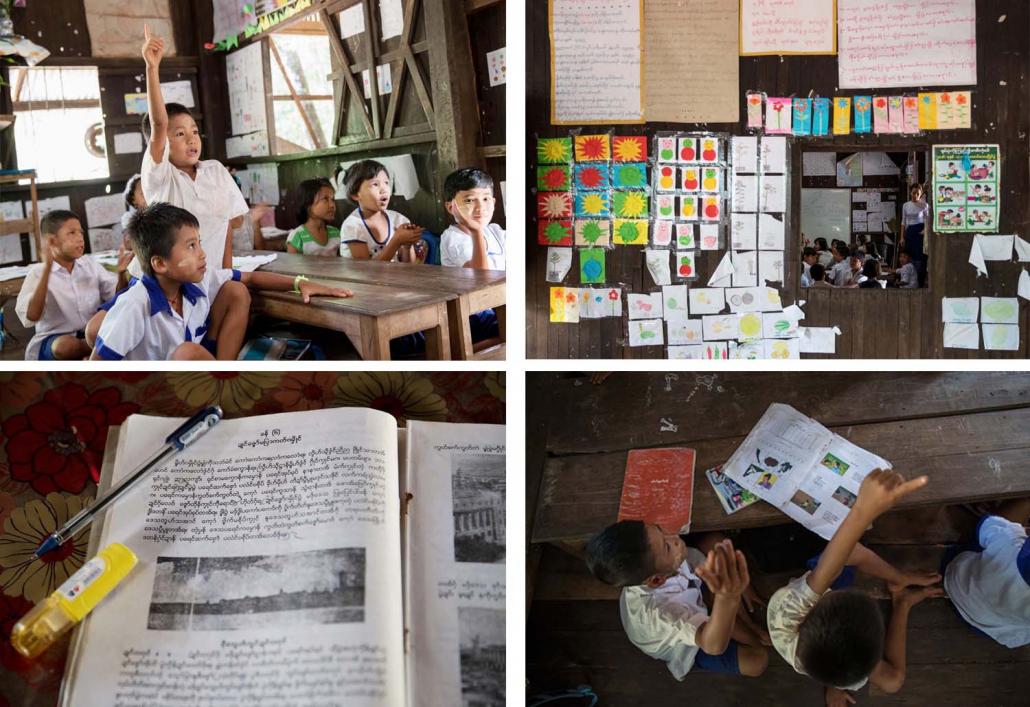

The government and ethnic groups in revolt against it have run parallel education systems for decades. Mon educators now seek recognition for their mother tongue-based system, while the government slowly brings ethnic languages into classrooms.

By EVA HIRSCHI | FRONTIER

Photos NYEIN SU WAI KYAW SOE

WHEN MI SAR Yar Poine was growing up in Mon State, there were few opportunities to learn her mother tongue.

“When I went to the governmental primary school, everything was in Burmese. Only during holidays, when we went to monasteries, were we able to learn Mon,” said Sar Yar Poine, project coordinator at the Mon Women’s Organization.

“Of course it is important to learn Burmese, too,” she said, referring to the official language of Myanmar, which is the language of the Bamar, or Burmans, Myanmar’s dominant ethnic group, which comprises an estimated two-thirds of the population.

However, when speaking Mon at home, Sar Yar Poine sometimes encountered gaps in her vocabulary that she could only fill with Burmese words learned at school. The same dilemma in reverse occurred at school, where it was often hard for her to follow teachers talking in Burmese.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

“I think a multilingual education is very important,” she told Frontier.

Although more than 100 languages and dialects are spoken throughout Myanmar, Burmese is the country’s only official language; it is the sole language of instruction in schools, and the only language sanctioned for use in government administration, the law courts and mainstream politics.

The high drop-out rates in schools in ethnic minority and rural areas are considered partial evidence that teaching only in Burmese is an obstacle to an education for some children.

“It is important for children to be educated in a language they understand,” Min Aung Zay, head of the Mon National Education Committee, told Frontier. Studies have shown that children from ethnic minorities learn better if they start their education in their mother tongue and gradually switch to learning in the national language.

But former military governments – closely identified with the Bamar majority – restricted the teaching of ethnic languages in schools because they believed it might encourage separatism. Meanwhile, grievances over the language of education are among a complex set of factors that have driven ethnic revolt since independence in 1948.

Parallel education systems

Civil conflicts, which mainly occur in non-Bamar areas, directly affected education because they often resulted in the closure of government schools or the inability to open new ones. To fill the gap, some ethnic armed groups established their own schools and ethnic civil society groups developed curricula that enabled children to be taught in their mother tongue, rather than Burmese.

Reflecting an awareness of the role of language in identity-building, the development of separate education regimes was one of the strategies used by different ethnic groups to resist “Burmanisation” and preserve their languages and culture. It was also a demonstration of opposition to military rule. As well as mother tongue teaching, the curricula in ethnic schools often differed sharply in their content and messages from those used in government schools, for instance in their presentation of history.

For many years, the two education systems and their values seemed locked on different paths. However, the inclusion of ethnic nationality languages in government schools has been gathering pace since democratic reforms began in 2011.

The teaching of ethnic languages was gradually introduced to schools, but with lessons taking place outside of official school hours. There has been slight but measurable progress since then, with the hiring of fulltime, mother tongue-speaking teaching assistants and the drawing up of local curricula for different ethnic states.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

The Mon as pioneers

Several ethnic armed groups have established their own education departments, of highly varying degrees of development and differentiation from Myanmar government models.

The Mon have one of the country’s oldest ethnic education systems and it is often cited as an example of best practice. The Mon, who are native to southeastern Myanmar and once ruled over a large portion of the country’s south, speak an Austroasiatic language that differs substantially from Burmese, which is a Sino-Tibetan language, and are credited with the early spread of Buddhism in the territory.

The New Mon State Party, which fought the Tatmadaw for decades before signing a ceasefire in 1995, began opening mother tongue schools in areas under its control in the late 1960s. In 1972, the NMSP established an education department to administer the schools, in which all classes were taught in Mon.

In 1992, the NMSP established the Mon National Education Committee to administer the schools and after the 1995 ceasefire, the MNEC expanded the schools to areas where territory held by the NMSP and the Tatmadaw overlapped.

“We teach all subjects in Mon language, except science and Burmese language classes,” said Mi Nondal Davy, director of the Mon National Primary School established in 1996 at Naing Hlon in Mon State’s Mudon Township. Almost all of the textbooks and educational materials at the school are in Mon.

Schools administered by MNEC encourage multilinguism by using Mon as a language of instruction in primary school, transitioning to Burmese in middle school and using Burmese as the main language during high school, while continuing with mother tongue classes. MNEC’s curriculum, however, is similar to that used by the government and students are able to subsequently attend government universities.

The main difference between the two curricula is the extra modules for ethnic history and culture, which are not available at government schools. “For us, it is important to teach the children not only the Mon language, but also Mon history and culture,” Nondal Davy told Frontier.

In government schools, history lessons reflect a Bamar perspective, which is often antagonistic to that of ethnic minorities. “For now, our heroes are their enemies and vice versa; we need to change the curriculum together and use a more neutral approach,” Nondal Davy said regarding any future convergence between the Mon and government systems.

The children of other ethnic groups are not served as well as the Mon. While Mon schools have their own textbooks, other non-state, ethnic-administered schools rely on translations of government textbooks, which do not accurately reflect the culture and history of the ethnic group in question.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

Few teachers, low salaries

Non-state ethnic schools have received some support from international organisations, such as the United Nations children’s fund, UNICEF. “Using a conflict sensitive lens, UNICEF is supporting ethnic language development as a means of conflict resolution,” said UNICEF education officer U Thet Naing. “We support a system that will contribute to promoting equity in education.”

However, mother tongue schools suffer from a lack of qualified teachers and funding to employ them. The Mon National Primary School at Naing Hlon employs five teachers, who each graduated in different disciplines. They have undergone one- to three-month teacher training courses conducted by the MNEC, because government universities don’t provide suitable courses.

Low salaries are another deterrent: mother tongue teachers at non-state, ethnic-administered schools are sometimes paid as little as K30,000 a month, much lower than their counterparts at government schools.

Teachers at government schools are paid between K150,000 and K180,000 a month, depending on the grades they teach. They are also paid all year, unlike teachers at the non-state schools, who are usually only paid for the months they work. This means they do not receive a salary for the annual hot season break of about two to three months.

“Last year, we paid regular teachers at our schools a salary of K94,000 a month, which is substantially more than in past years, when salaries sometimes have been as low as K40,000 a month,” said Nondal Davy. The increase was made possible by a rise in donations for the Mon schools, which are funded by MNEC but rely heavily on financial support from Mon monks, Mon civil society groups and community members. “We don’t receive any financial support from the government,” said Nondal Davy.

Education for peace

MNEC is drafting a Mon education policy that it intends to submit to the government in the coming months and which seeks recognition and funding. Work on drafting the policy began in May 2016 and has included trips to consult different Mon communities and civil society groups to formulate common goals. MNEC has also consulted with members of other ethnic groups and participated in inter-ethnic seminars.

“We hope to make the first step, but the long-term goal is to have ethnic education, not only ethnic language classes, for all ethnicities,” said Mi Hlaing Non, a project coordinator at MNEC.

She believes that mother tongue education as well as classes in ethnic culture and history will contribute to peace and national prosperity. “In the new curriculum, we also want to include goals such as how to live together in peace,” Hlaing Non told Frontier.

Although there’s broad agreement among stakeholders about the need to teach children Burmese, the right to mother tongue education is a longstanding demand of ethnic armed groups. The UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report issued annually since 2002 recognises the role of education in contributing to conflict, but also to peace building. An important factor is the acceptance and use of minority languages in schools.

Chapter six of the 2015 Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement, which has so far been signed by the Tatmadaw and 10 ethnic armed groups, says that the governing authority of ethnic armed groups should be respected in such matters as health, security, resources management and education in the areas that they control.

Despite this, “education issues have not been much discussed in the current peace process,” said Dr Ashley South, a research fellow at Chiang Mai University whose work specialises in ethnic conflict and education policy in Myanmar.

The relationship between government and non-state ethnic education systems in Myanmar still awaits serious discussion. There is currently little consensus over whether they should remain as separate, parallel systems, or begin moving together under a process of “convergence” – and if so, at what pace. However, there will be little for government institutions to converge with if non-state systems aren’t supported.

“Ethnic education systems in Myanmar provide locally owned and delivered, multi-lingual or mother tongue-based education to among the most vulnerable and marginalised children,” South told Frontier. “It is important to support these systems during the probably lengthy period of transition from a centralised and military-controlled system, towards an education system which respects and welcomes ethnic nationality cultures and languages, reflecting Myanmar’s ethnolinguistic diversity.”

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

Small steps

Although education has so far not been directly addressed as part of the peace process, government support for certain aspects of mother tongue education is slowly increasing, as previously discussed in the Frontier article “Ethnic language teaching’s decentralisation dividend” by researchers Nicolas Salem-Gervais and Mael Raynaud.

Article 44 of the 2014 National Education Law allows for regional and state governments to establish the teaching of ethnic languages and literature “starting at the primary level” before “gradually expanding” to higher grades. Article 43, introduced via a 2015 amendment to the law, permits ethnic languages to be used alongside Burmese as a “classroom language”.

To implement the latter, the Department of Basic Education has created a position for “teaching assistants”. These assistants are to be on hand to explain the contents of the Burmese-language curriculum to ethnic students in their mother tongue. The government hopes, in this way, to raise learning efficiency and reduce dropout rates.

In September last year, the ministries of Education and of Ethnic Affairs called for applications to fill positions for the teaching assistants. Successful applicants will receive at the least the legal minimum wage of K4,800 a day, amounting to considerably better pay than the K30,000 a month that ethnic language teachers are currently paid to teach after-hours classes in government schools.

In January, 5,161 mother tongue language teachers were appointed as teaching assistants at Basic Education Schools, figures from the Department of Ethnic Literature and Culture showed.

Another notable reform is contained in Article 39(g) of the education law, which says, “there shall be freedom to develop the curriculum in each region”.

Since 2018, the education ministry and the state governments of Chin, Mon, Kayin, Kayah and Kachin, with support from UNICEF, began developing state-specific curricula that will be taught from the 2019-2020 school year in five out of the 35 periods in a primary school week. Three of these five periods will be for the teaching of ethnic languages, with textbooks developed by literature and culture committees; the other two periods will be dedicated to the geography, history and culture of the given state. Shan and Rakhine states, and some Bamar-majority regions, are expected to follow.

Nyein Su Wai Kyaw Soe | Frontier

Negotiating diversity

Another challenge for mother tongue teaching is that ethnic communities in Myanmar are rarely homogenous in terms of language. The pioneering role of the Mon education system was enabled by the relative uniformity of the Mon language. However, for the Karen, who speak at least 12 different dialects that are mostly not mutually intelligible, there isn’t a mother tongue-based system that caters to the diversity of the community.

South said that determining which ethnic languages should be used in which regions could potentially lead to new conflicts – not least because, on top of the variation of language and culture within ethnic communities, many share their homelands with other ethnic groups.

“Which subjects to teach in schools and communities with more than one ethnic nationality should be the subject of discussions and consultations,” he said.

He said of the local curriculum initiative being undertaken in some states, “This initiative is at an early stage, but constitutes an important step in the right direction.” However, he stressed that “this is not yet mother tongue-based schooling, which would require ethnic nationality children to use their first language throughout most of primary school”.

South says the discussion about ethnic education is an important element of the peace process.

The political negotiations that are supposed to result in a Union Peace Accord are currently deadlocked, prompting several of the ethnic armed groups that have signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement to lose confidence in the process.

“If the government could demonstrate to ethnic nationality communities that the peace process can result in federalism, including local control of important services such as education, this would do much to build confidence and trust in a faltering peace process,” he said.