Five years after the government liberalised Myanmar’s telecom sector, there is now fierce competition between four operators. That’s great for consumers, who enjoy the lowest data rates in Southeast Asia – but not so much for the companies that have invested in licence fees and infrastructure.

By KONRAD STAEHELIN | FRONTIER

OOREDOO provides “Myanmar’s fastest mobile network”, while Telenor owns “the nation’s largest network”. MPT wants to be “moving Myanmar forward” – a reference to it being state-owned and having a mandate to “drive development” and “unify Myanmar” – and newcomer Mytel wants to deliver the best service in order to win over customers.

The advertising slogans in Myanmar’s telecom sector are similar to what you would expect in countries where the market has matured over a period of decades, from large phones the size of suitcases to feature phones and SMS, and now smartphones and streaming.

Myanmar is entirely different. In a classic case of technological leapfrogging, it went from almost no phones to predominantly smartphones in a period of a few years. Since two new operators from overseas launched five years ago, Myanmar’s telecommunications sector has grown at a rate that once seemed impossible.

In 2010, a SIM card from the state-run monopoly Myanma Posts and Telecommunications (MPT) cost US$1,500. Today, MPT and its competitors sell them for $1, and the International Telecommunication Union puts SIM card penetration at 114 percent in 2018. Competition is fierce: 1GB of data is typically less than 70 US cents, making Myanmar one of the most affordable places for phone use in Asia.

Support more independent journalism like this. Sign up to be a Frontier member.

But to what extent have the companies that led the way in delivering cheaper SIMs and lower prices profited from this growth?

When Myanmar announced in 2012 it would open up one of the world’s final telecom frontiers, there was intense interest. Following a competitive and widely praised tender in 2013, Telenor from Norway and Ooredoo of Qatar were selected from a field of 12 bidders. They were promised milk and honey, a virgin market.

Now the gold rush is over.

There are two main reasons for this. First, the market has hit a certain saturation. “There are challenges of connecting those still unconnected, particularly poorer and rural communities,” said U Than Htun Aung, director of the Posts and Telecommunications Department, during the Myanmar Connect telecommunications conference in mid-September.

Second, the mid-2018 market entrance of Mytel increased competition. Mytel is a joint venture between Tatmadaw-backed Star High Public Co Ltd (28pc), local business consortium Myanmar National Telecom Holding Public Co Ltd (23pc) and Viettel (49pc), which is Vietnam’s largest mobile network operator and owned by the Vietnamese Ministry of Defence.

Put differently, the pie is not growing quickly anymore, and there are more companies fighting for a piece of it.

typeof=

Golden years, for some

Before 2018, business was good – at least for one of the two companies that won the licence tenders.

Telenor’s Myanmar operation was profitable from 2015, its second year. In some years it has reported profits of more than $200 million – almost half the $500 million it paid for its 15-year-licence to operate in Myanmar.

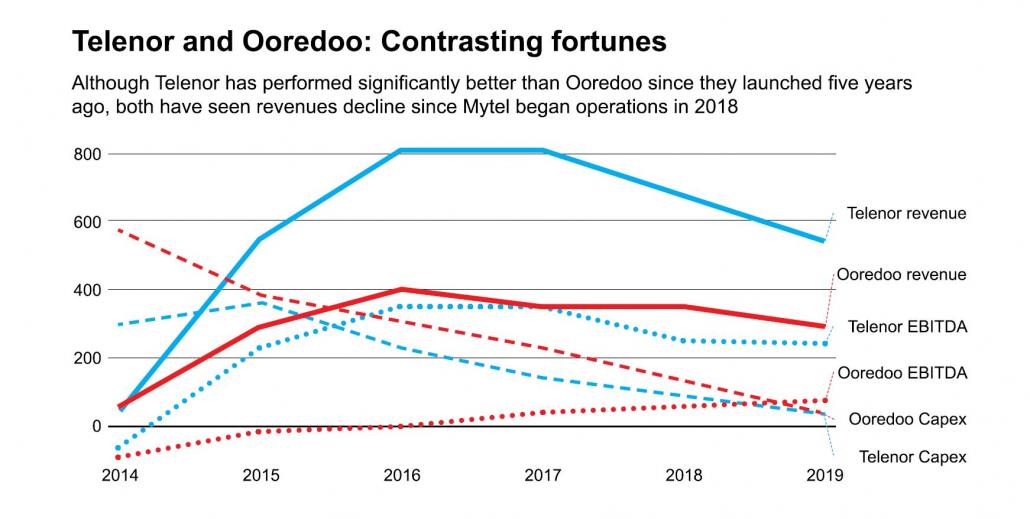

The industry’s most used metric when assessing financial success is called EBITDA, which stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation. It does not take into account capital expenditure, which is why Telenor could post positive EBITDA in 2015, despite investing $660 million in infrastructure over 2014 and 2015. But these early results made it a perfect start for Telenor’s Myanmar business. Despite both revenues and earnings shrinking visibly since Mytel’s market entry, Telenor’s first five years in Myanmar have been golden indeed. EBITDA margins have typically hovered around 40 percent of revenue.

It has not been quite the same story for Qatar-government-controlled Ooredoo. To begin with, it bid twice as much as Telenor for its licence, putting it $1 billion in the red from the start. Its capital expenditure was also 43pc higher than Telenor between 2014 and the first half of 2019, at more than $1.65 billion, corporate records show.

In Myanmar, the Qataris have faced an additional, but difficult to quantify, challenge: anti-Muslim sentiment.

Shortly before the launch of Ooredoo’s network operations in mid-2014, the Myanmar Times reported that in northern Shan State, the Lashio township committee for Ma Ba Tha, the Association for the Protection of Race and Religion, had issued a statement saying “that the group and all of its members will never answer a call from any group or any person using telecom company Ooredoo.”

On a similar note, The Irrawaddy quoted nationalist monk U Parmaukkha as saying: “The campaign is to protect the integrity of the Burmese nation and the religion because we doubt that we will have freedom when talking over their mobile network because the company is from an Islamic country.”

One official from a mobile phone tower construction company, who asked not to be named, said that “hunting for land to build Ooredoo towers was a nightmare, especially outside the main urban areas. They had a harder time than everybody else.”

It could have been worse, though. Unlike in many other countries, where every network provider builds its own network, tower sharing is common in Myanmar, helping Ooredoo to circumvent this discrimination.

There were two other factors that put Ooredoo behind. First, there was the crucial decision to ignore 2G and only build out a 3G network. In 2013, 2G did seem like outdated technology. But Telenor’s decision to install both 2G and 3G was ultimately vindicated, as it helped it to attract millions of rural customers whose lower spending power meant they could only afford 2G devices.

Second, Ooredoo relied heavily on expensive foreign experts. In contrast, Telenor invested in training local talent and drew on foreign talent from its regional operations, such as in Thailand, who already had experience in Southeast Asian markets.

This combination of factors has resulted in Ooredoo attracting only 11 million customers, barely half the number of Telenor (around 20 million). Moreover, Ooredoo has only posted positive earnings for the past two years, but at a comparatively low level. After four years of heavy losses, Ooredoo’s EBITDA margin hit 11pc in 2017 and rose to 16pc the following year. In the first half of 2019, it hit a respectable 25pc. So long the problem child for the Qatar headquarters, it finally looks as though Ooredoo’s Myanmar branch is growing up.

What changed for Ooredoo that helped to turn things around? It appears to have revised its business model and significantly reduced operating expenses. Management recognised the mistake of not implementing a 2G network and added it to existing infrastructure. The company is likely to become more profitable over the years, industry experts told Frontier.

Steve Tickner | Frontier

Mytel: a turning point?

These insights are available due to Telenor and Ooredoo being publicly listed companies, which requires them to publish financial reports.

This is very much not the case for the two other operators, MPT and Mytel. Approached for comment on their financial position, they did not have much to say.

As the incumbent operator with an established network of towers, MPT had a headstart when the market was liberalised. In 2014, it partnered up with two Japanese firms, telecom corporation KDDI and trading house Sumitomo, to prepare its operations for the new competition.

It seems to have worked: the Japanese introduced market-oriented principles to the company and a number of interviewees told Frontier that MPT was “doing well”, despite having to significantly shake up its pricing to stay competitive. MPT serves “over 23 million” customers, according to its webpage, although other recent figures from media reporting suggest it might be significantly more.

For Mytel, the newcomer backed by both the Myanmar and Vietnamese militaries, information is equally hard to come by. It has invested more than $1 billion in its infrastructure and paid $300 million for its licence – significantly less than Telenor ($500 million) and Ooredoo ($1 billion) paid for their licences. Within a year of its launch in February 2018 the company had attracted 5 million customers and aims to hit 10 million by early 2021.

When Telenor first became profitable in 2015, it had three times as many subscribers as Mytel and data prices were eight times higher. From this we can draw at least one conclusion: it is not possible that Mytel will be profitable this year, and it is highly unlikely that it will be in the near future.

A floor price on data set by the regulator, PTD, since June 2017 has made it difficult for Mytel to win over customers by undercutting existing players. Instead, it has resorted to some aggressive promotional tactics to gain a slice of the pie from MPT, Telenor and Ooredoo.

Right after its launch in June 2018, Mytel launched a lucky draw programme that was so easy to win that it was considered close to being a free service. PTD quickly stepped in and ordered it to stop the practice, citing competition rules that forbid services that are completely free.

In a similar case in March, PTD fined Mytel more than K300 million (about $200,000) after Mytel agents were found to have given out SIM cards for free. A Mytel spokesperson said the agents were not aware of the regulations. “They offered free SIM cards as they were so eager for sales. People already have SIM cards, and they wouldn’t buy them if we sold them, and thus we offered them [for free],” the spokesperson told The Irrawaddy in July.

Frontier emailed questions about Mytel’s aggressive strategy to all four operators but only Telenor responded, and it declined to comment on Mytel specifically.

But Mytel is not the only operator to run foul of the regulator. Since May, Telenor has received three warnings from PTD, while Ooredoo and Amara Communications, which operates internet service provider Ananda, have both received a single warning. Mytel has received three warnings in addition to its fine in March. Most of the warnings relate to violations of PTD’s Pricing and Tariff Regulatory Framework.

“Myanmar is a highly price-sensitive market,” said Mr Edwin Vanderbruggen, senior partner at legal advisory firm VDB Loi. “People don’t mind if the data speed is not as high as it could be – but they will switch operators immediately once they see that they can save money.”

One consequence of the increased competition will be downward pressure on revenues at the four operators. Both Telenor and Ooredoo experienced a decline in revenue in 2018, the year that Mytel launched, and are on track to record a further drop this year.

But looming on the horizon is 5G technology, which the telecom companies are already showcasing for marketing purposes. Rolling out 5G-capable infrastructure will be very expensive. MPT and Mytel appear to have enough financial backing from state sources to clear that hurdle, but it’s not clear whether Ooredoo and to a lesser extent Telenor would be able to make a profit on an investment in 5G before their 15-year licences end, given the competition and current size of the market.

Daw Nu Yin Myint, acting head of corporate communications at Telenor Myanmar, told Frontier that the company’s global strategy towards 5G was to transition gradually based on “use cases that are commercially viable”.

“Telenor Myanmar has one of the best 4G networks in Asia, and is well suited to support Myanmar’s digital development with the current network,” Nu Yin Myint said.

Rumours that both Telenor and Ooredoo are seeking to sell their operations have been floating around for years. In August, both operators were forced to deny widely circulated Facebook posts that claimed they “would pull out of Myanmar soon due to continuous losses”.

Even if the companies were in negotiations with potential buyers, reporting rules would generally not allow them to discuss the state of the talks. Several sources interviewed for this article repeated rumours that Ooredoo was on the lookout for a joint venture partner.

Telenor’s Nu Yin Myint insisted that the company still saw “enormous growth opportunities in digital content, streaming services, online gaming, e-commerce and more”.

“While growth in smartphone penetration has been rapid and there is now far greater access to mobile broadband, Myanmar’s digital journey has actually just begun.”