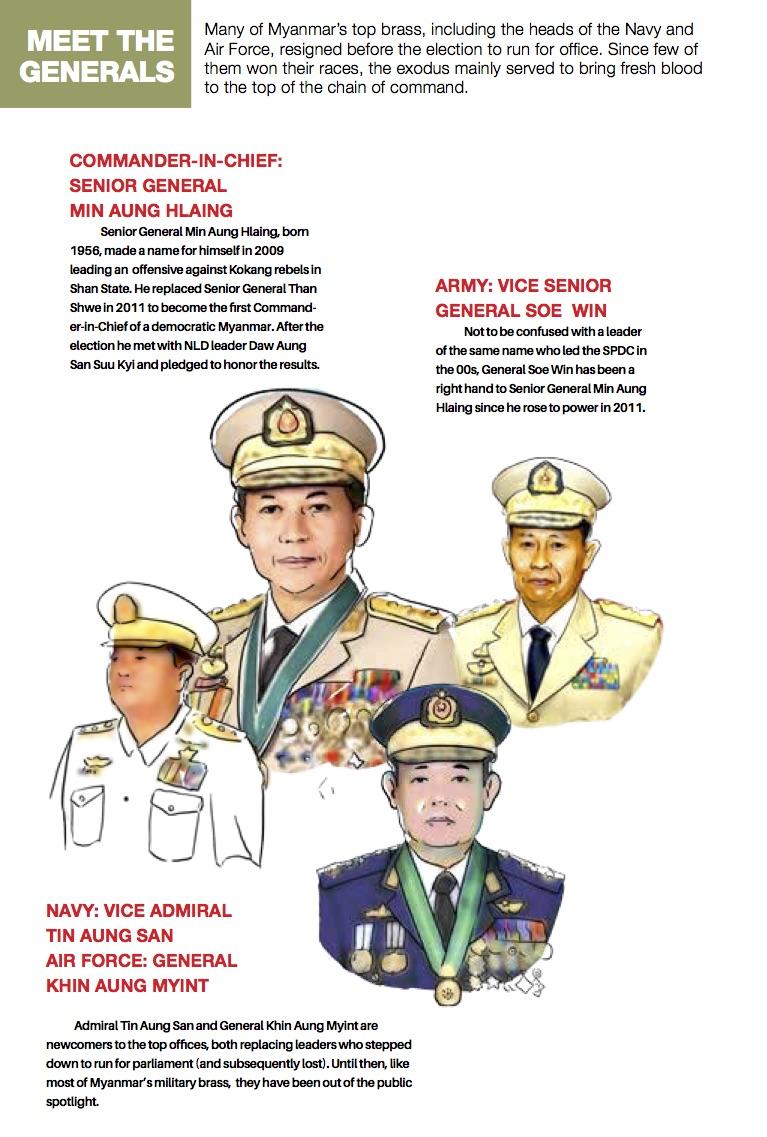

Many of Myanmar’s top brass, including the heads of the Navy and Air Force, resigned before the 2010 election to run for office. Since few of them won their races, the exodus mainly served to bring fresh blood to the top of the chain of command.

The military bloc in June exercised its veto to thwart an amendment that would have reduced the threshold to 70 percent, but such a show of force was rare. The military has been relatively ambivalent towards legislation that that does not affect it.

In lieu of an order, military MPs may vote as they wish, if they vote at all, and some do not have a favourable opinion of elected MPs. According to a briefing by the International Crisis Group: “Legislators from the armed forces have stated and hinted during debates that their elected counterparts are ‘undisciplined’, chewing betel in the building and arriving late for sessions.”

Does the military do business?

Very much so. The Tatmadaw-run Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited has stakes in such ventures as Myanmar Brewery, Pansodan Bus Lines and the controversial Letpadaung copper mine.

Does it still spy on people?

That is perhaps not a wise question for a new recruit to be asking.

The former Military Intelligence organisation was notorious for its vast spy network and shadowy operations. In 2004, MI chief and Prime Minister General Khin Nyunt was arrested on corruption charges amid dramatic circumstances that led to a purge of the organisation and the jailing of many of its officers. Most have since been released under amnesty.

The Tatmadaw’s current intelligence arm, headed by chief of Military Security Affairs Lieutenant-General Mya Tun Oo, is a shadow of the old MI. Supposedly.

Myanmar’s military is larger than those of both Thailand and Bangladesh, despite the country’s smaller population.

What is it like being a soldier?

Three years of honourable and glorious service to your country. Of course, you’ll only be paid about US$150 a month, but then again soldiering in Myanmar has never had a glamorous reputation.

“The life in the military is very rough, everybody knows,” said U Wai Linn, who spent 19 years in the army, ultimately retiring from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2005. Even so: “I enjoyed my life in the army.”

Like most young men, he said, it wasn’t the prospect of power or money that made him enlist, but the experience, adventure and romantic allure of army life. “I remember in my childhood, the soldiers marching in the parade, their uniforms, the music. That’s why I wanted to join the army.”

Quick facts

Manpower: 300,000-350,000 active

Males fit for military service: 10,451,515

Females fit for military service: 11,181,537

Conscription: Allowed by 2010 law (yet to be enacted)

Service term: 3 years

Soldier salary: Roughly US$150/month

Defence spending: 3.7% GDP (official)