Blockbuster political thriller Responsible Citizen has left audiences astounded at the lenience shown by the film censorship board, but its director is not expecting any prizes from the Myanmar Motion Picture Academy.

By MYINT MYAT THU | FRONTIER

MYANMAR-INDIAN director Steel’s political film, Responsible Citizen, which was released in August, was not only a commercial success but also revealed a new, more lenient side of the notorious motion picture censorship board. Its overwhelming success – based on ticket sales and the many positive comments that appeared on Facebook after its release – is evidence that Myanmar audiences have long been waiting to see their common villains depicted accurately on the big screen.

There is nothing special about the style of Responsible Citizen, but the story it tells is an unapologetic portrayal of corruption and bribery. In its classic tale of hero versus villain, a patriotic police officer has to walk an outlaw’s path to recalibrate the moral compass of a world wrecked by crooked ministers and tycoons. The film’s message is that anyone can be a responsible citizen by waging war against wrongdoers.

At a time when filmmaker Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi is serving a one year jail sentence with hard labour for satirical Facebook posts about the Tatmadaw, the incendiary dialogue in Responsible Citizen resonates powerfully. “We want to demolish old cinemas in downtown Yangon and replace them with hotels. Help us to gain approval and 20 percent of the project is for you,” a crony tells a minister in the film.

In Myanmar, political movies have long been deployed for the purposes of military propaganda. Big-budget, star-studded army movies were once a staple of Tatmadaw-owned Myawaddy TV, but struggled to attract audiences as new TV channels began to emerge over the past decade.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

Responsible Citizen punches above its weight to shake up the genre of political cinema. It has resonated with audiences in part because its release has coincided with public outrage about an incompetent investigation of a major rape case and low levels of faith in politicians.

Some viewers have observed that the movie seems to be more of a collection of vignettes based on actual incidents rather than the director’s imagination.

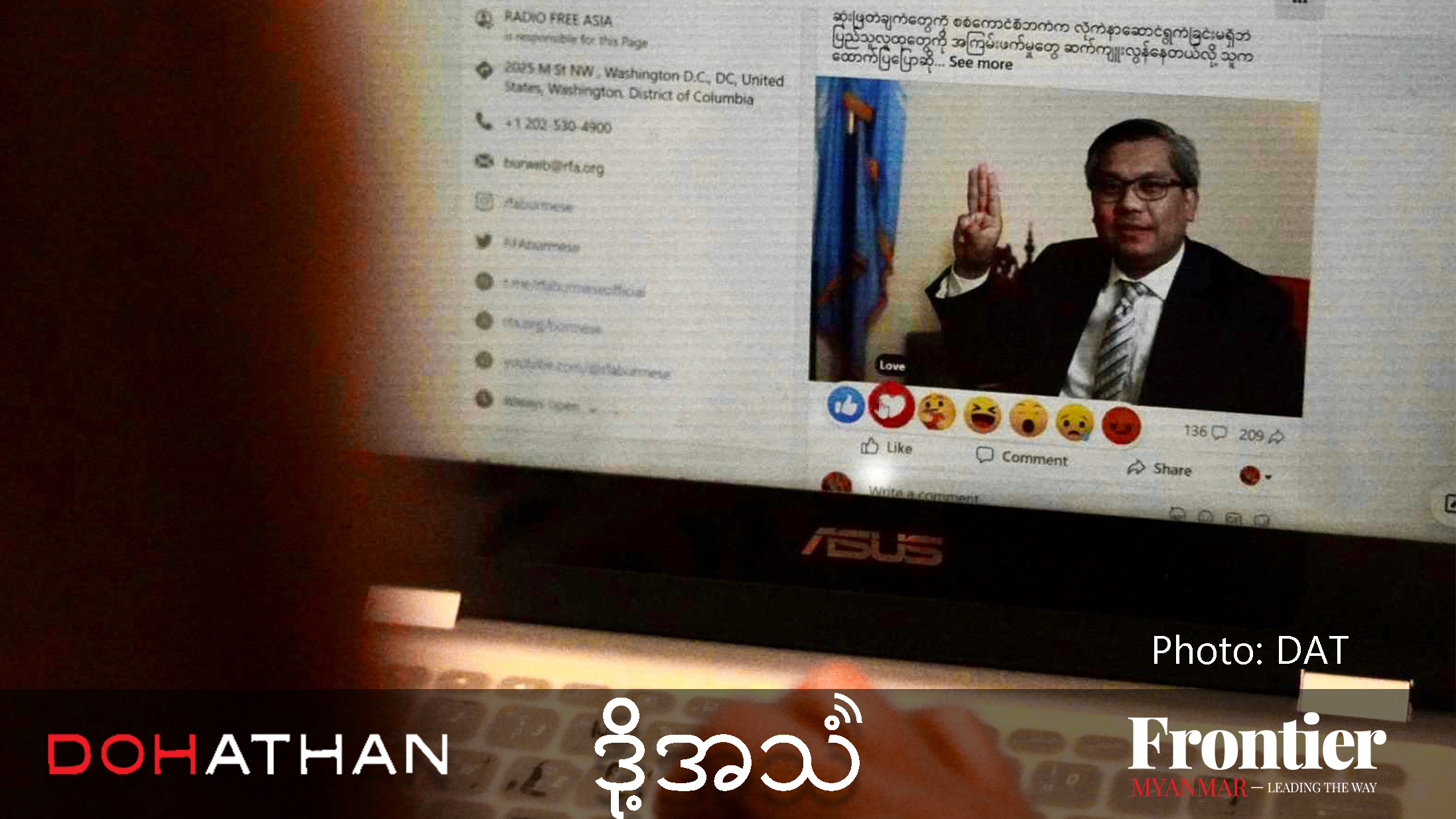

11.jpg

A scene from Responsible Citizen, a new film from director Steel. (Supplied)

There is the rape and murder of a supermodel by the sinister sons of ministers, one of whom is named Kaung Tayza, and the untouchable status they enjoy that enables them to revel in drug abuse; the torturing of an outspoken farmer by a minister at a political rally; examples of the monopolies enjoyed by cronies; and images depicting a crumbling judicial system in the hands of a few powerful men.

“I had to create imaginary characters in imaginary situations because of censorship, and for my own safety, but I’m not imagining really,” the film’s director, Steel, told Frontier. “For example, in Myanmar you just can’t show how bloody long it takes to get anything done at a government office. We all know this is the truth in Myanmar, but the time to show it in cinema has yet to come.”

Steel’s father was a police officer and the filmmaker said he grew up in Yangon trained to believe that everything should be done by the book. In his ideal film, the corrupt ministers’ evil sons would have been arrested on suspicion of having killed the supermodel and be thrown into a police van. But Steel said he was afraid that this ending would have fallen foul of the censors, so he had to find another, indirect way to bring them to justice.

Yet, Responsible Citizen seems to have received remarkably favourable treatment from the censors overall, particularly considering the film’s outspoken message and how petty the censors tend to be. Filmmakers in Myanmar are still required to submit their script for approval before production can begin, and the film is reviewed again once it is shot. Many who went to watch Responsible Citizen were left wondering how it managed to get through the censorship process.

Ko Zin Ko Ko, a film critic who publishes reviews online, described Responsible Citizen as “amazing” and said it was a direct challenge to those directors who claim that because of censorship they can only make cheap comedies often referred to as paw kar, or “silly movies”.

“After seeing Responsible Citizen, I really wondered if what they [other directors] said was the truth or just an excuse” to justify the poor quality of their movies, he said.

hkl08672.jpg

Director Steel said he had to create imaginary characters because of censorship. (Hkun Li | Frontier)

Neither Steel nor censorship board members would discuss which, if any, scenes were cut for the final version of Responsible Citizen. But it seems clear that the censorship process is much more fluid and open to negotiation than many people probably realise.

Steel said that patience was important when dealing with the censors. He said he submitted a “more elaborate” script than is usually required and when he decided to make changes during production, he informed the censors about them. Despite these precautions, he was still prepared for a standoff because of the film’s content. “Since the start of the film we said this story was fictional, but the censors considered most of the parts could directly or indirectly defame a particular person,” he said.

Steel said it helped that he was “prepared to make changes when he was wrong” – an apparent reference to complying with censorship requests – while at the same time being prepared to speak out, albeit very politely, when he believed he was right. “Honestly, I still cannot get a clear picture about censorship,” Steel said. “I just had to use all the interpersonal skills I have to bring the film into life.”

Censorship board member Daw Grace Swe Zin Htaik, a Myanmar Motion Picture Academy Award-winning actress, agreed that some of the dialogue in Responsible Citizen was savage but she said she decided to allow it if it was relevant to the film’s intentions. She claimed that the censorship board wanted to help filmmakers make better movies. “When we give them any guidelines, it is just to suggest to them how they can show what they want to show,” she said. “Even in the censorship board, the voices are not uniform; there can be four or five tones among us.”

Another censorship board member, prominent filmmaker U Myint Thein Pe, agreed that the censorship process was a negotiation. He said that if filmmakers made more effort to explain their creative decisions to the censorship board, their films were much more likely to be approved.

“In some cases, we allow them if they can make strong points to justify their decisions,” he said.

“We give them more freedom from censorship these days, but we can’t help them if they do not make use of it,” he said. “And there are so many stories that they can tell without needing to challenge the censorship [process]. I believe they just don’t make them.”

17.jpg

A scene from Responsible Citizen, a new film from director Steel. (Supplied)

Responsible Citizen would seem to be a solid candidate to win at least a few Myanmar Motion Picture Academy Awards. Steel though has mixed feelings about the film’s chances of success. “I sometimes hope that my work will be recognised but I know this [an academy award] is not something I should expect. It is just not for me,” he said.

Past experience suggests a filmmaker of South Asian descent is unlikely to be recognised. Steel said his friends often told him he would always be an academy award outsider because his complexion was too dark to stand on the stage with a trophy.

“I don’t know how the selection process works or if it is in sync with the audiences,” said Steel, who also goes by the name Ko Sar Mi. “In my case, being black, my race will have a lot to say. I never have seen [a director of Indian descent] win an academy award in Myanmar.”

Just getting to the big night can be a challenge. When he got his first screenwriter credit back in 2000, for the film One Dream for Two, his name was mysteriously left off the guest list for the academy awards ceremony. Steel said the MMPO blamed the film’s production company, but when he sought further explanation he was ignored.

Some even question whether a Myanmar-Indian director is entitled to make a political film.

“Some people asked me if a kalar can have anything to do with politics,” said Steel, using a derogatory term for a person of South Asian descent. “What I am doing is not politics and I don’t fully understand the current politics of Myanmar; but I would say I am politically aware and active.”

Unconcerned by this criticism, Steel is already working on the script for his next political film, My Country.

In Responsible Citizen, he gave Myanmar audiences a much-awaited hero and reminded them that there can sometimes be little difference between political leaders and criminals. We will have to wait and see who will be the heroes and villains in My Country.