Myanmar’s banking system has barely functioned since tens of thousands of private sector workers walked off the job three weeks ago in an effort to pressure the military to give up power, crippling large sections of the economy.

By FRONTIER

Each day since February 7, Ma Nwe Nwe Aye has done exactly the same thing: protest outside the Central Bank of Myanmar branch in Yangon’s Yankin Township.

She holds a placard urging its workers to join the Civil Disobedience Movement, the campaign launched shortly after the February 1 coup that encourages civil servants and some private sector workers to refuse to work under the junta.

Nwe Nwe Aye believes that the fastest, most efficient way to force the military to give up power is to bring the country’s financial machinery to a halt. If the economy seizes up, the Tatmadaw will eventually run out of money, she figures.

“The Central Bank is key to cash flow in Myanmar, so whether or not its staff join the CDM will have a big impact on the success of the revolution,” she told Frontier on February 22, the 16th consecutive day she had protested outside the bank. “If all Central Bank staff join CDM, the coup will fail – I believe that.”

The focus on the CBM – and the banking sector more broadly – seems to have rattled the military. When Nwe Nwe Aye and other protesters arrived at the bank on February 15, they were confronted by armoured personnel carriers and trucks full of soldiers from the Light Infantry Division 77, an elite until that has been accused of human rights violations.

If this was designed to intimidate, it didn’t work; after a brief stand-off, Nwe Nwe Aye and the other protesters simply moved their demonstration slightly further down the road. The same day, police went to a housing complex in Thingangyun Township to try to force around 200 CBM staff to return to work, but were turned back by protesters.

The junta’s financial headaches extend far beyond the CBM. In the private sector, tens of thousands of bank staff are refusing to work and many have joined the CDM, which was launched on February 3 to protest the military coup. With no workers available, most of the country’s 2,000 private bank branches have been forced to close since February 8.

Many striking bank staff have joined the Myanmar Bankers Union, which set up a Facebook page on February 3 and has been staging regular protests of between 500 and 1,000 bank workers, mostly through downtown Yangon.

Founder Ko Bo Bo, 29, estimates that more than 6,000 workers from the banking sector have formally joined the CDM, including from state and military-owned banks. Many more are also refusing to work. “We have to join the CDM because we can’t run the machinery for the dictators,” he said. “I urge remaining private and government employees to join us in this revolution for a better future.”

‘Back to the Stone Age’

The closure of the country’s bank branches has now left most account-holders without access to funds for three weeks. Businesses and individuals have been forced into a mad scramble to access alternative sources of cash, particularly as payday approaches at the end of February.

The shutdown has also hit many exporters and importers, who have largely been unable to send and receive payments. The government, too, has been hurt; when it sought to sell K200 billion of five-year Treasury Bonds on February 15, it received just one bid, for K1.7 billion, at a higher-than-normal interest rate of 9.0pc. Transactions between banks have been brought to a standstill.

“I never imagined I’d see anything like this,” said one senior official from a smaller private bank, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “It’s like we’ve gone back to the Stone Age. People are trying to keep hard cash so they can settle payments, because the payment system has almost totally stopped.”

Although some online transactions are still possible, this has been of only limited use in Myanmar, where digital banking remains in its infancy. Many transactions can still only be carried out in a branch, including even basic tasks such as transferring funds to an account at another bank.

Even transactions that would appear to be automated have been affected – for example, incoming foreign transfers. Although the money is coming into the bank, staff are needed to direct the funds into the receiving account. “We’re facing many difficulties to operate bank services,” said a senior official from a mid-sized bank. “For example, we can’t do international bank transfers mainly due to a lack of staff.”

The lack of international transactions has raised concerns about Myanmar’s ability to continue importing essential commodities, such as refined fuel and palm oil. Reflecting this concern, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing spoke at a February 25 meeting of the need to reduce fuel and cooking oil imports to address trade imbalances.

“There are huge difficulties with international payments. For example, rice exporters don’t know their payments have arrived – the money might have been sent by the buyer but it’s not in their account,” said Dr Soe Htun, a prominent businessperson who is heavily involved in imports and exports. “And how can we import things if we can’t transfer money? If there’s a shortage of fuel, every sector of the economy will suffer.”

With Myanmar still largely a cash-based society, money in an account often needs to be withdrawn as cash to pay suppliers or employees, or cover running costs. ATMs are still operating to some extent, providing some relief to individuals, but demand for withdrawals is far outstripping supply. Some businesses have turned to moneychangers for access to cash in foreign accounts, using them to remit money informally from abroad.

“Right now we can’t spend a single kyat unnecessarily,” said a senior executive from a foreign firm that has multiple investments in Myanmar. “Our first priority is to use our reserves for staff salaries. The second priority is emergency expenditures – that’s it. If we’re very careful, we might be able to last another month.”

Another businessperson said they had paid their staff’s February salaries using electronic transfers as usual, but it wasn’t clear whether employees would be able to withdraw the money from an ATM. “Yangon isn’t like Singapore, there aren’t ATMs everywhere … it’s first come, first served – if you get lucky you can withdraw money,” they said.

Given how reliant Myanmar is on cash, the shutdown of bank branches has the potential to cripple the economy and cause a financial crisis.

This is exactly what protesters and boycotting staff are betting on – they figure the shutdown will show the military the impossibility of trying to govern in the face of such widespread public opposition to its rule.

“If all banks are shut down, it will have a huge impact on the country’s economy,” said Bo Bo, the MBU founder. “But it will hurt the regime too because without the banking system, they will struggle to pay employees or run state enterprises.”

There’s little sign of the military’s resolve weakening yet, but it also doesn’t seem to have any answers to the banking crisis. Speaking to Frontier on February 11, new deputy governor U Win Thaw said the Central Bank has prepared plans to ensure the banking system is able to function even if the protests continue, though he declined to offer details.

“We have plans A, B and C to ensure that the financial system does not come to a halt. If plan A doesn’t work, we will use plan B, and if it doesn’t work, there is plan C,” he said. “But I can’t tell you what those plans are right now.”

Industry insiders say the regime has made various threats to bankers in an effort to force them to reopen branches, but the Central Bank and some private bank officials dispute this, saying there has been no pressure. “It’s not true that we are going to take action, we just told them verbally to try to offer services to their customers,” Win Thaw said.

Regardless, private banks can hardly force their staff back to work – something even the regime has been unable to do with the Central Bank workers who have joined CDM.

“The protesters are focusing like a laser beam on an obvious weakness for the military, and it doesn’t seem to have any idea how to respond,” said one business source. “The generals don’t seem to realise that this isn’t 2007 anymore.”

Public pressure

Unlike a decade or two ago, private banks are today more afraid of the public than the military.

With the people so united against military rule, any bank seen as toeing the Tatmadaw’s line is likely to be punished – including, potentially, by a flight of deposits that could cripple the institution.

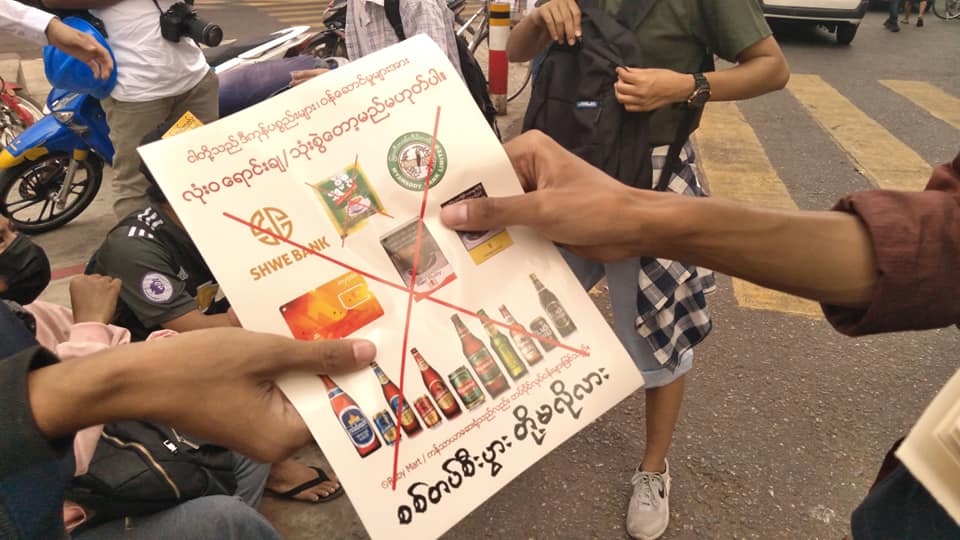

The MBU has already urged the public to no longer use state-owned Nay Pyi Taw Development Bank, after it allegedly fired employees who had protested against the military. Activists also called for a boycott of Shwe Bank, which is part of the Shwe Than Lwin conglomerate, because of its perceived close relationship with the Tatmadaw. On February 18, the bank was forced to issue a statement saying it had no affiliation with the military and that it was not pressuring staff to return to work. It had told its employees they could act as they wished – an apparent endorsement of their right to protest against the military – and would still receive their full benefits.

Meanwhile, KBZ Bank has come under fire after a recording leaked online in which the bank’s deputy chief executive officer, U Aung Kyaw Myo, apparently urged branch managers to quietly reopen the “back door” of branches for the bank’s larger customers. When some on the call expressed concern that they might face a backlash from the public and their neighbours, Aung Kyaw Myo replied, “Just pretend as if you are joining the protests and then come to the bank quietly.”

A senior official at KBZ confirmed the authenticity of the recording and told Frontier that some middle managers and “elders” in the bank had reopened branches and conducted transactions without the knowledge of the CEO.

But two KBZ staffers, including one who has joined CDM and another who has not, said the only activities taking place at their branches were the filling of ATMs. “Although we are on CDM, we agreed with our manager to help fill the ATMs with a roster system so that people can access their money,” said one staffer. “We will keep doing CDM until the elected government comes back. Right now we are not thinking about our salary.”

On February 25, KBZ sent a notice to staff informing them it planned to open branches for limited transactions from March 3 to 5 and invited those who are willing to work on those days. It also said there would be “limited” services for customers, but did not provide details.

The senior official from the small private bank said it was difficult to even go to the bank headquarters in the current environment. “We are facing a lot of pressure. There are a lot of people pleading with us not to run the bank,” he said.

The bank is running on what he described as a “limited system”, with perhaps a single branch quietly open for appointments only. “We have a contractual relationship with our clients – if they want their money, we have to give it to them. So we try to give service but in a very limited and, unfortunately, a very untransparent way … at the same time we pray there will be a resolution to this crisis.”

He said the episode had been a “big learning lesson” for Myanmar’s bankers. “In the past, we just tried to please the regulators and customers,” he said. “Now the public are stakeholders, too.”

Back to normal?

Despite these challenges, there have been indications this week that activity in the banking sector is increasing.

Every day, the Central Bank publishes data on interbank foreign exchange trading, including both interbank dealing and bank-customer dealing. In January, customer dealing averaged close to $70 million a day, while bank dealing was about $20 million a day.

From February 8, when private bank staff joined CDM, levels of both customer and interbank dealing crashed, with almost no trade taking place over the next two weeks.

But on February 22, activity began to pick up again, and customer dealing has averaged about $12.3 million and interbank dealing $4.5 million per day. Although this is barely one-fifth of the January average, Win Thaw was quick to trumpet it as a return to “nearly normal”.

He said banks had been able to resume interbank transactions, the interbank foreign exchange market, and international payments for importers and exporters because protests had diminished since large demonstrations across the country on February 22, referred to as the 22222 uprising.

“At present everything has become almost back to normal,” said U Win Thaw.

But “back to normal” seems like an exaggeration, given that branches remain closed and most customers still have no way to access large amounts of cash.

Bank officials were reluctant to discuss the shutdown on the record. U Than Lwin, a senior policy adviser at KBZ Bank, said banks were now able to trade foreign currency between themselves because the Central Bank had resumed the interbank foreign exchange market.

U Pe Myint, a senior adviser at CB Bank, the country’s third-largest by assets, said branches remained closed but banks “may” attempt to resume normal banking services if protests continue to remain small.

Several other sources in the banking industry confirmed that transactions had increased, but said it was mostly limited to large clients and seemed focused on the need to pay February salaries. It’s unclear whether this activity will persist in March, but there’s a sense that eventually the staff who have joined CDM will need to return to work.

“It’s very hard to predict right now but it should not be too long … at the end of the day, I have to eat and you have to eat,” said one bank official. “The longer it goes on though, the more I’m worried about the situation, both for the bank and for the economy.”

The next crisis looms

But what happens if and when banks are actually able to open their doors?

All indications are that they could be in for a very rough ride. Depositors are likely to pull out at least some of their cash when they get the chance, while the economic downturn will cause a rise in loan defaults, both of which will put pressure on the banks’ balance sheets.

Many of the local private banks were already in a shaky financial position from reckless lending during the Thein Sein government years, which led to high non-performing loan rates. This has been exacerbated by the effects of COVID-19, which have pushed more borrowers into default. Shortly after COVID-19 emerged, the National League for Democracy government was forced to relax deadlines for banks to get their loan books in order, pushing them out to mid-2023.

The banks have already got a taste of the reckoning that might be coming. When they reopened on February 2, the day after the coup, they were greeted by long lines of spooked depositors who were seeking to withdraw their cash.

Ironically, it seems that a rumour of impending demonetisation by the Central Bank, which it swiftly denied, actually helped the banks out, because it discouraged people from holding even more cash.

One financial institution has also tried – and failed – to stay open through the political crisis, apparently in an attempt to uphold the regime’s insistence, repeated regularly in state media, that “local banks are providing daily services”. Unsurprisingly, the one that did try to stay open was military-owned Myawaddy Bank.

Myawaddy is the sixth-largest private local bank by assets, with a market share of around 11pc. But after being inundated daily with long lines of customers seeking to withdraw their funds, the bank was forced to introduce a token system on February 16 to limit the number of customers at each branch, along with a K5 million cap on how much they could take out. Two days later the number of customers was cut to 100 day, and each was allowed to withdraw just K1 million. On February 23 it announced it was suspending withdrawals completely until early March.

When Frontier visited the branch at the corner of Bogyoke Aung San and Wardan streets in Yangon’s Lanmadaw Township on February 16, almost 500 people were lined up and trying to get their hands on tokens. Most appeared to be taking out the maximum K5 million.

“Some customers arrived here at 5am to withdraw cash,” said Daw Thida Oo, a 40-year-old North Dagon Township resident. “I arrived at 7am and managed to get token 168.”

State-run Myanma Economic Bank has faced similar difficulties in disbursing pensions from February 22 and was also forced to limit the amount that pensioners could withdraw.

Several banking industry sources said they thought it likely that the Central Bank would have no choice but to put in place limits on withdrawals and other measures in order to prevent banks from running out of cash when they reopen.

“This is a problem for every bank, not just Myawaddy … I think there will need to be some limitations,” said the senior official from a small private bank. “We will also need to collectively agree to reopen at the same time so we can try to manage this challenge together.”

On February 28, the Central Bank announced limits on cash withdrawals, effective from March 1. Individuals will be able to take out up to K2 million (US$1,420) a week, and organisations and businesses up to K20 million. ATM withdrawals have been capped at K500,000 a day. The announcement did not say when the restrictions would be lifted.

The Central Bank claimed implausibly that the limits were introduced to “facilitate the transition to digital economy” by reducing cash usage, rather than any concern about a looming run on financial institutions.

“Banks need to prioritise e-payments and electronic transfers for improving cash management of banks and non-bank financial institutions,” said the announcement, which was signed by new deputy governor Daw Than Than Swe and has not yet been posted online.

But the potential seriousness of the situation should not be underestimated. The last time Myanmar introduced such stringent withdrawal limits on the kyat was in February 2003, when the collapse of unregulated financial institutions led to a run on the private banks. The withdrawal limits only caused more panic; three major banks eventually collapsed, and the sector took about a decade to recover.

This suggests that Myanmar’s local private banks are likely to be facing a difficult few months even under the best-case scenario, and some banks may not survive. Branch closures and withdrawal limits will also continue to hinder businesses and limit individuals’ ability to access savings. But for protesters like Nwe Nwe Aye, that’s simply the price that must be paid to fight the regime.